Imaginary Dinner Party, Part Eleven

By Lynn Crawford

The lost glove is happy.

–Vladimir Nabokov

Sensitivity requires discipline.

–Nathalie Sarraute

When reading in public I sit straight, feet to the ground, book at eye-level. When home, or on Karl’s boat, I sit on a pillow or cushion, knees to my chest, head forward. Or legs crossed, spine curled—fetal postures ...

–Imaginary Dinner Party, Part Nine

“Excuse me,” says Robert, our visiting aquatic researcher, speaking from the town hall podium, raising an index finger while sipping from the water flask harnessed across his chest. “Dehydration leaves me off-kilter, which reminds me to remind you that fluids are essential for balance. I, as you see, can self-replenish. Not the case with our planet, which, because of excessive water pumped out of it, is parched and therefore physically askew.”

He continues his speech, providing a general update on his team’s investigation into the surprisingly healthy condition of the ocean at our town’s edge, ending with a rousing fist pump while declaring, “As my brother Leonard says, ‘There are heroes in the seaweed!’”1

The audience claps, someone chants: “Gloves, Gloves, Gloves,” others join in, Robert smiles, his wife meets him at the podium. Holding hands they bow, shout “GRATITUDE!” and sprint to the bikes they will ride to the station before boarding the train that will take them away.

Earlier that morning, home after trapeze practice with Rose, I replenish (fruit, cashews, still water), then wash and dry my hands before gingerly thumbing through an unsigned personal journal comprised of words, clippings, and intricate sketches I came across in the library stacks Found Material section. I’ve had, and neglected, this document for weeks and it’s due to return. Yes, I could renew, but try to utilize each borrowed item within the original lending timeframe for a blend of personal discipline and community consideration.

This document is an intriguing read. It’s a compilation of handwritten notes, some on notebook pages, others on scraps of paper, discovered in a large, rambling estate when relatives and realtors cleared out its main home, guest house, and barn.

I peruse, rather than closely examine, these kinds of unofficial documents, or what I sometimes call makings, only because I am unsure if I am a welcome guest or a prowler.

Thinking again of the thriving seabed in waters bordering our town, I wonder if any pages of words or drawings were dumped into this part of the ocean and, if a lost glove can be happy, can a lost manuscript be happy too. I regret that line of inquiry but then appreciate where it takes me: Not all expression is meant, or made for, exchange.

Later that day I return to the library, just as Rose, in a billowy white blouse tucked into a billiard-green pencil skirt, glides down the staircase from her office to the main lobby. Seeing me she waves, smiles, heads to the front desk, where she chats with staff before walking toward the book stacks.

On the way there myself I pass a mother and daughter I easily recognize as regular library visitors. They stand close, heads bent together.

“Ah, here it is,” says the mother, removing a volume from its slot, “This book is the first in a wonderful mystery series featuring a villain-turned-psychologist-turned-ace detective, who inspires awe, tenderness, and suspicion.” She cradles the volume close to her chest as they walk to the checkout desk but stops when she sees me and says, “Hello there, might I ask a quick question?”

I smile and nod.

“We see you here in the library often and notice that you tend to sit straight, feet to the ground, book at eye-level. Do you read that way at home too?”

“Never,” I answer.

She smiles, and says, “I didn’t think so.” She reaches out, shakes my hand, puts her arm around her daughter’s shoulders as they walk to the checkout desk. The exchange fills me with gratitude which I let myself bask in for a moment.

I feel a pat on my back. It is Rose, saying she looks forward to the book discussion and could I come a bit early to “help set a tone.”

“Of course,” is my answer.

A small group of volunteers unfold chairs and place them around a table for the presentation, which begins with a passage from the Marguerite Duras novel, Sailor from Gibraltar:

One’s always more or less looking for something to arise in the world and come toward you. Whether that’s a lost love or a reason not to go home again ... 2

These words are so beautiful and (I think?) specifically human and help to explain why I respect but do not love book group. For me, personally, reading is—well, can be—risky, stripping me down to bones, nerves, and tendons. Group chatter, however well intentioned, triggers (can trigger?) uncontrolled circulation of thoughts, feelings, and possibilities that are then dispersed somewhere in space, immature, free-floating, unprotected and may never return.

The Duras line wields a form of power that demands incubation before I can think of, let alone, absorb, let alone say anything about it. Even a casual public discussion might shatter all that I’ve tried so hard to gather, organize, build, incubate, and then, at the right moment—discuss.

This helps explain why I live in my house, filled with floor-to-ceiling books and mobile ladders, at the edge of town, high up in the trees. My home, along with Karl’s boat, the library stacks, and Rose’s top floor office with trapezes and a panoramic view, allow me a degree of safety. Should I blunder in one of those spaces (for example, mistakenly verbalize a misguided, even damaging, thought or feeling I have toward a human, tree, or book) I panic, dissolve, and self-isolate before generating more harm. But without safeguards I might do just that. Generate even more harm. Not intentionally, but because of the limited tools I have access to.

This is an assessment.

There, I wrote it.

Not gladly.

Truthfully (for

now) but

not gladly.

Not gladly at all.

Underland: A Deep Time Journey

By Robert Macfarlane

W. W. Norton & Company, 2019

Nonfiction

Robert Macfarlane’s books include Mountains of the Mind, The Old Ways, Landmarks, and, with Jackie Morris, The Lost Words. He lives in Cambridge, England, where he is a Fellow of the University of Cambridge.

By Robert Macfarlane

W. W. Norton & Company, 2019

Nonfiction

Robert Macfarlane’s books include Mountains of the Mind, The Old Ways, Landmarks, and, with Jackie Morris, The Lost Words. He lives in Cambridge, England, where he is a Fellow of the University of Cambridge.

Species of Spaces and Other Pieces

By Georges Perec

Edited and translated by John Sturrock

Penguin Books Ltd, 1998

Nonfiction

French novelist, filmmaker, documentarian, and essayist Georges Perec was known for his formally complex works that focus on ordinary, everyday minutiae that often go unnoticed. He was affiliated with the mainly French group of writers known as Oulipo, a “workshop of potential literature.”

By Georges Perec

Edited and translated by John Sturrock

Penguin Books Ltd, 1998

Nonfiction

French novelist, filmmaker, documentarian, and essayist Georges Perec was known for his formally complex works that focus on ordinary, everyday minutiae that often go unnoticed. He was affiliated with the mainly French group of writers known as Oulipo, a “workshop of potential literature.”

The void migrates to the surface

–Advances in Geophysics, vol. 57, edited by Lars Nielson,

as referenced in Underland: A Deep Time Journey by Robert Macfarlane

The subject of this book is not the void exactly, but rather what there is round about or inside it.

–Georges Perec, Species and Spaces, translated by John Sturrock

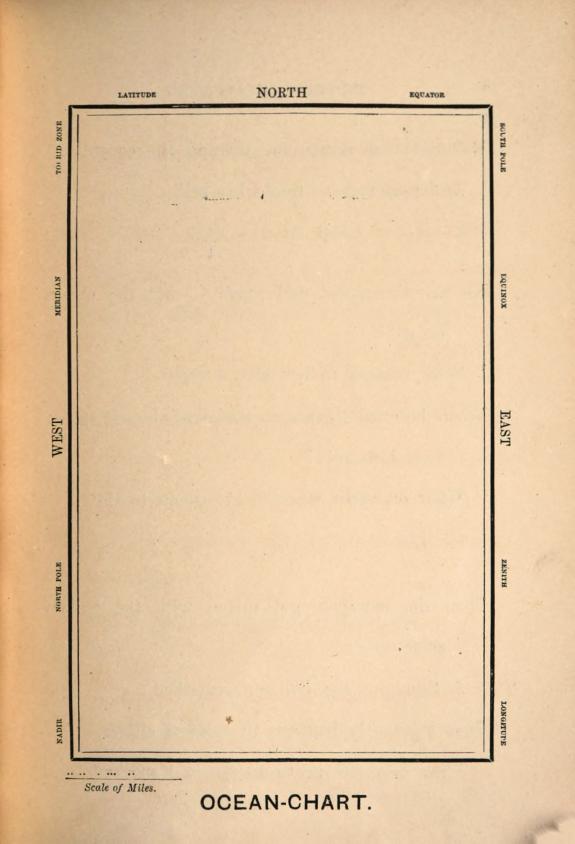

Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark: An Agony, In Eight Fits (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1876), illustrated by Henry Holly.

Endnotes

1. Leonard Cohen, “Suzanne,” Songs of Leonard Cohen, 1967.

2. Marguerite Duras, The Sailor from Gibraltar, translated by Barbara Bray (New York: Grove Press, 1952).

Imaginary Dinner Party is a literary series by Lynn Crawford that explores “what happens when books join forces.” Read the archive:

Part One, Under Stories (spring 2021)

Part Two, Heal the People (summer 2021)

Part Three, Think Like a Detective (fall 2021)

Part Four, Possession (winter 2022)

Part Five, Forms of Engagement (spring 2022)

Part Six, Conversations (summer 2022)

Part Seven (fall 2022)

Part Eight (winter 2023)

Part Nine (spring 2023)

Part Ten (summer 2023)

Lynn Crawford’s books include Simply Separate People (2002), Fortification Resort (2005), Shankus & Kitto: A Saga (2016), and Paula Regossy (2020). She is currently working on her next novel, Closely Touched Things. An excerpt from that book, Take Away From the Total, was published in issue no. one of Three Fold.

Read next: Issue no. twelve poetry section