Imaginary Dinner Party, Part Two

By Lynn Crawford

Our climate is humid, but I keep my home airy and dry for the books. Now, walking to town, I breathe in the moist morning air, hoping it might nourish my skin, mood, and lungs.

Today’s first stop is the library, which has floor-to-ceiling windows with views of docks, ships, and the sea. That is where I first spot Karl, the man who becomes my builder. There he is on his boat, scrubbing its deck and readying fishing lines.

“Fishing is inherently optimistic,” he says, in one of our earliest conversations. It’s the same with reading and specifically mixing books, I think but don’t say.

Karl and I have separate interests (He, sailing, fishing, diving, cooking, music, and construction work. Me, books) but we do share a belief in effort. Even if it leads to failure. My list of failures is long (Karl’s is surely much shorter), but where would I be without them?

Not better off.

I sense quickly and assimilate (very) slowly. It takes time to identify something, and more time to absorb and even more to know what to do with it. The periods between those stages—sense, assimilate, implement—are difficult. So much can go wrong. But I stick with them rather than stare at the floor and nurse potential grievances.

This morning, our library, as usual, is populated with people browsing shelves, hunched at desks and tables reading journals and novels, school textbooks, sitting with eyes closed, or taking notes, writing letters, making lists, and staring out windows.

Sometimes I visit for the smell of so many books together or to look at people. I cannot stay long. In part because of the overstimulation, but mostly, because I never interact publicly with books. The thought of someone, anyone, watching me and a book together is upsetting. Written words make their way deep into all my open spaces and if I am anywhere near people, it means that they, too, can enter them.

I read alone at home.

But I do love our library. The clerks, the views, the new and old titles. The visitors, who nod and smile, stand outside for a smoke, sometimes mistaking me for a staffer and asking where the recent book section is and can I recommend a specific read for them or their friend or daughter (Yes, is always my answer).

I don’t read books at the library, but I do think about them, especially specific passages. This morning, at home, I copied down (wrote in my notebook) the one by Karl Marx used by Georges Perec at the end of his novel, Things:

“The means is as much part of the truth as the result. The quest for truth must itself be true; the true quest is the unfurling of a truth whose different parts combine in the result.”

This passage helps me understand “quest” as a holistic structure fusing a resolve with a goal, and relying on inter-functionality. A point running through Braiding Sweetgrass, whose author, Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer, writes, “We make a grave error if we try to separate individual wellbeing from the health of the whole.”

Armed with these words, I head down the library’s steep steps to visit builder Karl and show him the passage. I try only to visit him when I have something exciting to bring. When I get to his boat, I hand him the slip of paper with the words I handwrote.

He reads them, smiles. And explains that he is partial to Karl Marx and not just because they share a name (“though,” he says, “there’s something to that”) but because they both build. He builds boats, shelves, and docks from wood; the other Karl builds theories and systems from words and thoughts.

He then goes on to say, “I respect that books are your universe. But don’t forget that trees, water, and lands hold medicines too.”

I love my books and love means never letting your beloved down. But I did. I do. Because I get this far and am ready to quote the line, “Land holds many medicines,” before wondering how much I know about land. Any land. Including this land I’m living in. This land I’m living on.

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants

By Robin Wall Kimmerer

Milkweed Editions, 2013

Nonfiction

Botanist, professor, mother, scientist, activist, and enrolled member of Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer is the founding director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, whose mission is “to create programs that draw on the wisdom of both indigenous and scientific knowledge in support of our shared goals of environmental sustainability.”

Things: A Story of the Sixties

By Georges Perec

Grove Press, 1967

Translated from the French by Helen Lane

[Les choses, 1965, Éditions Julliard]

Novel

French novelist, filmmaker, documentarian, and essayist Georges Perec was known for his formally complex works that focus on ordinary, everyday minutiae that often go unnoticed. He was affiliated with the mainly French group of writers known as Oulipo, a “workshop of potential literature.”

Heal the People?

It starts with seeing.

–Robin Wall Kimmerer

You still haven’t looked at anything.

–Georges Perec

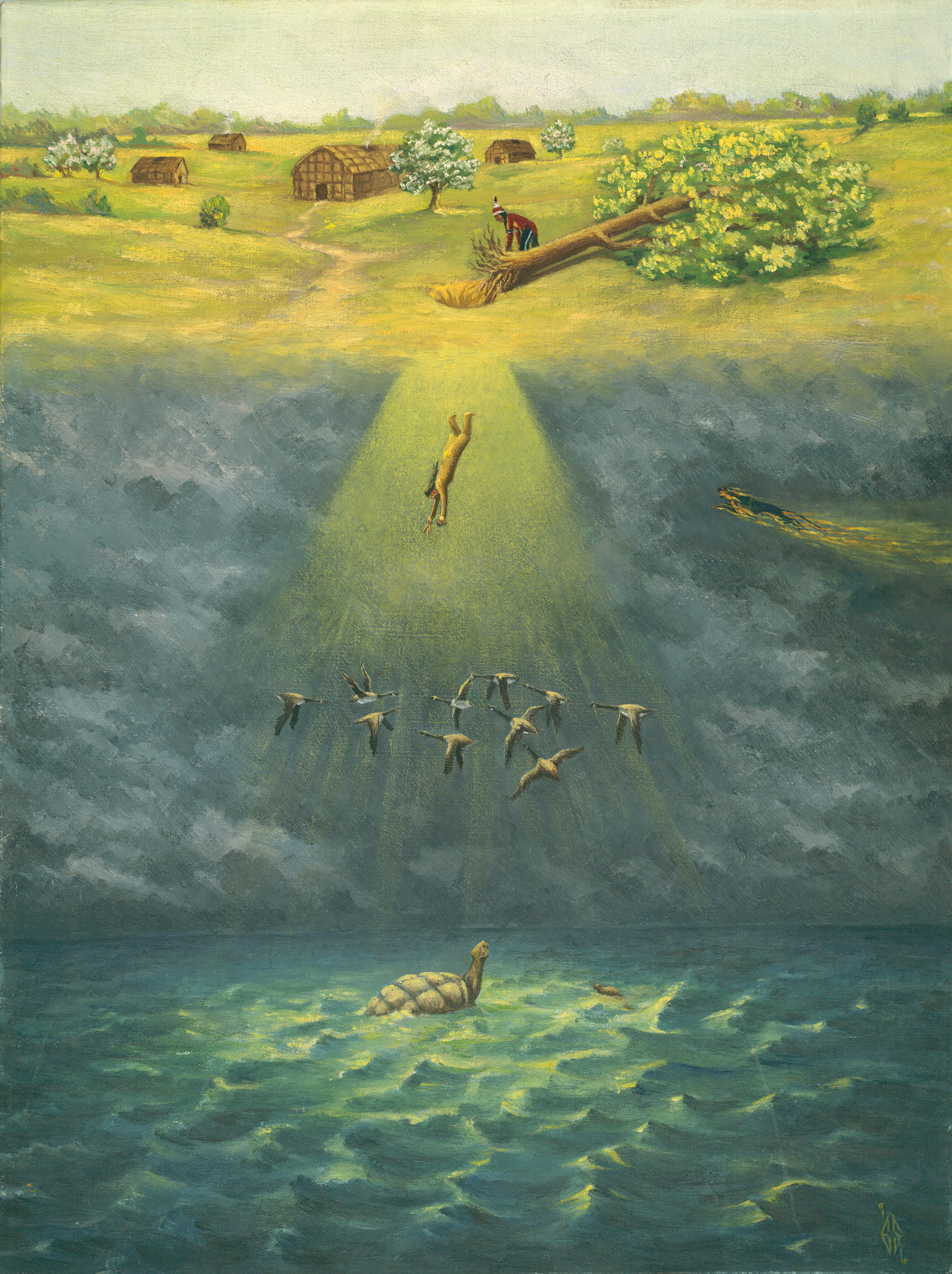

In her discussion of creation myths, Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer calls cosmologies a source of identity and orientation to the world. She addresses two origin stories, Skywoman Falling and Adam and Eve:

“On one side of the world were people whose relationship with the living world was shaped by Skywoman, who created a garden for the well-being of all. On the other side was another woman with a garden and a tree. But for tasting its fruit she was banished from the garden and the gates clanged shut behind her ... Same species, same earth, different stories.” Kimmerer imagines Skywoman saying to Eve, “Sister, you got the short end of the stick.”

Considering the books Braiding Sweetgrass and Things together illustrates modern expressions of the divergent tales. Skywoman is part of, and keeper of, earth’s elements. She gardens, attends, and nurtures. In contrast, Adam and Eve follow God, rather than the earth itself, and are banished for not doing so properly.

Physical structures (land, life, and objects) play important and divergent roles in each narrative. Kimmerer, with her background as a scientist and historian of indigenous lore, focuses on teaching and healing properties. She writes, “In the Western tradition there is a recognized hierarchy of beings with, of course, the humans on top—the pinnacle of evolution, the darling of Creation—and the plants at the bottom. But in Native ways of knowing, human people are often referred to as ‘the younger brothers of Creation’ … Plants know how to make food and medicine from light and water, and then give it away.”

Perec depicts the struggle his characters Jerome and Sylvie face accessing (unlocking?) potential. They have homes, friends, jobs, and each other, but lack strategies to navigate them—in part because they consume robotically, insatiably, and “the vastness of their desire paralyzed them.”

Nothing seems to be enough. In the same way glorious descriptions of heaven seem implausible, even for an afterlife, the bar (of excellence, achievement, being good?) is raised high. “Our citizenship is in heaven, and from it we await a Savior” reads a passage from the New Testament.

Which is why, when Perec writes (hilariously) that his characters “would become passionate about a suitcase—“one of those tiny, astonishingly flat cases in slightly grainy black leather”—you feel for them. A suitcase is something discrete and manageable, to acquire and hold onto. Their jobs, their leisure occupations, their relationship to one another and the “things” of the book’s title hold possibility, yet their forms of consumption bring no joy. “They wanted life’s enjoyment, but all around them enjoyment was equated with ownership.”

Perec convincingly portrays Jerome and Sylvie as striving for something but unable to identify what. He connects this, in part, to the fact that “They had no past, no tradition,” and the consumption that takes its place is unschooled, random, unmoored, and, like any addiction, unsatisfying. But the ghosts of the Adam and Eve story linger; the message, for example, If you do a, b and c, you will reach heaven. If you don’t do them, you won’t.

Kimmerer and the indigenous cultures she speaks of (and for) view objects and land as inherited gifts to sit and stay with. They have meanings and speak or otherwise transmit. That heritage is meant to be nourished, preserved, and passed on. She states, “Land and objects can hold many medicines. Land and objects offer healings.”

Braiding Sweetgrass sent me to other literature, including a wonderful piece by Anna V. Smith, “Heartland: The Yurok Tribe reclaims its ancestral territory in Northern California.” Frankie Joe Myers, Yurok Tribe vice chair, and Rosie Clayburn, Yurok Tribe and tribal heritage preservation officer, are quoted in the article, reminding us that indigenous cultures used and still use land for living, hunting and gathering, and ceremonial function.

Their land and water use are for sustenance, not to be bought and sold. Objects (things) are imbued with purpose. Clayburn states, “The tribe’s reclamation of land goes hand in hand with efforts to buy back cultural items from private collectors and repatriate objects from museums.”

As Smith writes, “Over the years, the tribe has reacquired hundreds of woven basket caps, condor feathers, funerary objects, ancestral remains, and traditional clothing like white deerskins and headdresses made of woodpecker feathers. So much of the Yurok identity—language, ceremony, food—is inseparable from the land they persist on.”

Woodpecker feathers carry weight, heart, and history. Valued for these functions, they mean more in an indigenous context than they do sitting isolated on a shelf in a private home or museum or antique stall collection. There is a fluidity between the physical objects and their origins, and between their past and present. Repatriation means returning them to their lands and people.

Both books make clear that objects can be gifts. And this is something Perec understands when he (again, with his trademark deadpan humor) writes that his characters “liked the visible signs of abundance of riches; they would have no truck with the slow process of elaboration which turns difficult raw material into dishes. It was all pâté, eggs in aspic and salads bought from the charcuterie.”

Jerome and Sylvie’s consumption saps their strength. Nothing they do is ever enough. Their frailty expresses itself in pursuing the very things that hinder them.

It’s easy to detect vestiges of the Adam and Eve narrative here. But there might be other ways to frame their quest. In an interview for The Review of Contemporary Fiction, Perec, discussing his novel, suggests a different approach: “Modern happiness is not an inner value. …It’s more like an almost technical relationship to your environment, to the world …”

Happiness has different meanings in the two myths and in the two books. Are there ways to rethink this? Modern happiness, for example—what is that and what can it be?

Imaginary Dinner Party is a literary series by Lynn Crawford that explores “what happens when books join forces.” Read the archive:

Part One, Under Stories (spring 2021)

Part Two, Heal the People (summer 2021)

Part Three, Think Like a Detective (fall 2021)

Part Four, Possession (winter 2022)

Part Five, Forms of Engagement (spring 2022)

Part Six, Conversations (summer 2022)

Part Seven (fall 2022)

Part Eight (winter 2023)

Part Nine (spring 2023)

Part Ten (summer 2023)

Part Eleven (winter 2023)

Lynn Crawford’s books include Simply Separate People (2002), Fortification Resort (2005), Shankus & Kitto: A Saga (2016), and Paula Regossy (2020). She is currently working on her next novel, Closely Touched Things. An excerpt from that book, Take Away From the Total, was published in issue no. one of Three Fold.

Part One, Under Stories (spring 2021)

Part Two, Heal the People (summer 2021)

Part Three, Think Like a Detective (fall 2021)

Part Four, Possession (winter 2022)

Part Five, Forms of Engagement (spring 2022)

Part Six, Conversations (summer 2022)

Part Seven (fall 2022)

Part Eight (winter 2023)

Part Nine (spring 2023)

Part Ten (summer 2023)

Part Eleven (winter 2023)

Lynn Crawford’s books include Simply Separate People (2002), Fortification Resort (2005), Shankus & Kitto: A Saga (2016), and Paula Regossy (2020). She is currently working on her next novel, Closely Touched Things. An excerpt from that book, Take Away From the Total, was published in issue no. one of Three Fold.

Fig. 1 Sky Woman, oil painting by Ernest Smith, Tonawanda Reservation, 1936. Ernest Smith (1907-1975) was a Tonawanda Seneca artist of the Heron Clan. From the collection of the Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, N.Y.

Read next: Issue no. three poetry section