Men of the Cloth, Men of Capital

An ongoing series on civil rights in Detroit in the 1940s

By Michael Jackman

Detroit is packed with Southern white hillbillies … many of its policemen [are] Southern [and] it is full of company thugs, ex-Bundists and Ku-Kluxers.

–John Gunther, Inside U.S.A., 1947

In the early 1940s, Detroit’s racism was an open secret across the country. As the area’s industrial plants prepared for a war against fascism, the Ku Klux Klan was trying to recruit many of the tens of thousands of Southern white migrants arriving in Detroit for work.

Officially, the FBI called it “a moderate revival.”2 Right-wing terror groups had been active in Detroit for a generation. Starting in the mid-1920s, the Ku Klux Klan not only claimed a large membership in Detroit, mass rallies were sometimes conducted in public, as on Christmas Eve, 1923, when thousands of Klan members not only burned a cross in front of City Hall, but welcomed a Santa Claus, clad in a mask and robe, to entertain the children.3

These hate groups opposed many of the same things the city’s industrialists did, using methods little different from company officials. In the workplace, the auto companies used spies, informants, and thugs to neutralize unions. Ford Motor Company ran the Ford Service, a private police force composed of head-cracking goons. General Motors was one of the largest clients of the vast private security and strikebreaking firm, the Pinkerton detective agency.4

Even though it was ultimately about power, there was a distinct racial dimension to this conflict. Detroit’s magnates and managers often relied on extremists to get their way. White supremacist organizations generally opposed unions, hated Communists, and espoused bigoted nativist views that were hostile to populations of marginalized workers union organizers might appeal to: immigrants, Catholics, Jews, and Black people. As such, right-wing zealots presented a ready-made force that the city’s powerful leaders would carefully nurture and increasingly bring to bear.

Over the years, it became clear that these extremists were funded by the wealthy, and in 1936 that fact was practically sensationalized when a Klan offshoot known as the Black Legion became one of the year’s biggest news stories. A probing series of trials revealed that as many as 100,000 men belonged to the group across the Midwest. Subsequent investigation into the Legion revealed that many of its members were police, prosecutors, Detroit-area politicians, and business leaders. Their activities included union-busting, collusion with company spies, a dozen murders, and even a bomb plot.5

After a long summer of exposure in dramatic news headlines, the point was unmistakable—large industrial concerns were paying the groups to harass and inform on unions, frighten organizers and left-oriented Detroiters, and even liquidate perceived troublemakers.

So isn’t it interesting that at the very moment these terror groups scurried away from the glare of publicity, men of the cloth showed up? From the mid-1930s on, religious white right-wingers became a conspicuous presence in Detroit, preaching sermons with resentment and chauvinism. They often traveled far and wide, bestowed with generous funding or wide-reaching platforms. Sometimes, they were little more than self-promoters using the trappings of religion to grant some measure of resistance to official investigation.

The best-known of these was Father Charles E. Coughlin, the Canadian-born priest who published his own newspaper and broadcast his views on radio across the country from the Shrine of the Little Flower in suburban Detroit’s Royal Oak. Coughlin found support for his defenses of the Axis Powers among Roman Catholics, at least until he was forced off the air on the war’s eve and compelled into silence on political matters.6

Another prophet of the right in Detroit was J. Frank Norris, now regarded as the father of Christian fundamentalism. In Texas, he was a leading Baptist minister. But in 1935, the reverend accepted the pastorate of Temple Baptist in Detroit, commuting by train and airplane between his two flocks, which soon numbered in the tens of thousands. Detroit’s Appalachians flooded into church to hear him, or tuned him in on the radio, drawn by his denunciations of minorities, whom he described as consisting of “rapists” and “primitives” that should remain strictly segregated.7

For an adherent of the “Prince of Peace,” Norris was no stranger to bloodshed. He once shot a man to death in his Fort Worth office, although he claimed it was in self-defense.8 And eyewitnesses reported that, on Nov. 9, 1939, he led his parishioners from Temple Baptist down the street, where they attacked people leaving an address by the chairman of the Community Party USA. The celebrity pastor said he had not led the picketers, but that he had only gone down the street out of curiosity. No doubt many from his congregation joined the groups who attacked the crowd of several hundred,9 which included about two dozen Black attendees.10 At least 20 people were injured, with some attackers yelling, “Lynch them!”11

Little remembered today, the Rev. Gerald L.K. Smith was a political organizer, fascist sympathizer, and former assistant to Huey Long who moved to Detroit to run for office on a “rootin’-tootin’ rip-snorting” Tires for Everybody campaign that included a synthetic tire he carried across the state as a prop. A barely concealed racist, a foe of integration, and a rabid anti-Communist, he took to the local airwaves and published a propaganda magazine called The Cross and the Flag.12

Though Smith was known for his continual appeals for donations on radio and at rallies, the resources at his command suggested major backing: In his 1942 run for U.S. Senate, he outspent both his Republican primary opponents, and directed his political activities from a luxurious office occupying an entire floor of Detroit’s Industrial Bank Building. Some hinted that his real funders were prominent New Yorkers.13

After losing his U.S. Senate run, Smith continued his crusades in Detroit. He led a crowd of 100 picketers to protest at Wayne University on April 14, 1943, when Langston Hughes spoke there, calling the poet “an atheistic communist … and a notorious blasphemous poet.”14 Following Detroit’s bloody 1943 race riot in which more than two dozen Black people died, 14 national organizations appealed to the Department of Justice to seek his indictment in connection with the outbreak of violence.15

I have never known the police of any country to show an interest in lyric poetry as such. But when poems stop talking about the moon and begin to mention poverty, trade unions, color lines and colonies, somebody tells the police.

–Langston Hughes, “My Adventures as a Social Poet,” W.E.B. Du Bois’ Phylon magazine, 1947

Right-wing religiosity included the “worker-preacher movement,” in which Southern whites who worked on the assembly line during the week became lay preachers in storefront churches on Sunday. Some auto plants, such as Dodge Main, Dodge Mound Road, and DeSoto, supported their activities with makeshift pulpits or “Pleasant Valley Tabernacles” within the factories. Their tent revival-style sermons were often anti-Semitic, anti-union, and anti-Black.16 Some of their performances involved crude, nationalistic antics, reminiscent of those by the widely traveled Colorado preacher Harvey Springer, the “cowboy evangelist” who earned applause by trampling on the flags of foreign countries before holding the American flag aloft.17

This movement was energized by dozens of broadcasts lighting up Detroit’s radio frequencies every day.18 In fact, area broadcasters regularly listed more than 70 or 80 religious programs each Sunday, many in the style of Coughlin and Norris.19 From the shop floors to the airwaves over the city, in hundreds of sermons a day, these homegrown apostles complained about new ideas, such as integration and left-leaning labor organizations, appealing to the hundreds of thousands of people jarred by their recent arrival in the city.

Writing for The Crisis in the 1940s, Michigan Chronicle editor Louis E. Martin called wartime Detroit a “national ‘testing ground’ for every new crackpot design for living and every political nostrum from Technocracy to Coughlinism. It is not surprising either that the Black Legion was cradled here, that the Ku Klux Klan has flourished, and that such demagogues as Gerald L.K. Smith, Frank Norris, and Father Coughlin are able to hold the center of the city’s ‘cultural’ stage.”20

The violent anti-Communism of Norris and other preachers carried special significance to many Black Detroiters, as Communists were among the few sincere and hardworking allies available to them. Arthur McPhaul would later say, “They were the only ones, as far as white people were concerned … really out in the front fighting. And many Blacks attended their affairs and so forth. They used to have what they called a workers camp, where Blacks used to go, and, of course, the fascists finally burned that down.”21

Detroit’s Communists, however, did not have an easy time recruiting Black Detroiters to their cause. Their calls to reject religion as superstition and embrace international brotherhood resonated poorly among Northern city-dwellers.22 Additionally, Chronicle editor Louis E. Martin claimed, “The Communists … went beyond the race thing to say something about … Russia, or some other goddamn international event.”23

“The urgency of the existing current situation was always upmost in Blacks’ thoughts,” Martin said. “They had no ideological, long-range views about some ideal state; what they wanted was a share of what they saw.”24

The ideas of Detroit’s broader left failed to reach the people who needed to hear them most. Detroit’s labor leaders were unable to find a way to challenge bigoted attitudes among their rank and file. Their overreliance on publicly denouncing the likes of Smith and Norris changed nothing, since “all of their activities took place almost exclusively on the level of negative propaganda,” as scholar Angela Dillard has noted.25

Few people in Detroit were in a position to see these obstacles clearly. Even fewer had the means to speak to both white and Black workers in their own language, to acknowledge their earthly needs and to respect the religious way they often framed their existence. And these tensions were only growing more serious: In 1939, Chrysler executives tried to disrupt a strike by fomenting a race riot between Black workers and white strikers. Two years later, Ford Motor Company would try the same tactic.26

These and other challenges inspired a small group of Detroit social workers, church leaders, and public-spirited citizens to seek outside help. Early in 1941, they appealed to the Rev. Claude C. Williams, head of the People’s Institute of Applied Religion (PIAR), which had been active in Arkansas and Tennessee.27

Claude Williams had grown up as the son of tenant farmers in western Tennessee, “so far back in the sticks they had to pump in daylight to make morning.” He attended Bethel College, a conservative Tennessee seminary, in the 1920s, there meeting his future wife, Joyce King, daughter to a Missouri farming family. The couple first pastored near Nashville, but became increasingly uneasy about Southern segregation. Soon, Claude and Joyce Williams were being shuffled from job to job for defying Jim Crow.28

By the late 1920s, they had become truly radicalized. Williams was greatly influenced by The Modern Use of the Bible, a book by prominent liberal pastor Harry Emerson Fosdick. In 1927, Williams enrolled in summer seminars at Vanderbilt University led by Dr. Alva W. Taylor, a Southerner who was a member of the Socialist Party. Williams was transformed by the way Taylor swept away centuries’ worth of theological debris away from Jesus of Nazareth to reveal the true Son of Man “and let Him rise among us as a challenging human leader.”29

By 1930, Williams’s conversion to the social gospel was well under way. He and Joyce embarked on what they would eventually see as their true religious calling: organizing working-class people into leaders of social movements. Williams accepted a pastorate in Paris, Arkansas, in the heart of the state’s mining district. The couple invited organizers of the United Mine Workers of America into their church, helping raise funds, and plan strategy. The crusading reverend traveled hundreds of miles through coal country, giving speeches to union members. In ensuing years, he was ousted from his pulpit more than once and thrown in jail for participating in protests.30

To escape terrorism from police and vigilantes, the Williamses moved to Little Rock, where they held the first classes of what they called New Era Schools. These leadership classes helped train organizers for the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. This put the fledgling endeavor at the center of an emerging general labor and civil rights struggle involving unemployed councils, the Workers Alliance of America, the Socialist Party, the Communist Party, and colleagues from Commonwealth College, a Marxist labor school at Mena, Arkansas.31

The reverend honed the art of communicating with Southern tenant farmers, Black and white, as they tried to build a real interracial movement for social justice. Claude and Joyce Williams both understood and respected that the people they hoped to reach were strongly conditioned by religion. As one observer summarized the attitude of many Southerners: “Everything that it means to be good, to live honorably, to find support through life’s trials and hope in the future—these are the profound personal and social questions that poor Southerners have answered in religious ways for generations. The Bible is the book that points the way. For many, it was the only book they ever read.”32

Williams found that, among Black congregations, the support of the pastor was absolutely crucial for the success of any organizing drive. “As we spoke with the sharecroppers, we were obliged to meet in churches,” Williams later recalled. “And it developed, especially with the Black churches, that the pastor usually was present and chaired the meetings. Unless he said ‘Amen’ with that certain inflection which got the people to saying ‘Amen’ and rumbling their feet, we might as well go home.”33

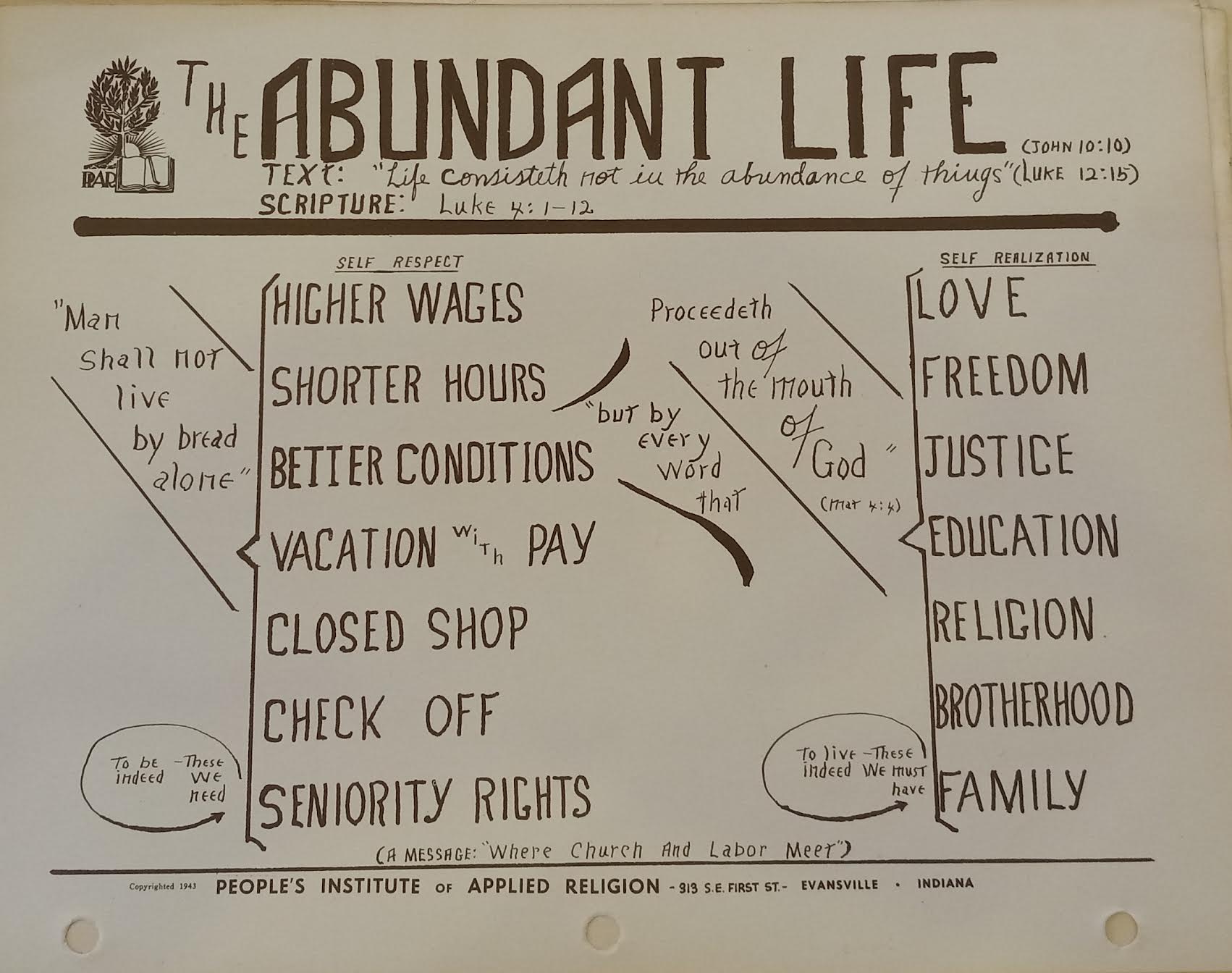

With the help of artists, Williams began developing what he called “orientation charts”—visual aids that helped preachers convey the institute’s radical interpretation of the Gospel. Williams had seen how sharecroppers were unprepared to wade into the political tracts activists often offered them. Summarizing the reverend’s intentions, interviewer Bill Troy wrote, “They needed something visual, something more symbolic than literal, something that would suggest concepts based on the story people were already familiar with—the Bible.”34

As part of institute retreats, Williams invited participants to share their woes in sessions that sounded almost like encounter groups. Rising leaders from impoverished districts in the countryside sometimes talked for long periods about the problems they faced, using their own language. The experience was powerful for those who spoke and those who listened, hearing the predicaments of other working people and validating their feelings. “We learned we had to contact these people at their consciousness of their need,” Williams said. “We recognized that what the social scientist or the social worker saw as the need of the people and what the victim felt were two entirely different things.”35

But the most revolutionary aspect of the Williamses’ retreats was their interracial nature. Between a dozen and two dozen participants, evenly divided between Black and white, would spend each day working together, dining together, worshiping together, singing hymns together. “It was the first time some of them had ever been together in a meeting,” Williams recalled. “Most, if not all of them, had never sat down to a meal together, and most of them thought they never would—especially the whites. The Blacks never thought they’d have the opportunity.”36

Such interactions released powerful emotions. Some participants broke down into tears, overcome by the experience of interracial fellowship. One unlikely convert was the Rev. A.L. Campbell, a white Arkansas sharecropper who’d actually enrolled in classes at the PIAR as a spy for the Ku Klux Klan. In a 180-degree conversion, he renounced his membership in the Klan, accepted ordination from the institute, and became one of its most energetic and effective leaders.37

What’s more, Williams shared his pulpit with energetic Black preachers who respected his visual, vernacular approach to applied religion. Among them was the Rev. Owen Whitfield, a cotton field preacher from Missouri. In one sermon, Whitfield declared, “Religion is like a bottle of liniment on the shelf; it is no good to a man with a cut finger, unless it is taken down, uncorked, and applied.38

As a radical reverend who’d spent years traveling the South and meeting its working people, Williams was aware of the many tens of thousands of Southerners streaming into Detroit, and the right-wing organizers massing there to win them over to the side of division and hatred. By February 1941, a group of Detroit progressives established a sponsoring committee to bring the Williamses and their institute to the Arsenal of Democracy. In early 1942, Williams accepted the invitation of the Presbyterian churches in Detroit to establish a labor ministry.39

It was an invitation the Detroit Presbytery would later reconsider. The Rev. Claude C. Williams immediately set about exposing not just the reactionary forces at work in the city, but their connection to wealthy business interests. Drawing on his informants far and wide, he compiled an exhaustive list of charges that powerful industrialists, reactionary religious figures, and violent head-crackers were all working together to whip up trouble in Detroit. He sent his screed to the leadership of Detroit’s Presbyterian churches, to magazines, and to newspapers. An edited version of the manuscript was published in The Protestant under the title “Hell Brewers of Detroit”—and promptly set off a controversy the PIAR’s supporters didn’t necessarily welcome.40

The institute republished the article as a pamphlet and distributed it widely. It told of the national leader of the KKK’s frequent visits to Detroit. It offered the latest intelligence, often including the names of officers, addresses, and activities, of the Dixie Voters’ League, the Southern Society of Michigan, the America First Party, the British-Israels, the Christian Businessman’s Committee, the Friends of the Little Flower, the Laymen’s League, and summaries on storefront and basement preachers. The booklet offered damning statements about Baptists churches serving as Klan recruitment centers and preachers teaching racism, anti-Semitism, and anti-unionism in sermons.41

As controversial as the charges in the pamphlet were, the reverend had access to raw data that few editors, even in national publications, would have considered publishing. The People’s Institute of Applied Religion had several informers embedded in the KKK and other organizations feeding intelligence that included a number of controversial allegations. A PIAR fact sheet on file indicated that Temple Baptist was a stronghold of Klan affiliation, and that the Rev. J. Frank Norris was an active member of the Ku Klux Klan. It alleged that all religious services in the Packard Plant were under the supervision of men who held leadership positions at Norris’s church.

This same backgrounder also noted that Henry Ford had flown Norris around the world twice, even during wartime when “such passage was restricted to the highest Army officials and international political figures.” The obvious surmise was that Ford ensured that one of the Klan’s most effective organizers traveled by Clipper.

Charges included that General Motors was bankrolling anti-union speaking tours by Norris, using local religious functionaries as “bagmen” to secretly fund them. It also offered details of a meeting at the mansion of Chrysler executive B. Edwin Hutchinson in the winter of 1941–1942, in which a dozen or more were present, including Norris, his assistant, and several representatives from General Motors. It alleged a similar meeting took place at Grosse Pointe Memorial Church in the wealthy suburb bordering Detroit, according to the Rev. Frank Pitt—a statement the reverend later denied.42

The mention of B. Edwin Hutchinson—misspelled by the PIAR as “Mr. Edward Hutchinson, Treasurer of the Chrysler Corporation”—rings true. Seldom recalled today, when B.E. Hutchinson died in 1961 he was remembered as one of the auto industry’s “pioneers and greats.”43

“Hutch” was a smooth operator. He certainly was in an excellent position to organize the meeting described in the PIAR’s files. He was a dynamic, determined, gregarious man whom his friend, a Detroit newspaper editor, called a “scholar in the study of relative religions,” making him a good intermediary between religious people and capitalists.

Detroit’s auto barons brought the former efficiency consultant in at Maxwell Motors in 1921. By the 1930s, “Hutch” was an elite executive in Detroit, the highest paid vice president at Chrysler, with an annual salary and generous stock distributions that easily made him a millionaire. He had a home in the city’s prestigious Indian Village neighborhood, as well as an exclusive Rhode Island estate called Weatherledge on Narragansett Bay, where he plied the waters on his motor yacht, not to mention his sprawling new residence in neighboring Grosse Pointe.44

Hutchinson had compelling motives to make a deal with the devil if it kept the union at bay. An executive whose entire career was based on his ability to dictate terms to workers would naturally see industry-wide negotiation as an existential threat. Such a person might be willing to take ever larger risks, to invite disorder that might bring in the National Guard to keep a peace more to his liking. After all, in 1939, Hutchinson’s company tried unsuccessfully to foment a race riot at the Dodge Main plant. And his unsavory association with Norris ties him to Ford, whose Rouge Plant saw another botched race provocation in 1941.

Thanks to his informers, the reverend knew very well that fanatics appealed to the powerful industrialists who saw it in their interest to promote them. Speaking to a Detroit reporter, Williams said, “America’s feudal South … needed no instruction from Hitler in the gentle art of race persecution. … And certain interests here, afraid of the general trend postwar democracy may take, have been willing to support these imported Southern movements to see what will happen.”45

Williams declared that the stakes of this struggle were high: nothing less than the soul of the nation after the war. He warned that “the hundreds of thousands of ex-rural people who now crowd every war center must be reached in their new situations if fascism in this country is to be prevented.” He alleged that this array of powerful organizations preaching fear and hatred of minorities and organized labor was part of a worldwide offensive “to grasp the war leadership from the liberals and change its objectives from the Four Freedoms to a fascist imperialism of some sort.” Lest his point be missed, he stressed that “certain political and industrial interests … are financing the entire affair.”46

The Tennessee-born preacher and his wife spent several years in Detroit, ministering to interracial groups, union members, and even leading efforts to persuade religious groups into social work. Like others in the city, Claude Williams marched and protested and carried signs. But what set him apart in Detroit was his willingness to discuss the role of the wealthy and powerful in promoting bigoted religion and extremist politics to exert social control. And he had a natural ability to explain it without platitudes.

In this way, he would not just strike out at Norris, Smith, or Coughlin, as others routinely tried, but expose their funders. Asked about the Hearst-led, business-funded Youth for Christ movement, for instance, Williams went right for the moneychangers: “The main reason why the money moguls started Youth for Christ was to give young people a dose of what they call ‘the old time religion.’ They wanted to keep the kids out of any new youth movement … Remember how the cotton bosses always start revivals on the plantation when the pickers want a dime more for breaking their backs in the hot sun?”47

The Rev. Claude C. Williams spent several years in Detroit as a fighting pastor, but arriving in town and telling the truth won him powerful enemies. His organization eventually wilted under the heat of controversy. The group disbanded in 1948, and he was removed as a Presbyterian minister in 1954. Yet for all the trouble his campaigns caused him, Williams never regretted informing on Detroit’s peddlers of extremist religion and white supremacy. “Perhaps it might be said without being immodest,” he surmised later in life, “that PIAR probably raised more constructive hell in the late 1930s and 1940s than any other religious movement in the country.”48

Endnotes

[1] John Gunther, Inside U.S.A., (New York and London: Harper & Brothers, 1947), 286.

[2] Federal Bureau of Investigation, report entitled Foreign Inspired Agitation Among American Negroes in the Detroit Field Division, 7/8/1943, 46.

[3] “Police Quell 2,000 in Klan Riot at County Building,” Detroit Free Press, 12/25/1923, 1, 3. For a discussion of rallies of the Ku Klux Klan in the mid-1920s, see Kenneth T. Jackson, The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 130–132.

[4] Stephen Meyer, Manhood on the Line (Urbana; Chicago; Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2016), 58–59, 61; Pinkerton client from “Summary of Senate Sub-Committee’s Report on Use of Espionage in Industry,” New York Times, 12/22/1937.

[5] Christopher H. Johnson, Maurice Sugar: Law, Labor, and the Left in Detroit, 1912–1950 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1988), 181–186.

[6] For a skeptical view of Coughlin’s initial anti-KKK stance, see Donald Warren, Radio Priest: Charles Coughlin, The Father of Hate Radio (New York: The Free Press, 1996): 15–19; Leslie Woodcock Tentler, Seasons of Grace: A History of the Catholic Archdiocese of Detroit (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1990), 322–324, 340–344.

[7] “To Detroit Church,” Windsor Star, 1/3/1935, 8; a typical advertisement appears for “Dr. J. Frank Norris” at “Temple Baptist Church, 14th and Marquette,” “Morning service broadcast over Radio WXYZ,” Detroit News, 11/4/1939; Alan Clive, State of War: Michigan in World War II, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1979), 139.

[8] “Dr. Norris Slays D.E. Chipps—Lumberman Dies After Shooting in Office of Church,” Fort Worth Star Telegram and Sunday Record, 7/18/1926, 1, 6.

[9] “20 Injured in Fighting After Rally: Communists in Clash With Pickets,” Detroit News, Friday, 11/10/1939, 1.

[10] Arthur McPhaul, Box 2, Folder 21, 6–7, Blacks in the Labor Movement Oral History Project, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University, Detroit.

[11] “Detroit Vets Battle with Communists Four Held by Police,” Detroit Free Press, 11/10/1939, 1.

[12] Drew Pearsons, Merry-Go-Round column, Detroit Free Press, 9/11/1942, 6; Walter White and Thurgood Marshall, What Caused the Detroit Riot (New York: National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, July, 1943), 7–8; “The Primary in Michigan,” Green Bay Press-Gazette, 9/18/1942, 4; his 15-minute 7:15 p.m. radio appearance on WJR, often identified as an “interview” format as opposed to “religious,” is listed in the Radio Log, Detroit Free Press, 1/4/1942, Part Four, 4; 4/26/1942, Part Two, 7; 7/5/1942, Part One, 8; 10/4/1942, Part Two, 7; 11/1/1942, Part Two, 9; as of September 1942, a Detroit newsman said he had been speaking over the radio in Michigan for two years, see James M. Haswell, “Gerald L. K. Smith in the Home Stretch,” Detroit Free Press, 9/13/1942, 1. A sample of Smith’s ideas on separation of the races from The Cross and the Flag is included in Alfred McClung Lee and Norman Daymond Humphrey, Race Riot (New York: Dryden Press, 1943), 63.

[13] His donation-seeking prompted several letters to the editor, one dubbing him “pan-handler Smith,” Detroit Free Press, 9/15/1942, 6; “Michigan’s Senate Race Is 1-Man, 3-Ring Circus,” Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin), 9/14/1942, 7; America First Party office location from R.L. Polk & Co., Detroit, Michigan, City Directory, 1941, 126; Hub M. George, “Smith Spent $10,612 on Vote Drive,” Detroit Free Press, 9/30/1942, 13; Smith’s campaign chest donors suggested for senate scrutiny in Drew Pearson and Robert S. Allen, Washington Merry-Go-Round, Press Democrat (Santa Rosa, California), 9/12/1942, 10; “big money” from “Eaton ‘Dares’ Smith to Disclose Donors,” Lansing State Journal, 8/21/1942, 3; New York backers suggested by Leonard Lyons, Detroit Free Press, 5/20/1942, 22.

[14] “Blowout: Smith Rides Tire to Fall but Crusade Will Row On,” Detroit Free Press, 9/17/1942, 19; Arnold Rampersad, The Life of Langston Hughes, Volume II: 1941–1967, I Dream a World, (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 69; Philip A. Adler, “Local, International Plot Clues Plentiful,” Detroit News, 6/25/1943, 1, 4; “Appearance of Poet at Wayne U Protested,” Detroit Free Press, 4/15/1943, 21; “Gerald Smith, Rev. Hill Debate Langston Hughes Issue,” Michigan Chronicle, 5/8/1943, 4.

[15] Lee and Humphrey, 63–64.

[16] Clive, 138; Babson, 115–116.

[17] Clive, 140–141; for mention of Springer’s popularity at his home church in Englewood, Colorado, and across the country, see Curtis Hutson, Great Preaching on the New Year, (Murfreesboro, Tenn.; Sword of the Lord, 1987), 54.

[18] “Shadow of Fascism Seen on Race Riots,” Detroit News, 7/1/1943, 20.

[19] A representative radio guide for June 20, 1943, the day the race riot began, lists a total of 83 broadcasts either religious in nature or emanating from houses of worship, “Radio programs,” Detroit News, Part Two, 12.

[20] Louis E. Martin, from “Detroit—Still Dynamite,” The Crisis, January 1944, 8–10, 25, quote on 9.

[21] McPhaul, 6.

[22] Studs Terkel, Hard Times, (New York: 1970, Pantheon Books, Random House), 436.

[23] Interview with Louis E. Martin, Side 1, 21:30–22:30, Dominic J. Capeci, Jr., The Detroit History Project: Oral Histories, The Detroit Riot of 1943, Bentley Historical Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

[24] Martin, Side 1, 24:13–24:32.

[25] Angela Dillard, Faith in the City, (University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, 2007), 140.

[26] August Meier and Elliott Rudwick, Black Detroit and the Rise of the UAW(New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), 67–71, 87–105.

[27] Letter to Mrs. W.M. Ostrander, 95 Tyler Ave., Detroit, from Oscar G. Starrett, Henry D. Jones, Robert C. Stanger, 2/15/1941, and Letter to Mrs. Pauline Bass, 8932 LaSalle Blvd., Detroit, 2/24/1941, from Oscar G. Starrett, Box 18, Folder 10, “PIAR Correspondence,” Claude C. Williams Collection, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University, Detroit.

[28] King maiden name from finding aid, Williams Collection; Terkel, 328–329; Bill Troy with Claude Williams, “People’s Institute of Applied Religion,” Southern Exposure, 4 (Fall 1976), 46, clipping in Box 18, Folder 1, “PIAR Articles”.

[29] Troy, 47; quote from Terkel, 328.

[30] “About the People’s Institute of Applied Religion,” answers to questions posed by the Rev. Arthur Carl Piepkorn, 1–2, Box 18, Folder 1, “PIAR Articles”; Troy, 47.

[31] Troy, 47.

[32] Piepkorn, 2.

[33] Troy, 48.

[34] Troy, 49.

[35] Troy, 48–49.

[36] Troy, 48.

[37] Troy, 48, 51.

[38] Whitfield as “cotton field” preacher from Troy, 51; quotes from sermon on “applied religion” from pages 45–48, clipped from publication, headed “Prophetic Religion in the South,” N.D., Box 18, Folder 1, “PIAR Articles”.

[39] Letters to Mrs. W.M. Ostrander and to Mrs. Pauline Bass, and fundraising document, “Detroit Sponsoring Committee of the People’s Institute of Applied Religion, Inc.,” Box 18, Folder 10, “PIAR Correspondence”; Troy 52.

[40] In a note by Claude C Williams attached to the cover of the pamphlet reprint, “the hell brewers told the Presbyters what to do. They obeyed: defrocked the ‘Red.’”—Box 18, Folder 13, “Hell Brewers of Detroit”.

[41] “Hell Brewers of Detroit”.

[42] “PIAR had colleagues who became members of the KKK in Florida, Georgia, and Michigan, [reporting on Klan leaders that included] Charley Spare and J. Frank Norris of Detroit,” Piepkorn, 3; “Confidential: File Resource”.

[43] “B.E. Hutchinson, Former Chrysler Executive, Dies,” State Journal (Lansing), 9/28/1961, 42.

[44] “Chrysler’s Hutchinson, Chevrolet’s Coyle, Die,” Detroit Free Press, 9/28/1961, 1, 2; Transcript-Telegram, 8/4/1921, 4; “Hearst and Mae West Head List of Nation’s Big Salaries,” Detroit Free Press, 1/7/1937, 5; “Who Goes Where,” Detroit Free Press, 8/30/1936, III, 11; “J.N. Pew, Jr., Gets Gift of $5,000,000,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 4/1/1936, 23.

[45] “Shadow of Fascism Seen on Race Riots,” Detroit News, 7/1/1943, 20.

[46] “People’s Institute Moves Headquarters to Detroit,” Detroit News, 7/10/1943; “to grasp” and “certain interests” from “Shadow of Fascism Seen on Race Riots,” Detroit News, 7/1/1943, 20.

[47] “Group Fights Suburb Action,” Detroit Free Press, 11/25/1944, 5; “Rev. Whitfield Will Keynote Conference,” Detroit Free Press, 7/22/1944, 8; “Church Body Plans Parley,” Detroit Free Press, 7/17/1944, 4; “Strikers Pray,” Detroit Tribune, 7/13/1946, 1; “Living South,” Detroit Tribune, 11/10/1945, 6.

[48] “Presbytery Removes Minister,” Detroit Free Press, 3/3/1954, 2; Troy, 52; Piepkorn, 3.

Fig 1–2 Claude C. Williams Collection, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan.

Michael Jackman spent fifteen years at Detroit’s Metro Times, where he started as copy editor and worked his way up to senior editor. He is in the process of completing his nonfiction book about Detroit in the 1940s.

Also from this series, by Michael Jackman:

A Case Study of Northwestern High School

Also from this series, by Michael Jackman:

A Case Study of Northwestern High School