Looking Past the Exploitative Lens, Fighting Against Erasure

An ongoing series on civil rights in Detroit in the 1940s

By Michael Jackman

Author’s Note

Twenty years ago, I walked into the Burton Historical Collection at the Main Branch of the Detroit Public Library looking for information on the 1943 Detroit Race Riot.

Having grown up in a typical white suburb meant I was raised on horror stories about Detroit’s 1967 rebellion, often presented by the white adults I knew as a “race riot.” And yet I had hardly ever heard about Detroit’s riot in 1943, in which white mobs took over Woodward Avenue looking for Black victims, and white police shot at least 18 Black people dead. That makes sense when you consider all the myths that story runs against: the Greatest Generation in the Arsenal of Democracy, Detroiters joining together in a united fight against fascism and ideas of racial supremacy. The erasure of this subject from discussion—a bloody wartime riot in which at least 35 people died—presented a stark contrast and, although I didn’t know it at the time, I was in the early stages of writing a book on the subject.

I was eager to learn more about what happened in 1943, a pivotal moment in Detroit’s history, when the NAACP and the UAW-CIO helped create a real civil rights movement. At the library, I gained access to more information than I had expected. From storage deep underground, librarians brought up massive original Detroit House of Correction logs from 1943, and boxes of original correspondence sent to Mayor Edward J. Jeffries Jr., including one of the major sociology reports of those jailed on riot charges. Over the years, I would come to recognize librarians there by face as I requested these and other materials, taking handwritten notes, making photocopies, and snapping digital photos for analysis later.

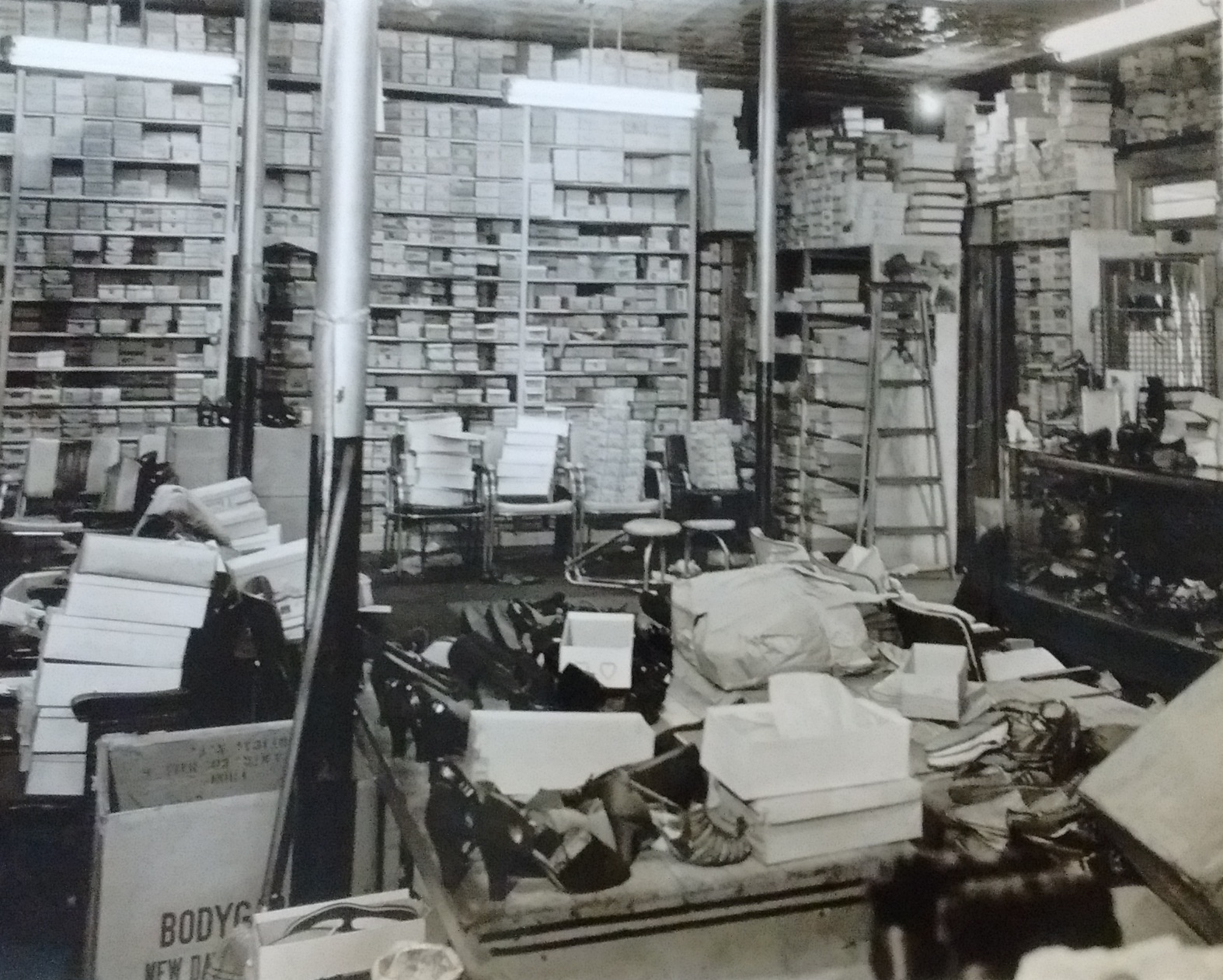

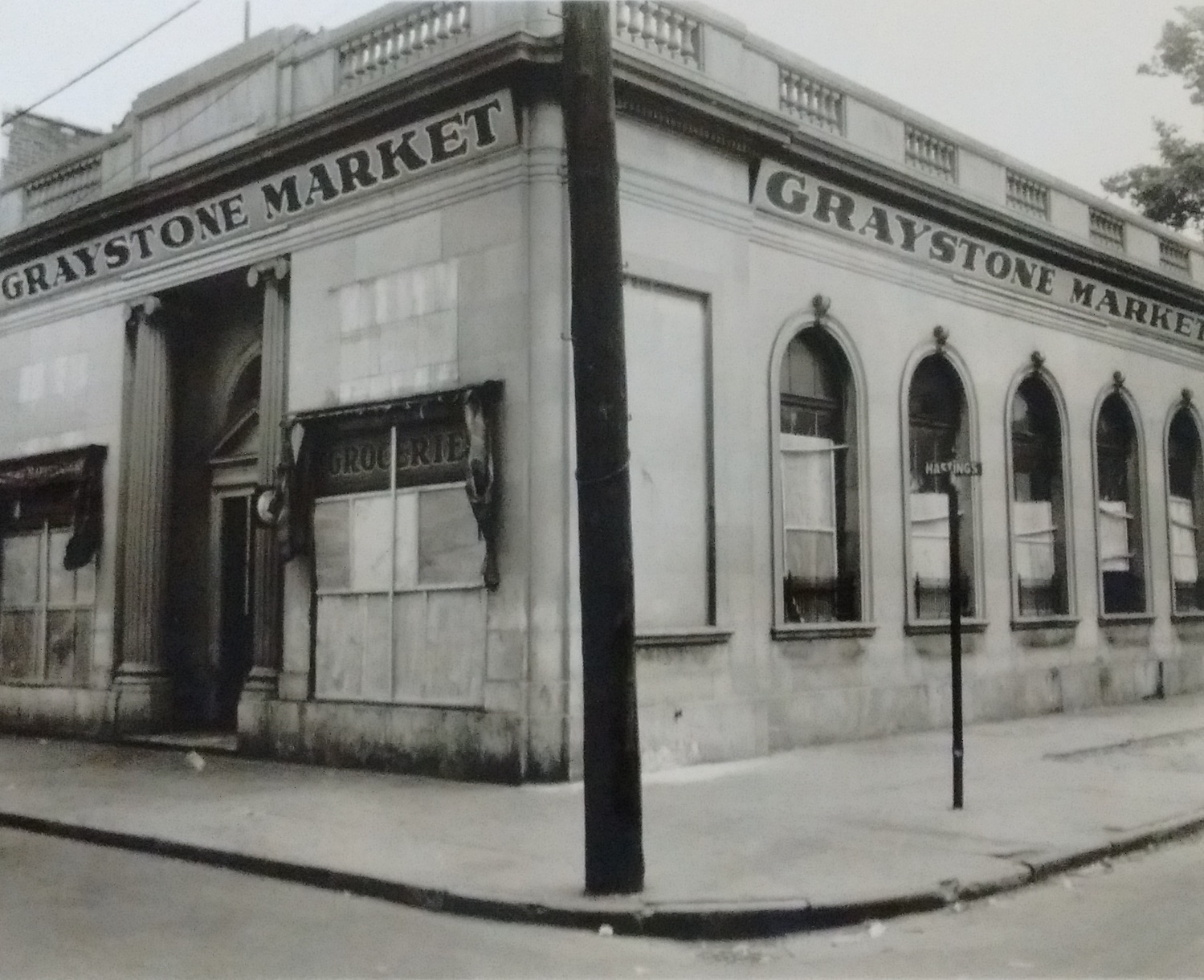

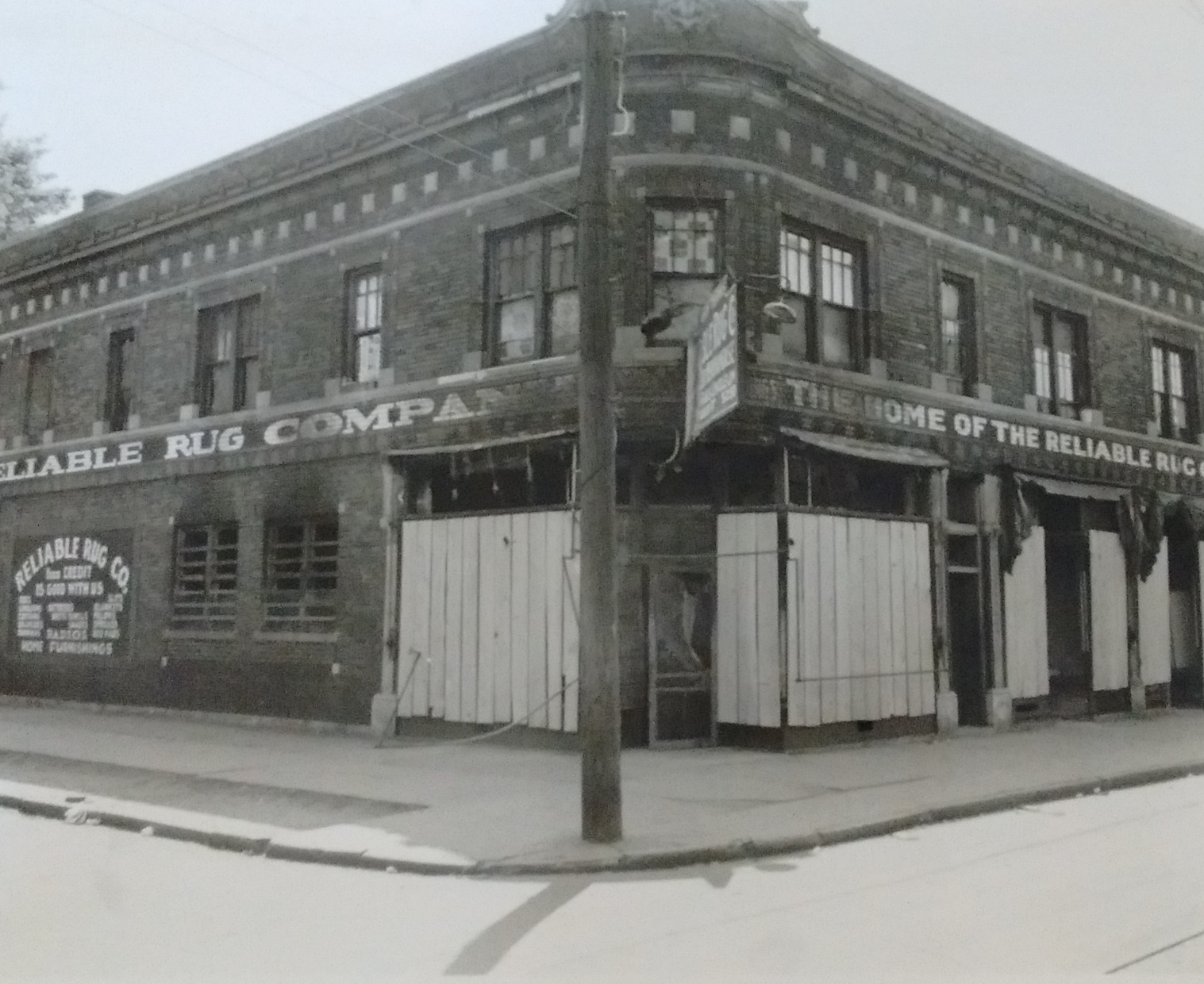

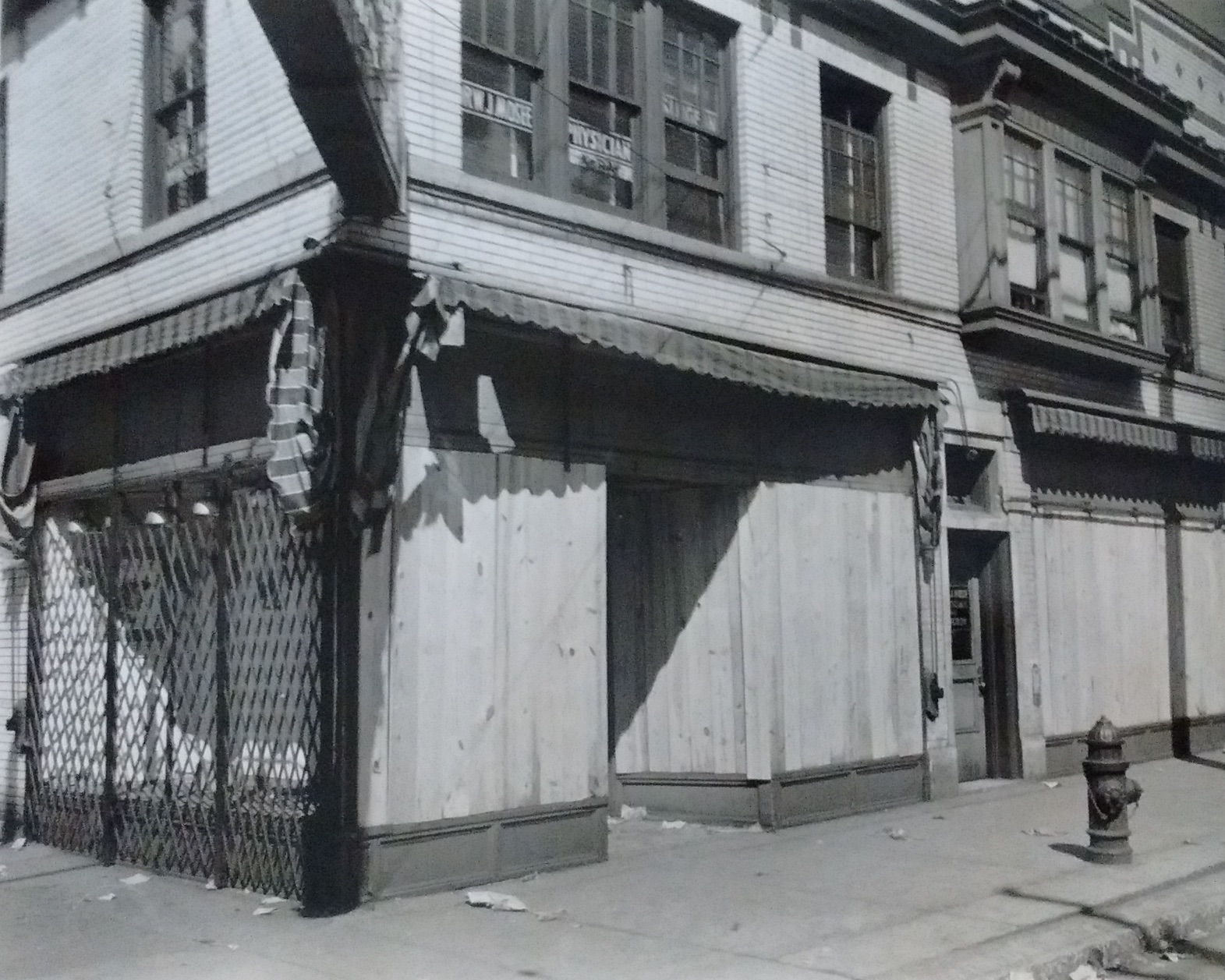

I also found that I could request a box that held a collection of photographic prints related to the 1943 disturbance. I requested this box again and again, especially interested in the photos of the vandalized businesses on Hastings Street. I eventually assembled a few folders of data on these photos, zooming in on them at home, cross-checking the details with old city directories, fire insurance maps, police reports, and newspaper text searches.

What I pieced together became a sort of guided tour heading north on Hastings Street, focusing on the vandalism, but in many cases constituting the only images of these buildings, businesses, or interiors to exist. I found myself lingering on these pictures, even though I knew a publisher would probably cut this detour from a book already too long.

Circumstances have changed—both for me, personally, and in Detroit in general—since my research began. These days, I live less than two blocks from old Hastings Street, where all that visibly remains of 1943 is perhaps a 1929 fire hydrant. I’ve often taken comfort that we still had a visual record of these buildings with stories to tell. It’s a treasure to know what was there once and what happened, despite the exploitative intentions of those who took the pictures.

Some other things haved happened in the past two decades. Three years ago, I had to make a special appointment to view materials, due to the pandemic. Also, the librarians had become a little less relaxed about viewing the collections in-person; instead, reassuring me that all of the images were available online. Although I didn’t think it was the case, I chose not to argue, only to insist that I wanted to examine the hard copies for the information on the back of the photos. I’m glad I did.

They alerted me I could not take photos of the 8 x 10 glossies anymore; I would have to photocopy them. Another change came in June 2021, when flooding overwhelmed Detroit’s sewer system. The basements of several Cultural Center institutions were flooded, including the sub-basements at the main library, where crews soon boxed up water-damaged materials from the repository.

This has added another layer of potential erasure to a story already about preserving the past. In this bumpy era of austerity and privatization, even the heavy hitters at the library can no longer guarantee that the history they hold is safe. Maybe it falls to a lone researcher, still working on the story after all these years, to share what he has found, presented with a mix of apology and permission.

Photos of Hastings Street—the main street of Black Detroit in the 1930s and 1940s—are in limited supply, since most of the street was plowed under for the Chrysler Expressway by the 1960s. But even before the bulldozers had their way with the thoroughfare, few of Detroit’s photographers took photos there. No doubt they chose what they perceived to be more appealing subjects. Cameramen usually only trained their lenses on Hastings Street under the guidance of sociologists or journalists on a public-spirited crusade.

One such occasion presented itself 80 years ago this month, the biggest “race riot” in the city’s history. At its climax, thousands of white Detroiters took over Woodward Avenue, where mobs of toughs attacked any Black person within reach while police largely watched it happen. Though much of the violence was captured in photographs, prosecutors often waited for victims to step forward before charging the white assailants caught on film.

In contrast, police, prosecutors, and mass media played up riot-related vandalism on Hastings Street. A cameraman wended his way up the riot-ravaged street for more than a mile, no doubt under police escort, photographing the wreckage, while merchants swept up broken glass and discarded packaging and filled their shattered windows with planks in those pre-plywood days.

These business owners, almost all of them white, many of them Jewish, were victims of a vile rumor that had exploded a few days earlier. It had all started on Sunday, June 20, when crowds leaving Belle Isle were caught up in a riot near the bridge to the island park. To some spectators, the main troublemakers seemed to be white sailors from the nearby naval armory. Black parkgoers certainly got the worst of that fight, from not just swabbies and bluecoats but from many of the white visitors to the park.

The trouble at the bridge was over by midnight. At that time, almost three miles away at the Forest Club, at the corner of East Forest and Hastings street, the entertainment was in full swing, with two red-hot acts: trailblazing Black Detroit society bandleader LeRoy Smith and “jump blues” pioneer Louis Jordan. The bill had attracted a crowd of about 700 Black patrons, most of them young. Not long after midnight, there was audible whispering on the dance floor. A man leaped onto the stage, grabbed the microphone, and made a startling announcement.

“There’s a riot at Belle Isle! The whites have killed a colored lady and baby. Thrown them over the bridge. Everybody get their hat and coat and come on! There is free transportation outside.”

Although every knowledgeable source—journalists, activists, police, politicians—later agreed that the announcement was false, the crowd did not know, and promptly went berserk, pouring out of the Forest Club and onto the street. Finding no cars waiting to take them and the streetcars not running to Belle Isle, the incensed throng began looking to even the score on the white-owned shops in their midst.

The intersection of East Forest and Hastings became ground zero for a new kind of urban disorder. Detroit and other U.S. cities had seen violent race riots before, in which white residents attacked Black neighborhoods, wounding and killing people in their homes and in their businesses. But in this instance, any white motorist or transit rider passing through the area was in immediate, mortal danger; Hastings Street was the scene of an uprising, a rebellion.

The white-owned businesses, closed for Sunday night, presented the most accessible targets to the outraged crowds. Despite their anger, in the wake of the announcement, the attack on the neighborhood stores was limited to vandalism. The stores were not set afire, nor were they looted. In the morning, however, as the stores lay open, their owners mostly unwilling to risk safeguarding them (something the police also neglected), that began to change. Though some residents had good relations with the business owners and tried to discourage looting, scores of Hastings Street businesses were emptied, particularly loan offices, beer gardens, and food stores. Only the arrival of troops of the United States Army restored order Monday night.

When the disorder subsided, there was ample justification for the overcooked dramatic treatment Hastings Street got in the white newspapers. According to the official report, businesses were looted on streets in several east side areas, from downtown up through the Oakland Avenue extension. The FBI counted 292 places of business in these areas with their storefronts smashed in. But they were all distant runners-up to Hastings, the runaway top street, with 113 reports of looting from downtown out to Medbury.

The shock was real enough to Detroit’s white newsmen, who had been denied access to Black neighborhoods until the Army’s arrival. The street was covered in discarded and trampled goods and packing, with clothes fluttering from broken windows, and steel grills torn and twisted off storefronts. There was so much broken glass as to be ankle-deep in some places. Several Black Detroiters were treated for injuries from storefront glass, and the first Black fatality of the day was Samuel Johnson, 33, who died of blood loss after a piece of broken glass fell on his left upper leg, severing a major artery. City workers would not begin the job of sweeping up the tons of debris and broken glass for another two days.

Downtown, having been dominated by white rioters and white-owned businesses, saw limited vandalism, but beginning at Vernor Highway and moving north, the damage grew worse in the first few blocks. The Detroit Public Library’s Burton Collection holds a photographic record of the damage along Hastings, and it begins about six blocks north of Vernor. It is a heady experience viewing the images. At the time, the photographs were doubtlessly intended to play up the alleged criminal tendencies of inner-city Black Detroit. But at a remove of 80 years, the contemporary viewer can’t help but be struck by the prewar architecture, the unbroken streetwall, the quaint tin ads, bygone street names, product brands lost and living—and, behind it all, the churn of World War II raging overseas.

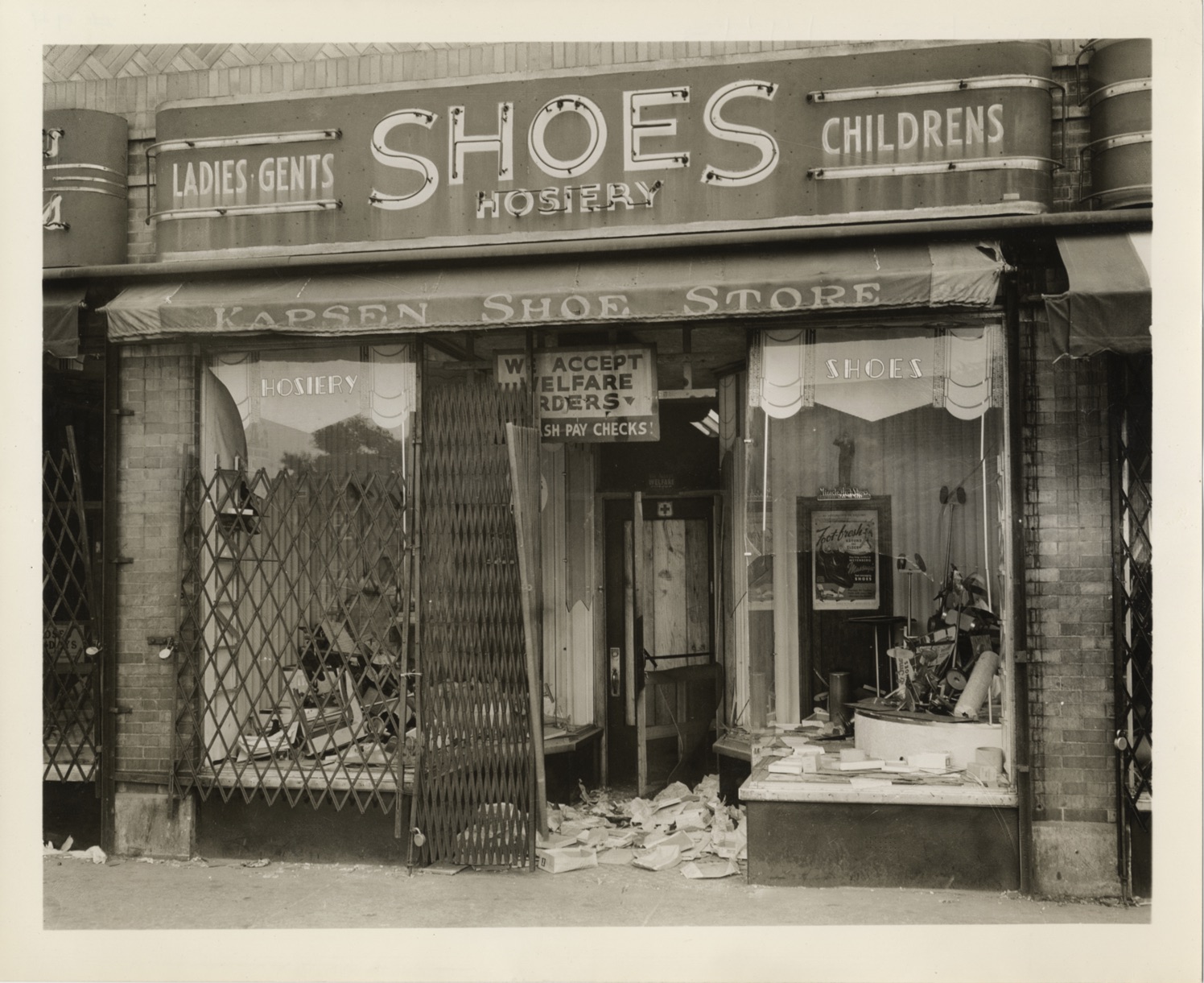

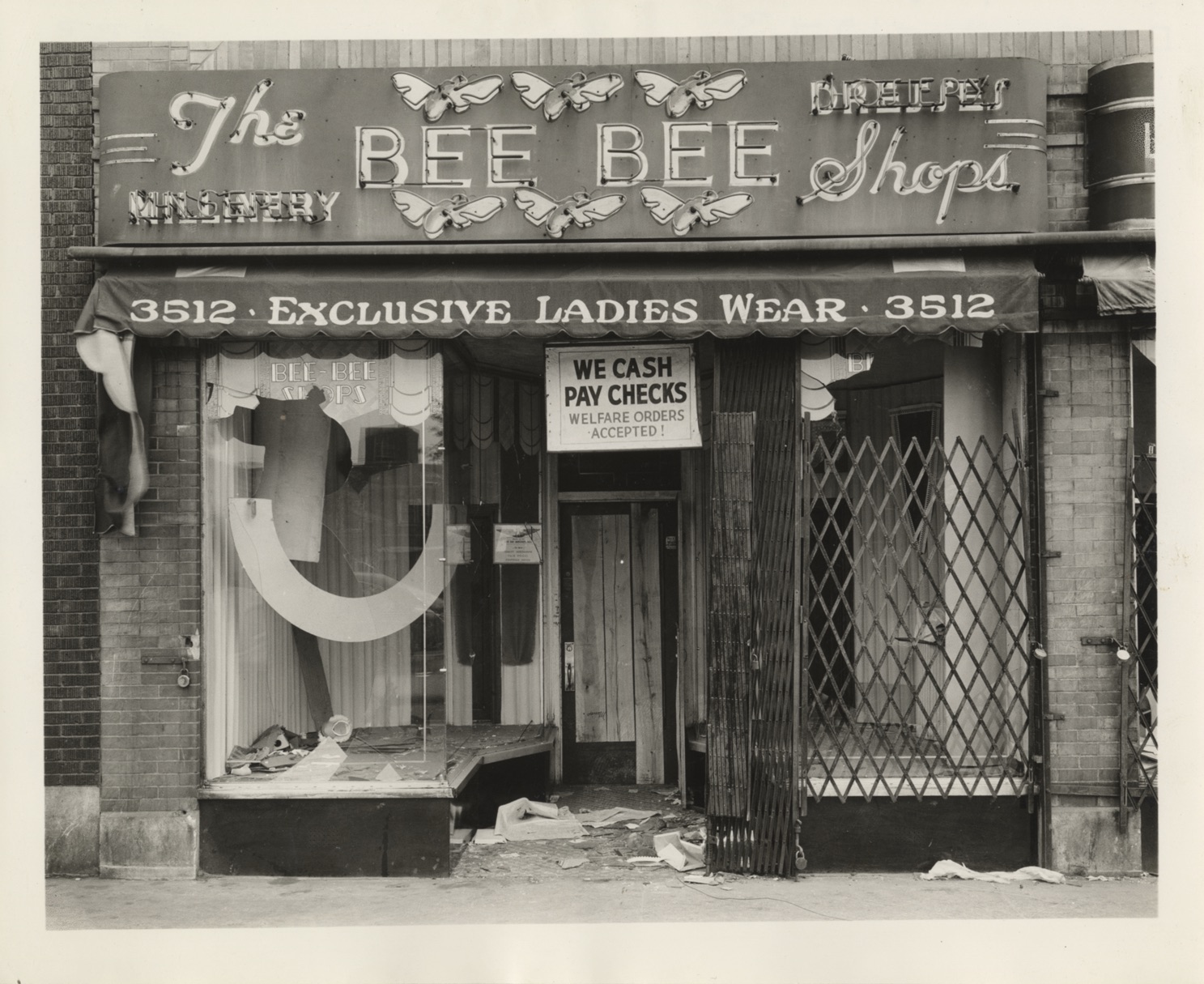

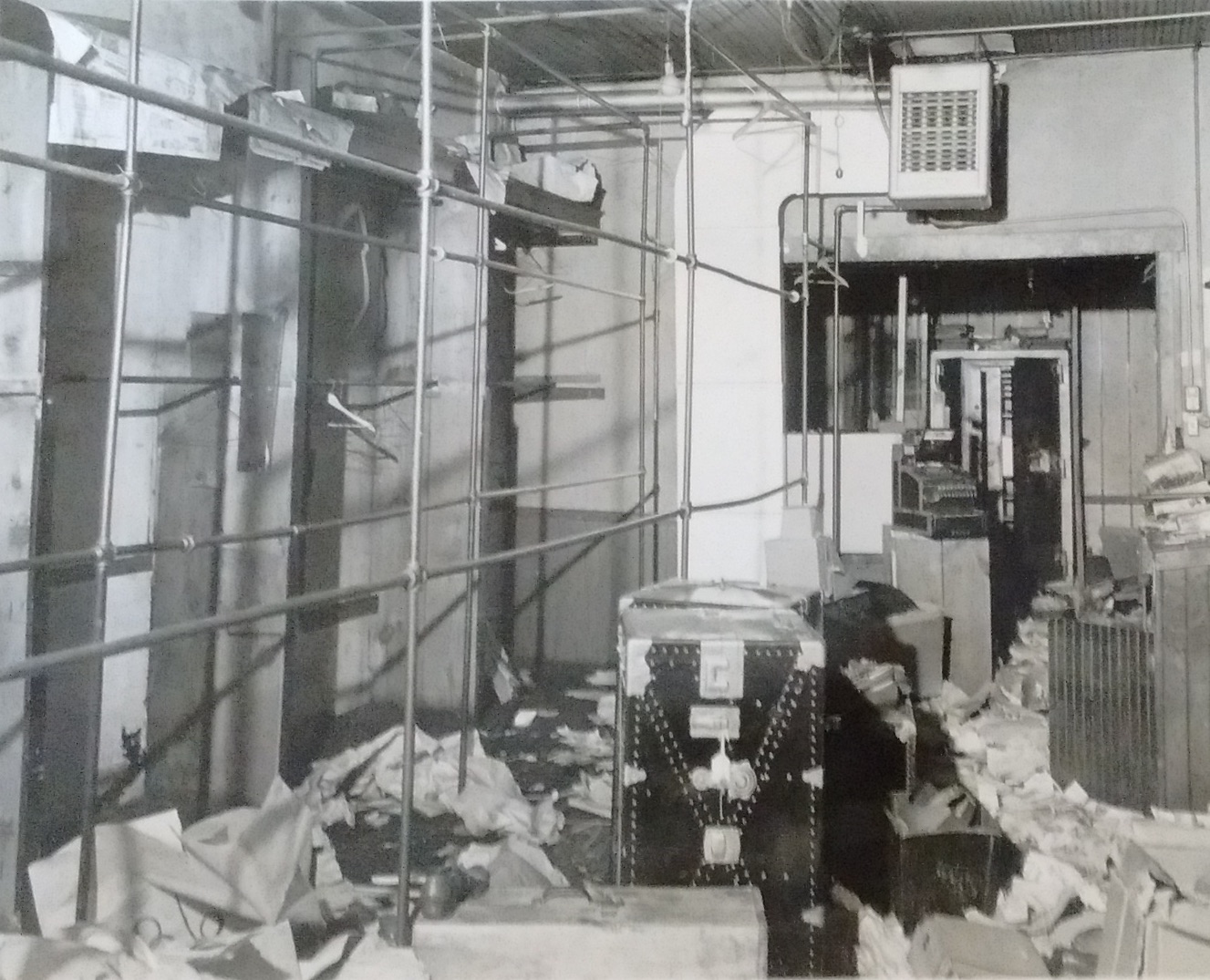

The storefronts on the northeast corner of Eliot and Hastings had their windows smashed and their display cases emptied. Inside, broken glass covered the floor of Wiener’s Smart Mens Wear. Next door, empty shoe boxes carpeted the entrance of the Kapsen Shoe Store. The next storefront, one of the Bee Bee Shops owned by Bernard Sidran, had been smashed open and the store’s “exclusive ladies wear” raided. The door was covered with boards; inside, it was practically denuded of wares, with only eerie head and leg mannequins remaining.

A block north, at the corner of Rowena (now Mack Avenue), a pawnbroker’s shop run by Morris Wasserman, the Morris Loan Office, seemed to be almost a total loss. Though the metal gates were back up, the establishment had few of the goods—watches, jewelry, suits, overcoats, radios, luggage—advertised on its brick storefront. Everything was gone except the cash register, the gas blowers, and a sign reading “Please Bring Your Own Hanger.” The cabinetry had been smashed open, and even the safe in the back was jimmied and ajar.

Near neighbor Greenberg’s Department Store had the bad luck to be adjacent to a pawnshop. The interior was a ransacked shambles of empty shelves, open drawers, and tipped-over mannequin heads. Police listed losses totaling $8,000 (almost $140,000 in 2023 dollars). Up around Brady, the Ace Men’s Shop, “Home of the New Yorker Hat,” had been boarded up, with claims totaling $1,500. Across Illinois, Sally DeRouen’s Sally Dee Shop, located on the ground floor of a weathered, slat-faced old 19th century building, seemed robbed of everything but two mannequin heads atop high shelves, their headgear still on.

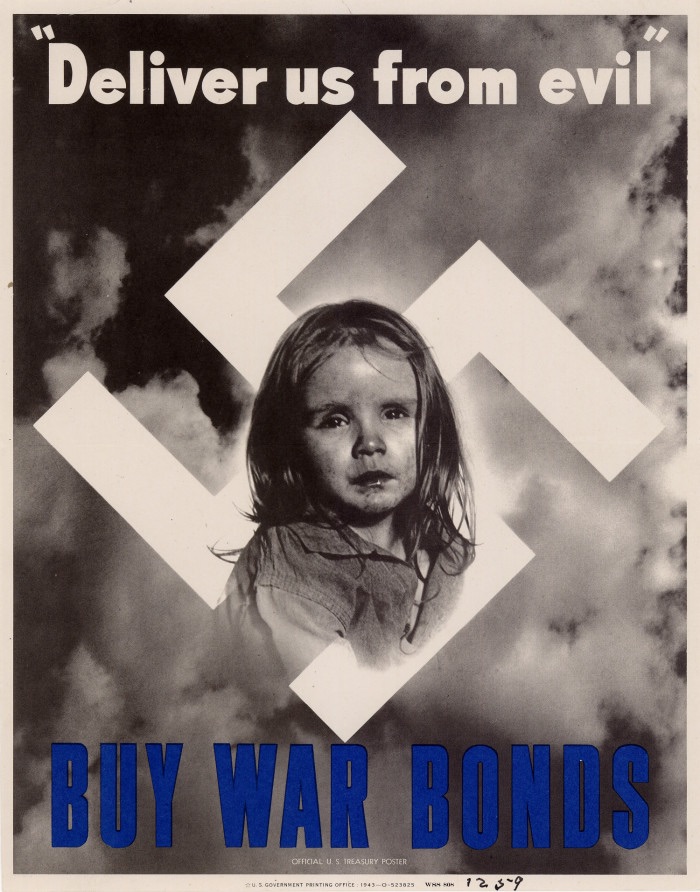

North of Leland, Paul’s Cut Rate Drug had its windows shattered and was looted, as was near neighbor Joe’s Tap Room. The beer garden, run by Joseph Chafetz, was a former savings bank, bearing medallions, corbeled cornices, and a grand arched entry with decorative trim and a scroll keystone. The interior presented an eerie scene, not a bottle of liquor on the shelves, the calendar frozen on June 20, and a “Deliver Us From Evil” war bonds poster, featuring the head and shoulders of a weeping European girl, photographed by Harriet Nadeau, framed by ominous clouds and a white swastika.

Across Willis, Canfield Cut Rate Drugs had been looted but boarded up securely, and across Forest “Louie’s Quality Market” also had boards going up over its broken windows. In this area, where the false rumor had stoked such rage the night before, witnesses said shops were more likely to suffer smashed furnishings and shattered woodwork. Just south of Warren, what was probably a dress shop had its clothes tossed helter-skelter, while a few mannequin heads looked on. If only the mannequin heads often remained, it was because the full-body dummies, usually modeled with Caucasian features, were often put to provocative purposes with potent political meaning. A Detroit News reporter said they were “sprawled grotesquely or over the curbing or leaned against the buildings,” or “hanging from store signs [and] shattered door frames.”1 The wiring of a broken utility post was used to craft a hang-noose for one of them.

On the other side of Warren, at Nat’s Loan Office, another pawnbroker’s shop, perhaps two-dozen blazers and overcoats remained after the 90-degree day of looting. In one photo, the racks are empty. Just as at Morris Loans, Nat’s vault had been opened, the door bearing the marks and bends of a pry bar.

Up at Theodore, Boesky’s Cut Rate Drugs had display windows planked up, with a view inside of raided cases, stripped Medico pipe and filter displays, and empty bottles and cigar cases littering its small lunch counter. The Boesky family owned a few drug stores and eateries in the area, but would be better known for scion Ivan Boesky: Only 6 years old at the time these photos were taken, in the 1980s he’d become an infamous white-collar criminal, allegedly the inspiration for Gordon Gekko in the film Wall Street. Note also the shingle and window lettering on Boesky’s exterior for Black physician J.H. Sparks. Black doctors often occupied second-floor offices on Hastings Street. It’s likely the last shot of his office, as the Texas-born Sparks would die the next month.

Across the street, the shoe shop of Louis Bovitz had broken glass and torn awnings. The damage didn’t scare Bovitz away; four years later, he was found mortally wounded inside the shop. Just up Hastings, the Parker Brothers shop was boarded up tight, with gates over the wood for good measure, having involuntarily lived up to its boast of providing “shoes for the entire family.” Parker Brothers would claim $4,000 (almost $70,000 in 2023 dollars) in losses.

The Graystone Super Market north of Farnsworth was a grand building, another former bank, faced with stone, topped with balustrades, and sporting an entrance not just flanked with actual ionic pillars, but topped with both an arch and a pediment. Looters seemed most interested in owner Nathan Siegel’s meat counter, which was cleaned out entirely, as was the stock of resident fruit dealer David Rose, save a crib full of walnuts. Yet many of the jars and boxes of food products remained untouched, as seen in a photo that shows the market’s interior, with light falling in from the arched windows, a Vernor’s gnome leering over the scene from a wall sign.

Up at the intersection of Frederick, the Reliable Rug Co., a hulking two-story brick building rounded on the corner, was a scene of boarded windows and retracted canvas awnings. Inside, it was thoroughly trashed, not so much out of any hunger for carpeting, but because it offered radios and other home furnishings on credit. In fact, looters often targeted the records in lay-away shops, making it difficult for those owing money to be held to account. Official value lost amounted to $1,500 (more than $26,000 in 2023 dollars).

The wreckage was almost as bad across the street at the Golden Bell Bar, run by Harry Brandt and Nathan Silvers. Immortalized in the Detroit Count’s “Hastings Street Opera” as “the onliest place … you have to shovel the sawdust off the floor ’fore you can buy yourself a drink,” it was now looted of all drink, and more than a shovel would be required to get past the wreckage to the bar. Busted bentwood chairs covered the floor, and the central panel of the Wurlitzer Model 850 jukebox appeared to have been smashed. The owners would claim $2,000 in damages.

Across the street from Graystone was a lesson in how white shop owners were targeted and Black businesses were spared. The shoe store of Philip Eisenstadt had its broken windows covered in planks of wood, whereas nobody seemed to have even thrown a rock through the upper floor window of Black surgeon and physician Dr. W.J. Mosee. This was not unusual.

The police record shows that looters did, by and large, resist looting certain establishments. For example, at the riot’s end, 17 Black-owned drugstores had not been vandalized, and another had suffered only a broken window, but no looting. Meanwhile, 27 white-owned drugstores had been smashed, ransacked, and robbed. In case any vandals missed the point, the word “COLORED” became a common sight, appearing in chalk and fresh paint on the windows of Black-owned establishments.

Some commentators, such as Philip A. Adler, claimed to see in the selective looting a manifestation of anti-Semitism. Writing for The Detroit News at that time, Adler stated, “About 80 per cent of all stores for about two miles of Hastings Street were looted. And … it would be a safe guess that about 80 per cent of the ruined stores were Jewish.”2 Yet it is likely that Jewish shop owners were not discriminated against for their heritage or religion so much as they were viewed by many Black residents as whites, and as outsider profiteers. (That said, their creed would play a role in the way their claims would be handled by the largely Anglo-Saxon authorities.)

Endnotes

1. “Paradise Valley in Ruins, but Traffic Flows Again,” Detroit News, June 22, 1943, 1, 4.

2. Philip A. Adler, “Anti-Semitism Cited as a Prelude to Riot,” Detroit News, June 29, 1943, 7.

Images courtesy the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library. All rights reserved.

Michael Jackman spent fifteen years at Detroit’s Metro Times, where he started as copy editor and worked his way up to senior editor. He is in the process of completing his nonfiction book about Detroit in the 1940s.

Also from this series, by Michael Jackman

Men of the Cloth, Men of Capital

A Case Study of Northwestern High School

View next: SIM ER by John Bennett