Gilbert and Lila Silverman

By Cary Loren

Art patrons Gilbert and Lila Silverman enjoyed the affordability and irreverence of collecting Fluxus and Conceptual art. Detroit art offered a similar attraction—it was abundant and low-cost. The Silvermans’ business was in real estate investing and building. They studied the artists in the region, and recognized Cay Bahnmiller’s interest in landscape at her landmark exhibition at Feigenson Gallery in 1980, “Transportation = Transformation = Translation + Land According to Use.”

In a review of Bahnmiller’s show for Artspace magazine, Karen Roth wrote, “Notebooks sit on the shelves—thick, textural, tactile books recording observations. Notebooks for the viewer to study. Detroit is transformed. It becomes universal, explored and recorded by Bahnmiller and in turn by the viewer. She goes beyond any obvious content which man/woman created and reveals the magic of the site. It’s an exciting show.”1

As the Silvermans acquired several pieces from the Feigenson Gallery, they grew closer to Bahnmiller, often buying work directly from the artist. One such purchase was a notebook on the landscape project. This small binder included preliminary sketches, notes, and slide photographs and was assembled after the fact, possibly at the Silverman’s request. Notes from a statement at the center of the binder describe Bahnmiller’s system of coded symbols to describe the city:

1. using known system, a-z, with arrows, etc., such as a sign, or code network quick and compartmentalized driving on the freeway, the sign repeats the fact. Exit “x” —>. and the ramp. 2. Rationalization of opposition what “h” means..? 2 x 2 = 4 rules of math / assumptions of numbers accepted, that set defined. Explanation tools and toolbox uses / the invention of other possible, “imagined” uses / same equivalent. 3. a-z is known. applicable to a quick note-hand of logistics and content of objects and arrangement of a particular space. 4. Could be further “outlined” categorized of subdivided numbers / the alphabet grammar applied to geometry of space. Languaged part of process of spectator / participant and Other-Object / “language as organic fact of objects” not to be confused language / not as a linguistic science. In part or as constant with change of the equipment. / Rules / Requirements / Basics of landscape composition, slant / curve / transport system, vehicles within area / cloud cover - % direction, athletic area, bldg unused space, mythology of place, construction of “sentence” possible? XXXX a plus b or c minus a / parts within a + b = the whole in constant rearrangement 11/26/822

Bahnmiller and the Silvermans shared a fascination with public spaces. In reference to a potential collaboration, the artist made color swatches and suggestions for painting an urban community center a “mediterranean blue” in Detroit.

“Thank you for asking me my opinion in the matter; there is nothing that interests me more probably than urban spaces and use,” Bahnmiller wrote to Gil Silverman.3

She was one of six artists featured in the exhibition Gil Silverman Selects, shown in 1981 at the nonprofit Detroit Focus Gallery. (Other artists included David Barr, Charles McGee, Keith Rennie-Johnson, Lester Johnson, and Jim Duffy.) In the exhibition catalogue, Silverman wrote, “I’ve talked to her [Cay Bahnmiller] a lot and I still don’t understand—but then I wouldn’t have understood Einstein either.”4 The Silvermans continued adding her work to their collection over the next 20 years. Outside of Fluxus, Bahnmiller enjoyed the most comprehensive representation.

The Silvermans’ daughter Wendy recalls that she once came home to find her father hanging a large wall entirely with Bahnmiller’s paintings. “‘Wow!’ I said to my father, ‘You certainly have a lot of Cay’s paintings,’ and my father said, ‘Yeah, I think she’s the most important artist in the city,’ and he repeated that to me many times ... Cay worked at Peter’s Palate Pleaser at Long Lake Road and Telegraph, and she’d always be at the house catering and serving guests food, and that’s how I met her. She was a little caustic with me at first. She’d say, ‘Ack! those shoes!’ and point at my shoes. ‘It looks like you spent a lot of money on them. Why don’t you spend money on art instead?’ That was her personality.”5

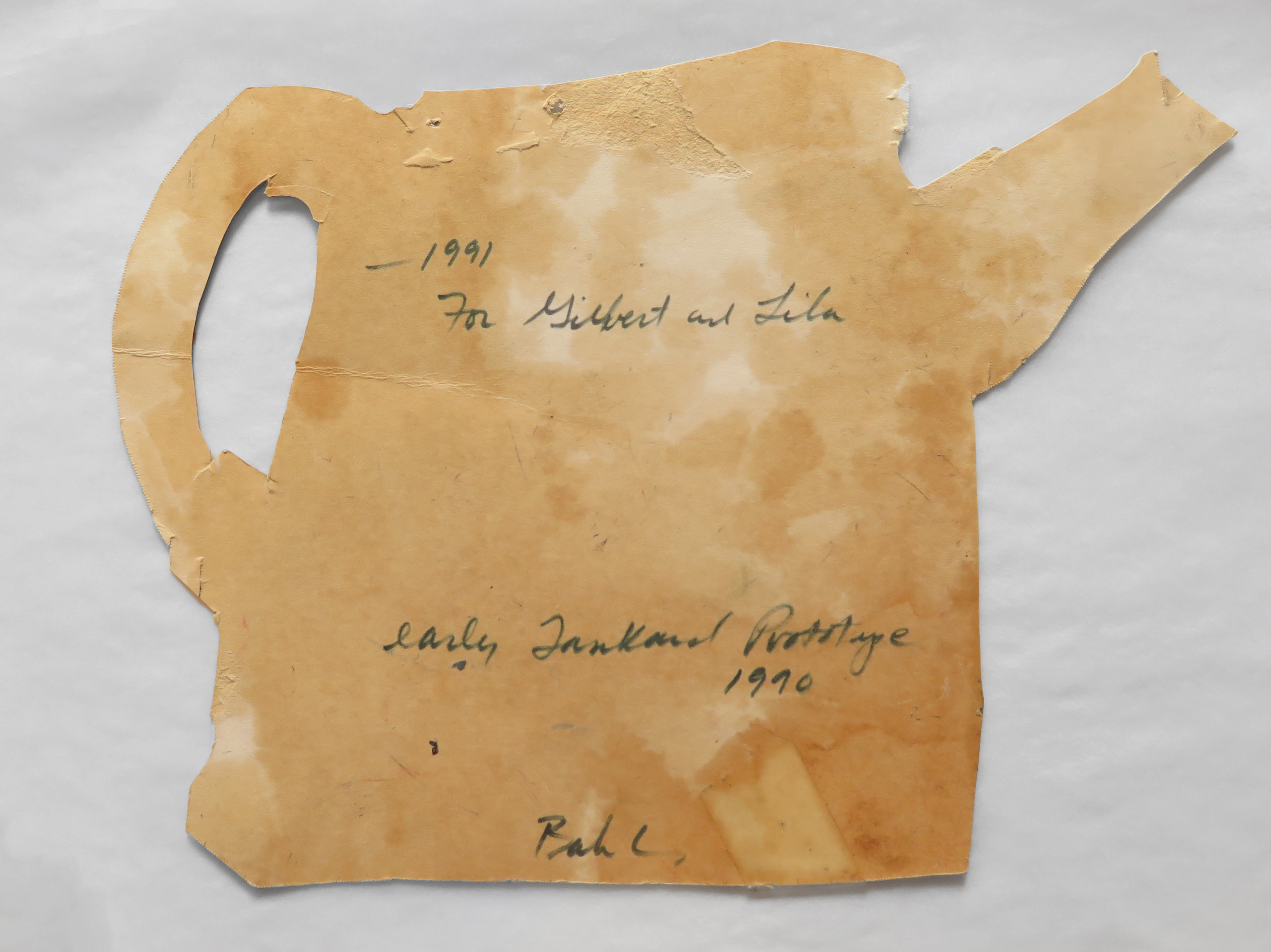

Between 1979 and 1994, Bahnmiller worked on a series of unusual object paintings based on photographs she found in 1930s and 1940s auction catalogues. The series included antique English tankards, tea kettles, regency chairs, and other 18th and 19th-century domestic objects. Bahnmiller enlarged each piece, drawn in perspective, and carefully cut them along their outline. Negative space was cut away and left open to give the realistic look of the actual object. A few were displayed in a 1990 exhibition at Susanne Hilberry Gallery.

The Silvermans bought four object paintings from the Hilberry gallery in 1991: a pitcher, tankard, tea kettle and basket, appreciating their humor and conceptual ties to Fluxus. They were made to be hung from period-specific iron nails that Bahnmiller scavenged from 19th-century picture frames. Following the purchase, Bahnmiller sent the collectors a note: “Dear Gil, Enclosed are the actual nails from paintings that are ideal for hanging the pitcher and tankard—very similar to those used during construction. You are the first person I’ve ever given any of these to!”6

A month later, Bahnmiller mailed another letter, along with the original prototype for the series, as a gift:

[May 7, 1991] Dear Gil and Lila, I just came across the first tankard prototype I made; before the tankard and pitcher you have were developed. I want you to have this with my warmest regards. Those two early cut-outs—I have a very strong feeling that they are pivotal in the progression of my work, especially to the ongoing project. Thank you for your generous support and belief in my work and for your courageous vision. I was proud of you both last Wednesday night. Forgive my sentiment. Best, Cay

The underpinning for this body of work—and much of her other art—was the concept of afterlife of antiquity, a near-anthropologic approach in art that had become resurgent through the studies of Aby Warburg and the Frankfurt school. Recognizing the symbolism and migration of art through time, Bahnmiller situated her work within this dialogic framework. In an artist statement from 1993, she wrote about being drawn toward philosopher Theodor Adorno’s idea of the negative dialectic and her attraction to historic artifacts:

“The stagecoaches, tankards and chattel of life in the 1800s rewrite historical elements that are a condensation of memory and satire. Boswell’s London Journals 1762, documentation of costume, and the present re-emergence of the sensibility of a prairie geography in Detroit, where an inversion of Nature tunnels through abandoned spaces, results in the color and shape of a fragmented, temporal sequence. The stagecoaches are emblematic cycles of history, imaging designated passage. Tankards are also repositories of the displaced ecclesiastical of everyday life.

Found objects are often embedded within the paintings. Bits of copper, iron, wood, a pearl earring, and china cups compose “Esther,” a collaged painting, 1992. Pieces of Spode recall Dickinson’s poetics—“Our Life—His Porcelain / Like a Cup / Discarded of the Housewife / Quaint—or Broke / A newer Sevres pleases / Old ones Crack.” Dickinson was one of the earliest to embody the negative dialectics that Adorno much later went on to explicate. Often my method of painting, where paint is applied and negated, excavated, resembles a similar poetic. […] I wanted to express the possibility of an actual curvature in painting, as if through paint I could transpose and model porcelain, and restore the creation of a personal heraldry, of insignia and imprint.”7

Bahnmiller wrote in gratitude, “Dear Gil and Lila, Enclosed is the receipt of our transaction, and a set of regency chairs. I am very pleased that you have this part of the project in your collection especially that bucket. Thanks again ever so much.”8 Bahnmiller stayed in touch with patrons and often paid them special attention by offering critical insight into her work and gifting handmade booklets, sketches, and other material related to the art, although such close relationships could also occasionally be constraining and forceful, leading to alienation and regret.

A few years later, she mailed a seven-page staple-bound artist book to the Silvermans.9 The front cover features a small stagecoach watercolor and, on the rear is a page from The Herb Companion, a bi-monthly mail-order catalogue “in celebration of the useful plants.” The book consists of several typed poems, one to a page. Such titles as “Tankard,” “Columbine,” “Charger,” “Coach,” and “Bandbox,” reference, in her words:

“the labile nightmare that accompanies every painting.” And from the last lines in the poem “Tankard:” “gaslit street posts odds / rag & bone man drives panel / marked the good shepherd. / “My bucket.” she says of the picture.”10

The poems within The Herb Companion convey Bahnmiller’s feelings about her assault and an outline for Der Imker, which was commissioned by the Silvermans and was, at that time in 1994, a work-in-progress. She used small instructional booklets, diagrams, and manuals as an adjunct part of exhibiting from her first show, onward, and they frequently consisted of poetic digressions, like resource material that could guide the viewer deeper into her main body of work.

Read next: In The Shadows of Der Imker (The Beekeeper), inside Doom and Glory in the Cass Corridor: A Dossier on Cay Bahnmiller by Cary Loren

Lead image and Fig. 2, Cay Bahnmiller, Untitled (tankard), 1991, courtesy Gilbert and Lila Silverman collection.

Endnotes

1. Karen Roth, “Artist Transforms Detroit Into Antiquity,” review in Artspace, 1980.

2. Cay Bahnmiller, small black binder with foldout notes, sketches and slides, dated 1982, Gilbert and Lila Silverman collection in transit to the Detroit Institute of Arts.

3. Cay Bahnmiller, letter to Gilbert Silverman, Sept. 20, 1987, Gilbert and Lila Silverman collection.

4. Gilbert Silverman from “Gilbert Silverman Selects,” Focus Detroit Gallery, May 27-June 25, 1983, n.p.

5. Wendy Silverman, phone interview, Sept. 21, 2021, later quotes being from this interview.

6. Cay Bahnmiller, letter, April 10, 1991, Gilbert and Lila Silverman collection.

7. Cay Bahnmiller / Artist Statement, typed page, 1993, Gilbert and Lila Silverman collection.

8. Cay Bahnmiller letter, 1997, Gilbert and Lila Silverman collection.

9. For the Silvermans, this kind of close relationship with an artist wasn’t unusual; they communicated regularly with dozens of artists from around the world, maintaining an organized archive of folders on correspondences and other relevant information. They also held an extensive library of books and catalogues on the artists within their collection. In the mid-1970s, the Silvermans began working with advisor, curator, and scholar Jon Hendricks, who helped them amass one of the largest and most complete Fluxus collections in the world. For years, The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection was housed at the Parker-Webb building at 400 Grand River Avenue in Detroit. Though most of the Fluxus work was donated recently to MOMA—the Silvermans’ extensive Bahnmiller collection is now in the process of being transferred to the Detroit Institute of Arts.

10. Cay Bahnmiller, untitled seven-page staple-bound artist book, 1994, Gilbert and Lila Silverman collection.