Patching the Past

Reimagining the BuchlaBy Mark Milanovich

Synthesizers have been a big part of my life ever since I was old enough to save up to buy one at age fifteen, growing up in Lewiston, a small suburb on the outskirts of Buffalo, New York. My collaborator Chip Flynn and I have both been immersed in designing and manipulating electronic sounds since we were teenagers, but it wasn’t until Don Buchla came into the picture that the word synthesize took on deeper meaning.

Modular Electronic Music Systems (MEMS) is the name for my collaboration with Flynn, an electromechanical artist based in Detroit. The moniker is a nod to something that inventor Don Buchla scribbled on a schematic as an early name for his genre-defying and defining gift to the world: the pioneering Buchla modular synthesizer.

At MEMS, Flynn and I custom manufacture replica Buchla synthesizers. Flynn is the circuit specialist, builder, and mechanical designer. I handle circuit board generation, graphic design, and am also a circuit specialist. Our mission brings together our passion for technology with a shared ideology regarding the democratization of musical instruments. Until now, Buchlas have changed hands in private. The number of available systems that aren’t collecting dust in colleges are under careful observation in the hands of a few collectors and enthusiasts. In short, Don Buchla’s work is inaccessible to those who aren’t lucky or rich enough to gain access. The instruments are out of reach, behind paywalls at schools and behind the doors of music studios. By replicating them, we bring them out of the shadows of obscurity and put them in front of people who can learn and grow from the experience.

Kraftwerk once said that the bicycle was the ultimate bridge between man and machine. Similarly, the Buchla is the bridge between the composer and electronics. Most people discover it later rather than sooner, but it’s instantly addicting. Buchla brought alchemical thought to the creation of sound.

After receiving his degree in physics from the University of California, Berkeley in 1960, Don Buchla built his first voltage-controlled synthesizer in 1963. Meanwhile on the East Coast, Bob Moog was also working on his own synthesizer, which would become commercially available just a year later. But there’s a big difference between their two systems, with Buchla’s being better suited to exploring possibilities rather than commanding playback. It’s like if the two of inventors were steering a course, Moog would be at the helm of a yacht with all the bells and whistles, and Buchla would be out near the Andromeda Galaxy driving the Magic School Bus. Buchla was after new sounds, alien sounds, sounds that couldn’t be easily incorporated into a classical fugue or a pop song.

He disliked the term “synthesizer,” as it implied he was re-creating sounds rather than finding new ones. When synthesizers first became accessible to composers, few knew what to do with them. Some composers, like Wendy Carlos, used the synthesizer to emulate an entire orchestra. Patch notes dictated sounds and shoved them into categories, and, for many musicians, the synthesizer became an electronic replacement for brass and wind instruments. Don Buchla balked at the idea, as invented sounds were more aligned with the experimental nature of the system itself. If anyone would like a crash course in these bicoastal polarities, just listen to New York-based Carlos’ The Well-Tempered Synthesizer and then San Francisco-based Morton Subotnick’s The Wild Bull. The comparison is like night and day.

Don Buchla’s first complete system was called the 100 Series. It was not branded as a Buchla in the beginning, but these first 100 Series systems were built under the San Francisco Tape Music Center moniker. One purpose of what is now known as the Buchla 100 was to remove the necessity for tape loops. Sequencers were utilized to create repetitive passages with no cutting or splicing involved. The gestalt of this system did not necessarily evolve out of a cohesive vision, but Don approached the creation of the 100 as any problem-solving engineer would: waiting for input from the end-users and making adjustments or additions as needed. Morton Subotnick and Ramon Sender were essentially beta testers. The modules were created “outside-in”: Don would design the panel first to dictate what he wanted the module to do, then experimented with the electronics to figure out how to do just what the panel would indicate. This allowed the system to be designed in such a way that the musician performing it would feel the purest connection to the instrument. Once the 100 Series had evolved to the point of completion, Buchla moved onto the 200 Series, which was a more complete vision. Ideas fleshed out in the 100 were refined and modified. Modules were designed to be interconnected with other modules.

The sounds of a Buchla are more similar to those we take for granted than the ones we tune into: a book dropping squarely onto the floor, the rattle of a container skidding across a counter, even the cacophonous din of wind chimes on a summer night. These sounds are discovered through hands-on interaction with the instrument, in control of the spatial and timbral aspect of the performance through physical contact, through touch plate keyboards and microphone inputs for instance. (and even brainwave translation modules).

I was introduced to Chip Flynn by Mike Peake, a fellow builder and Buchla enthusiast, so it was no surprise when Flynn and I started working together as MEMS in late 2018. At the time, the only way to build these modular behemoths was by purchasing boards from a store that specialized in cloned Buchla modules. As availability plummeted, we both started tinkering with our own versions of the boards. This was an opportune time; Flynn had gained access to the Buchla 100 housed at University of Michigan’s Stearns Collection of Musical Instruments. We flooded each other with information and documentation, and it turned into an intense collaboration. He had documented circuit boards photographically with Lon Diehl of the industrial-experimental band Hunting Lodge, and I started to use those photos to replicate the circuit boards with period accuracy. We became the hunters and gatherers of all things Buchla, and the best part is that we did it by simply asking for access.

Asking got us into Wesleyan University to document David Tudor’s early Buchla 100 prototypes, which were commissioned after John Cage visited Don Buchla and experimented with 100 Series modules. After days of digesting the information, we were able to re-create them with period accuracy and breathe new life into modules that few have been able to use.

Replicating these rarities is akin to alchemy. Building a rare module gives a student or musician an invaluable opportunity. During our visit to Wesleyan, we brought a demo system to a symposium on compositions led by sound artist Ron Kuivila, and delivered a talk about the design process. Once the talk was over, we allowed the students to interact with the Buchla and observed the collective awe and excitement. We noticed them entering a state of what I could only describe as tabula rasa, tapping into their sense of childlike wonder. In moments like that, the magic, which escapes us as we age, returns.

I wish that Don Buchla were around to survey that classroom. He was always a forward thinker. Case in point, during his later years, he dismissed the opportunity to reproduce his work—not out of concerns over intellectual property, but because he felt the modules were already old hat.

I’m sure that even if Don Buchla dismissed the idea of Flynn and me bringing his modules back to life, he would have appreciated watching the students work with his synthesizer like they were having a blast on the playground. Unlocking and activating that moment is what he intended from the get-go—the discovery of new sounds at the bleeding edge of foreign landscapes and dimensions we thought were unreachable.

Chip Flynn began his career as an electromechanical artist in 1988. He worked for the San Francisco group Survival Research Laboratory, led by electromechanical pioneer Mark Pauline, and formed his own similar group Peoplehater in 1992. He is a founding member of the electromechanical art collective Apetechnology in Detroit.

Mark Milanovic is the founder of Vektor Electronics, a company seeking to merge gaps between synthesis and guitar effects. Notable owners of Vektor guitar pedals include Lee Ranaldo of Sonic Youth and Steve Albini, prominent producer and engineer at Electrical Audio. He is also a founding member of the NEON_SEA collective group, a band of musicians with experimental electronic composition as its modus operandi.

For more information on MEMS, visit memsproject.info.

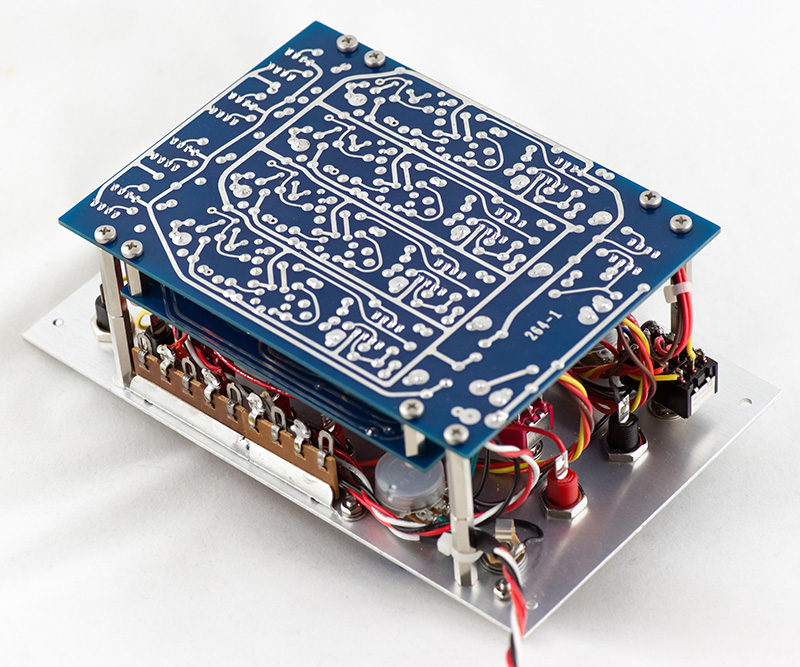

Fig. 1 Completed MEMS Module 264 Quad Sample and Hold, with period accurate boards built by Dave Brown of Modular Synthesis. Courtesy MEMS

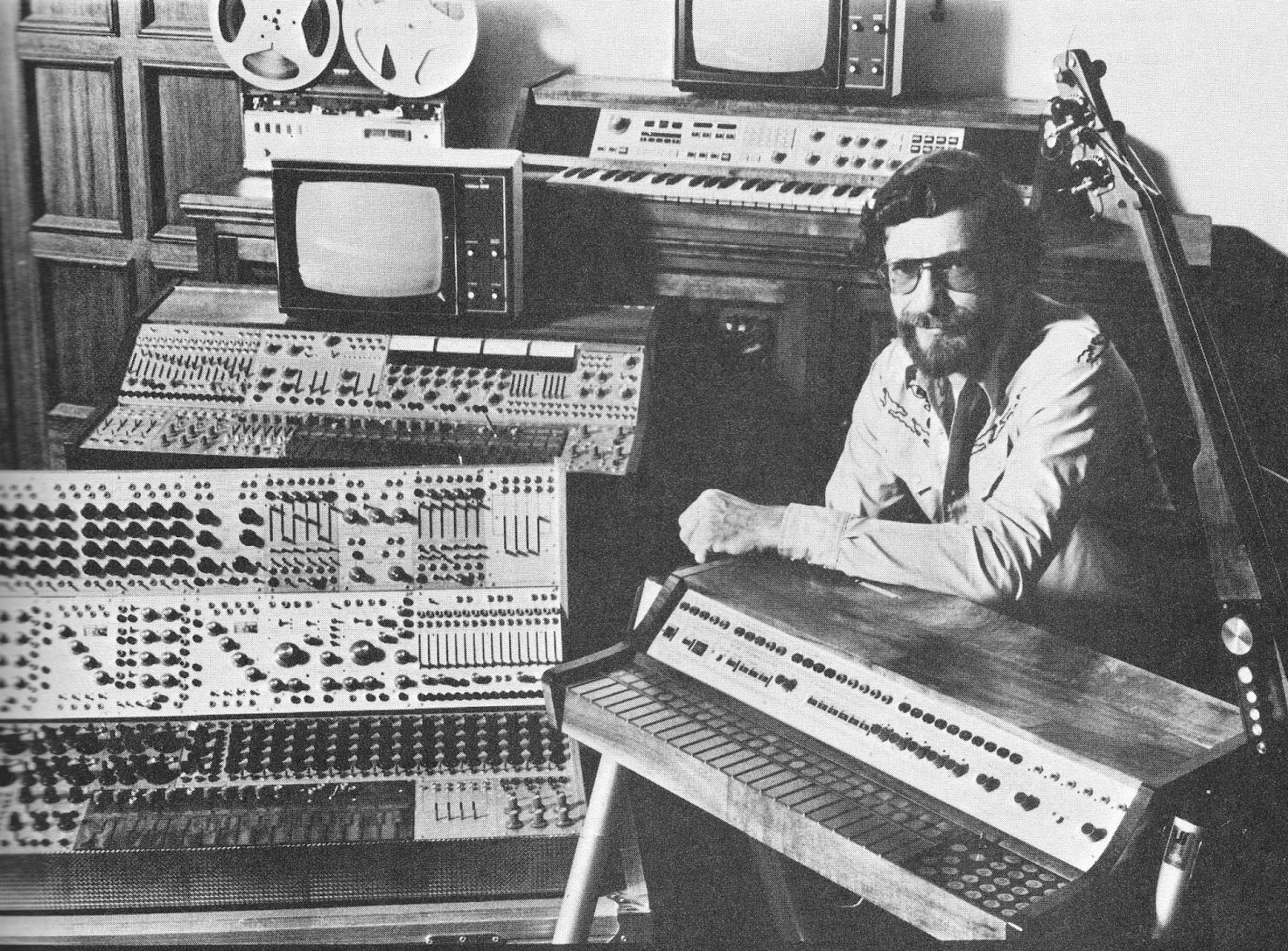

Fig. 2 Photo of Don Buchla c. 1960s. Courtesy Buchla.com

Read next: Imaginary Dinner Party: Part Three, Think Like a Detective by Lynn Crawford