Imaginary Dinner Party, Part Three

By Lynn Crawford

No single human, herb, building, tree, song, boat, bird, dream, cliff, or book contains everything. But selected combinations in the right amounts and at the right moments might.

Karl and I meet because he is a respected builder and I need a solid way to climb up to, and down from, my new home in the trees. Then I need book shelving. Then, because the shelves are floor-to-ceiling, I need rolling ladders with side rails and nonskid feet. From the start, Karl does exemplary woodwork and also seems interested in the slips of paper I bring him, with handwritten quotations of literary sentences.

Over time, we take walks, swim, go to movies, concerts, and community theater productions. We sail, visit museums, planetariums, and the town library. We have not—yet—been airborne, although our times together can feel like flight.

Karl measures, cuts, and sands wood for my shelving. He provides ladders. The two leading from the ground up into my home—one for the front entrance, another for the back—and several on rollers inside for access to shelved books.

I come to trust and rely on the functional equipment, and frequently visit Karl on his boat when it is docked, between excursions. There, he pores over nautical charts and attends to ship lines, sails, and deck. He brings in and selectively releases fish, monitors water surfaces, and scans the sky for weather and bird flight patterns.

We rarely exchange personal secrets. We do share our bodies and physical spaces (my home, his boat, our town, and its surrounding waters and land).

His presence makes me feel safe. With him I’m able to let terrible thoughts, always lurking nearby, in for a visit, rather than squash them down, block them out, or try to forcefully eject them. In Karl’s presence, I can let them seep in, settle, do their damage and, before too long, leave. Their limited stay is good enough healing for me. I try to be right there for Karl when he gets what I imagine are his own invasions.

As I said, we never fly but I do sometimes picture us on a jet: where we sit, how we sit, what we see, eat, read, drink, and listen to. What happens when the plane dissolves, leaving us aerial, unprotected, embracing, rolling, and soaring through clouds.

I come to love and rely on Karl and his boat whether we are far away from land or anchored in the marina. I say marina but there are only three boats there and one belongs to him. Our time together feels medicinal and, to quote another Karl (Marx): “Medicine heals doubts as well as diseases.”

That is an example of a written-down sentence I bring to “my” Karl on a slip of paper.

Doubts might ward off failure but they also stunt growth. Growth comes from failure, or can come from it.

Progress is not victory-dependent.

These are the kinds of things I sense but never discuss with Karl. In the same way I might never know why he throws some fish back and keeps others, or what he sees coming behind us out at sea that makes him turn his boat quickly and head back to the marina after asking me to go below deck, or what brings him to this town or who built his boat or what he gleans from the sea.

I love us, together, looking at the water and sky, picturing myself as a medical researcher or pianist or chef. But not for long. Because, ultimately, nothing makes me happier than being back home with my books, neatly alphabetized on their floor-to-ceiling shelves. Spending long hours examining them and imagining how they were written, built, and bound.

Pretending to be, or be with, figures within them: Nefertiti, Penelope, Ophelia, Cleopatra, Antigone, Skywoman. Books hold medicines. I know, and believe, lands hold them too. It is an awkward personal topic.

Wanting to learn about land, I made but never realized plans to study atlases, take treks, deep sea dive, and camp. Dig, gather, and analyze soil samples. Compile information on index cards, possibly stringing some together and transferring the information, longhand, in specific notebooks.

None of that ever happened. The project was too grand, messy, daunting.

For me, personally.

I was ashamed never to have even attempted it.

But then I found some guidance in words from a human named Tomson Highway.

“English is so hierarchical. In Cree, we don’t have animate-inanimate comparisons between things. Animals have souls that are equal to ours. Rocks have souls, trees have souls. Trees are ‘who,’ not ‘what.’”

That was all I needed to properly realign.

Earth as a who. Earth is a who. That is a way I can approach it.

I thought, wrongly, that compiling Earth information would be the respectful, thorough, ultimate way to connect, even while sensing it would not lead to the exchange I was looking for, in part because it was so forced, artificial.

For me, personally.

There are, of course, places for that.

I had no idea that what I wanted (not true, I knew but could not say what I wanted)—was connection to Earth and to talk. For Earth and I to talk.

Thank you, Tomson Highway. Thank you for your words, thank you for showing that invaluable information can be contained within an exchange or within a single sentence. Or two.

Braiding

Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of

Plants

By Robin Wall Kimmerer

Milkweed Editions, 2013

Nonfiction

Botanist, professor, mother, scientist, activist, and enrolled member of Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer is the founding director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, whose mission is “to create programs that draw on the wisdom of both indigenous and scientific knowledge in support of our shared goals of environmental sustainability.”

By Robin Wall Kimmerer

Milkweed Editions, 2013

Nonfiction

Botanist, professor, mother, scientist, activist, and enrolled member of Citizen Potawatomi Nation, Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer is the founding director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, whose mission is “to create programs that draw on the wisdom of both indigenous and scientific knowledge in support of our shared goals of environmental sustainability.”

Things: A Story of the

Sixties

By Georges Perec

Grove Press, 1967

Translated from the French by Helen Lane

[Les choses, 1965, Éditions Julliard]

Novel

French novelist, filmmaker, documentarian, and essayist Georges Perec was known for his formally complex works that focus on ordinary, everyday minutiae that often go unnoticed. He was affiliated with the mainly French group of writers known as Oulipo, a “workshop of potential literature.”

By Georges Perec

Grove Press, 1967

Translated from the French by Helen Lane

[Les choses, 1965, Éditions Julliard]

Novel

French novelist, filmmaker, documentarian, and essayist Georges Perec was known for his formally complex works that focus on ordinary, everyday minutiae that often go unnoticed. He was affiliated with the mainly French group of writers known as Oulipo, a “workshop of potential literature.”

Think Like a Detective

Cautionary stories of the consequences of taking too much are ubiquitous in Native cultures, but it's hard to recall a single one in English.

–Robin Wall Kimmerer

The trouble with market researching is that it cannot go on forever.

–Georges Perec

In Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer defines Honorable Harvest as, “the Indigenous canon of principles and practices that govern the exchange of life for life.” This system plays a key role in Braiding Sweetgrass. In the novel Things: A Story of the Sixties, Georges Perec illustrates the damage caused when the principles are neglected or abused.

Braiding Sweetgrass is filled with spiritual and functional reciprocities between wind, animals, rivers, herbs, rocks, humans, and tree clusters. People fit into, are not superior within, this structure. Or as Kimmerer puts it, “The story of our relationship to the earth is written more truthfully on the land than on the page.”

What the author finds most extreme in the story of Eve’s banishment from the Garden is its resulting destruction of human-earth connection. “Look at the legacy of poor Eve’s exile from Eden: … It’s not just land that is broken, but more importantly our relationship to land.”

Perec’s novel is set in 1960s Paris, during the rise of capitalism and its accompanying consumer culture. His characters Jerome and Sylvie personify what Kimmerer describes as being “caught in a trap of overconsumption, which is as destructive to ourselves as to those we consume.”

Jerome and Sylvie, driven by some powerful, lurking engine that demands focus on themselves, or at least their path, or else risk falling off, being left behind and never recovering. The condition leaves them swamped, lost, and numb: “They possessed, alas, but a single passion, the passion for a higher standard of living, and it exhausted them.”

Their exhaustion is not from a long or difficult labors, whose end brings relief. Rather, they live in a 24-hour cycle devoted to pursuing their “passion” despite the unsatisfying results their expenditures generate. Days are full but nothing really seems to ever happen.

Much of Braiding Sweetgrass stresses the value of assembled healing rituals. “Ceremony focuses attention so that attention becomes intention. If you stand together and profess a thing before your community, it holds you accountable. … These acts of reverence are powerfully pragmatic. These are ceremonies that magnify life.”

While the world portrayed in Things contains bleak vacancies, the language (the rhythm and sense of anticipation) Perec employs wields powers. It strategically shifts between calm, comic, dull, sweet, sinister.

The opening passage describing the couple’s apartment could easily be an opening scene in a horror film. Something wicked comes, but what, from where, and how soon?

“Your eye, first, would glide over the grey fitted carpet in the narrow, long and high-ceilinged corridor. Its walls would be cupboards, in light-coloured wood, with fittings of gleaming brass. Three prints depicting, respectively, the Derby winner Thunderbird, a paddle-steamer named Ville-de-Montereau, and a Stephenson locomotive, would lead to a leather curtain hanging on thick, black, grainy wooden rings which would slide back at the merest touch. There the carpet would give way to an almost yellow woodblock floor, partly covered by three faded rugs.”

Nothing damaging or even remarkable is named but it is the kind of slightly off, suspenseful tone that leads to disaster.

The passage continues, “It would be a living room about 23 feet long by 10 feet wide. On the left, in a kind of recess, there would be a large sofa upholstered in worn black leather, with pale cherrywood bookcases on either side, heaped with books in untidy piles.”

The extended sense of menace prepares the stage, any moment, for a masked ax wielder to drop down from the ceiling or creep out of a corner. Perec conjures a convincing lurking force that is impossible to locate or pin down.

Kimmerer conveys the ways thoughtless consumption damages and is impractical. She voices concern for humans even as we harm the planet and therefore ourselves and one another. This happens in part because we have a blind spot as to what planet Earth even is, and are too focused on momentum to take time to be curious.

Interdependency is fundamental to Honorable Harvest. Braiding Sweetgrass again and again details Kimmerer’s premise that what affects one of us affects all of us. “Us” meaning all life forms: humans, bushes, deer, wind patterns, rocks, fish (and so on—all life forms).

This is particularly true for land and ancestors, both of which should be honored, regardless of their performance. Honor functions as a kind of structuring principle, not a reward for “good” deeds or behavior. That lands and ancestors came into existence is reason enough.

Kimmerer writes, “Indigenous peoples’ responses to injustice has historically been through honoring land and lives in and on it and ancestral connection.”

There are countless stories exemplifying this, including a recent one in Indian Country Today:

The family of 17-year old runner Ku Stevens, Yerington Paiute Tribe, organized a “Remembrance Run” to honor those, including his own great-grandfather, who were forced into boarding schools. Stevens retraced the route his great-grandfather, Frank Quinn, ran in 1913, at age 8, to escape the school. He attempted it three times before he succeeded. Stevens ran in the day but acknowledged his grandfather’s escape must have happened at night.

At the end, Ku felt his people and his ancestors at his feet. “That’s family, you know, you’d do anything for them,” he said. (Indian Country Today)

In all of Things there is no mention of a relative, close friend, childhood memory, holiday, or family meal.

Good citizenship, so crucial for the planet and all of the lives in and on it, has not been introduced to them. They suffer. Adding to the dis-ease is the fact the powerful strain occupying them is intangible—it does not appear as a single law or decision or result of war or even a strategic gap his characters face but as things that just happen, therefore seem unstoppable. The force cannot be harnessed because it cannot be precisely identified.

Consider the following passage, from Perec’s book, Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, from 1974:

“We don’t think enough about staircases. Nothing was more beautiful in old houses than the staircases. Nothing is uglier, colder, more hostile, meaner, in today’s apartment buildings.”

The combination of care, disappointment, and anger expressed in the passage seems displaced, which makes the writing poignant and sad.

The staircase is mean, but where does the sentiment come from, where else might it be directed?

Jerome and Sylvie’s world lacks the grounding logic of communal living and as a result the characters are not invested in the world, its residents, themselves, or one another. It is unclear what replaces that except a vague kind of quest that Perec depicts as a disconnect generating more vacancies.

In a 1980 interview in Review of Contemporary Fiction, Perec states, “Things is the story of poverty inextricably tangled up with the image of wealth.”

The principles of Honorable Harvest are hard to beat as a remedy for this ailment. Its premise is fundamental: We’re all better when we are tending, and tended to.

Imaginary Dinner Party is a literary series by Lynn Crawford that explores “what happens when books join forces.” Read the archive:

Part One, Under Stories (spring 2021)

Part Two, Heal the People (summer 2021)

Part Three, Think Like a Detective (fall 2021)

Part Four, Possession (winter 2022)

Part Five, Forms of Engagement (spring 2022)

Part Six, Conversations (summer 2022)

Part Seven (fall 2022)

Part Eight (winter 2023)

Part Nine (spring 2023)

Part Ten (summer 2023)

Part Eleven (winter 2023)

Lynn Crawford’s books include Simply Separate People (2002), Fortification Resort (2005), Shankus & Kitto: A Saga (2016), and Paula Regossy (2020). She is currently working on her next novel, Closely Touched Things. An excerpt from that book, Take Away From the Total, was published in issue no. one of Three Fold.

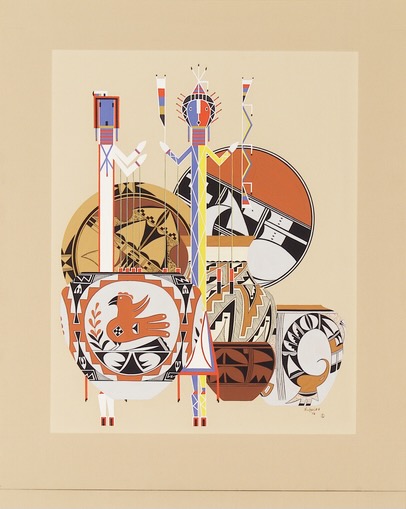

Fig. 2 Daniel D. Nicholas, detail of Still Life, 1978, matboard, gouache/opaque watercolors, 50.6 x 40.5 cm. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (25/8468)Part One, Under Stories (spring 2021)

Part Two, Heal the People (summer 2021)

Part Three, Think Like a Detective (fall 2021)

Part Four, Possession (winter 2022)

Part Five, Forms of Engagement (spring 2022)

Part Six, Conversations (summer 2022)

Part Seven (fall 2022)

Part Eight (winter 2023)

Part Nine (spring 2023)

Part Ten (summer 2023)

Part Eleven (winter 2023)

Lynn Crawford’s books include Simply Separate People (2002), Fortification Resort (2005), Shankus & Kitto: A Saga (2016), and Paula Regossy (2020). She is currently working on her next novel, Closely Touched Things. An excerpt from that book, Take Away From the Total, was published in issue no. one of Three Fold.

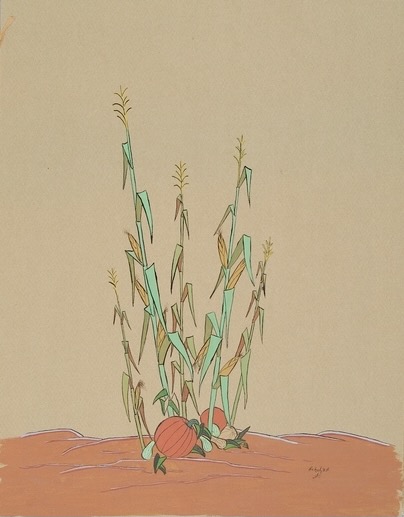

Fig. 1 Daniel D. Nicholas (Oneida/Cree), detail of Harvest, 1969, paperboard, ink, gouache/opaque watercolors, 50.8 x 40.5 cm. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (25/9450)

Read next: Spoken word by Akinyemi Sa Ra