Imaginary Solutions

An Introduction to the Ridgeway Collective

By Cary Loren

As to the action that is about to begin, it takes place in Poland—which is to say, nowhere.

–Alfred Jarry, Ubu Roi

The absurdist comedy Ubu Roi is a mixture of dark humor, nihilism, symbolism, and rebellion. Written by Alfred Jarry, a fifteen-year-old student in the late nineteenth century, it can be considered a raw parody of Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Hamlet. Jarry first directed and performed his play as a marionette show in his home, with fellow classmates. He saw a bleak and absurd future, a world turning toward fascism and totalitarian rule, through the eyes of his main character Père Ubu, a grotesque, bloated, savage man-child.

Ubu Roi was a shot across the bow of the twentieth century. As an expanded live play with actors, it debuted in 1896 in Paris, and when the curtain closed a riot broke out. The piece would become a proto-text for Dada, Surrealism, Futurism, Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty, the work of Samuel Beckett, and Julien Beck’s Living Theater. Jarry’s subsequent writing attacked tradition, religion, reason, art, and academics, becoming a philosophy he called “the science of imaginary solutions,” coining it “pataphysics,” which quietly altered the trajectory of art history, literary poetics, and the visual taste and styles of the twentieth century. Pataphysics was absorbed into Dada and inspired other anti-art systems that followed, including Fluxus, performance art, and mail art.

Dada was formed by a group of international artists who had escaped the terrors of World War One. It was an anti-social, anti-bourgeois, and anti-capitalist movement with origins at Cabaret Voltaire in 1916, a bar and performance space in Zürich, Switzerland. Tristan Tzara, one of the primary founders of Dada, praised Jarry for his opposition to bourgeois society and for delivering low humor into poetic legitimacy, subverting time with the unexpected and giving the “language of absurdity and surprise” a home in the twentieth century.1

In 1974, Dada found its way inside working-class metro Detroit, when artists and poets who were students at Macomb County Community College [MCCC] formed a collective known as Ridgeway. Its surfacing made sense at the time, in the aftermath of Vietnam, the end of the psychedelic sixties, and the emergence of punk. The members of Ridgeway applied Dada to their art in sincere and absurd ways: as a game, in the same way Jean Baudrillard called pataphysics a game that was “far more dastardly than any other.”

Ridgeway projects included performances, exhibitions, poetry readings, film screenings, political actions, mail art, and small press printing. Their name came from a small off-campus house located at 22421 Ridgeway St., between Jefferson and Mack in St. Clair Shores, a city near Detroit. The house was shared by artist Carl Aniel and Larry Wilson, a Canadian organizer and planner for the group. Core members also included artist Jeff Ensroth, photographer and group archivist Gregory Hallock, poet M.L. Liebler, and poet Donna M. Penner (formerly Pici). Poet John M. Marino and artist-cartoonist Carole Sobocinski were also in Ridgeway but lost touch with the group. Although organized as a collective, members were free to create and contribute on their own. Ridgeway was an artistic “secret society” using comedy, farce, and Dada.

Untitled ray-o-gram, Greg Hallock

Untitled ray-o-gram, Greg HallockThe Gang That Couldn’t Teach Straight

Macomb County is located northeast of Detroit and comprises the cities of Sterling Heights, Warren, Mount Clemens, St. Clair Shores, and Roseville. It has recently been characterized as the home of our country’s angry white men and women, a demographic that includes many of the blue-collar auto workers who helped elect Trump in the 2016 election, though it’s the same county that elected President Obama twice. The county is a closely monitored “battleground,” and yet suburban angst was apparent even in the sixties with the absurdist fringe rockers of Mount Clemens: The Früt, a group of mad stoners who invented deconstructionist rock ’n’ roll.

Macomb County Community College in the early seventies was a crucible of radical education and thinking. Many of the faculty were recent graduates of Wayne State University with strong connections to Detroit’s creative community. Faculty included poets Lawrence (Larry) Pike and Bill Cox, who headed the English department and ran Red Hanrahan Press, film studies professor Phil Barrons, and artists David Barr and Jim Pallas.

“Macomb was the new school in town, with very cheap tuition—maybe under ten dollars per credit hour,” recalls former student Carl Aniel, a member of the Ridgeway collective.

“One of my mentors in the English department, Arthur Ritas, showed me an internal bulletin called ‘The Gang That Couldn’t Teach Straight,’ and it detailed various methods to engage students who lacked basic skills or mindsets for college … Teachers were of that ilk, trying to really make a difference in their students’ lives.” Aniel was a projectionist on campus for screenings of Blood of the Condor, A Luta Continua, and other films about native resistance and rebellion. Mentored by faculty, he later went on to study filmmaking at Columbia College.

“Macomb [College] was a hotbed of creativity back then,” recalls Detroit poet M.L. Liebler, a fellow member of the collective. “We had John Cage in residence, Ant Farm, Bukowski visited often, Michael Horowitz from the U.K., and all the usual suspects: Allen Ginsberg, Robert Creeley, Ed Sanders and many more.” The visiting artist program at the college even inspired a similar series known as “Lines” at the Detroit Institute of Arts, led by Detroit poet and educator George Tysh.

John Cage lectures at Macomb County Community College

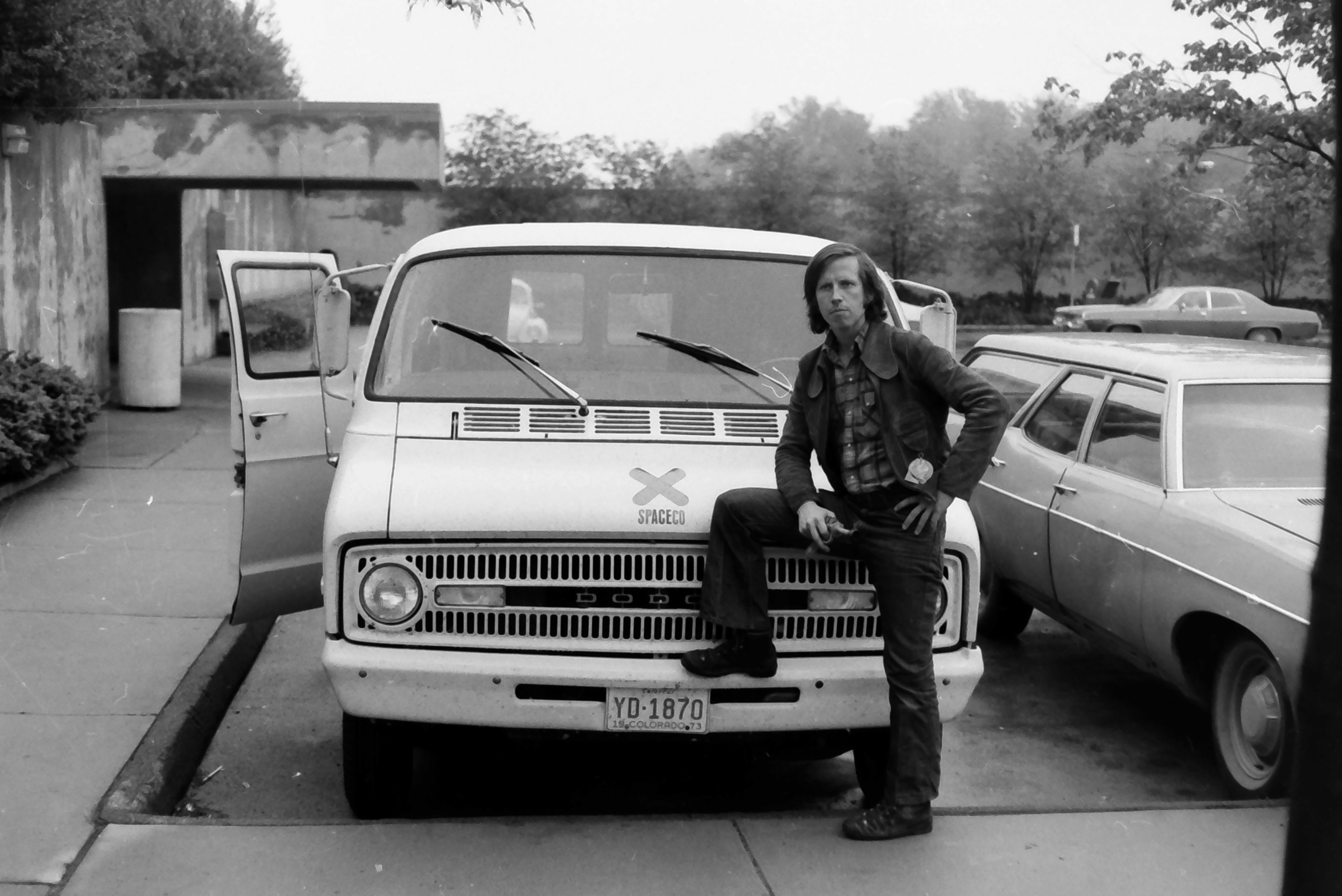

Dana Atchley, a visiting artist at Macomb County Community College

Macomb faculty member Jim Pallas, a pioneer in the fields of electronic arts, was a major influence on the collective. “With his beard, glasses, and enthusiasm, he always reminded me of Leon Trotsky,” Aniel says. Pallas’s offbeat humor made him a beloved figure. According to one student, he taught an entire semester wearing a Colonel Sanders mask, although he denies it.

Dana Atchley, a mail artist also known as Ace Space who drove cross-country in the late sixties documenting artists and art collectives, was a guest invited by Pallas. The members of Ridgway learned life lessons at Macomb, connecting with the human and personal elements of artmaking, including intimate forms of production, such as the humble simplicity of handmade postcards, inspired in part by Atchley and artist Lowell Darling, who also visited campus.

“I don’t know who initiated it, but we all started sending mail art postcards to each other,” recounts Aniel. Ridgeway postcards were gems of Dada, surreal art, and humor. The early seventies was an explosive time of mail art exhibitions and activity. Ridgeway took an opposite approach and distributed their cards in a closed network to one another. The cards are funny, political, and irreverently punchy visual art—a slice of portable Dada. [View the image gallery within this dossier.]

Most Ridgeway postcards were the traditional type found in souvenir shops or museums. They were altered with glued-on news clippings, drawings, and other additions. Some cards were photographic (made by Hallock) or collage, created with vintage clippings sandwiched into a few or more layers over cardboard. An excellent archive of this work has been preserved by Hallock. A few cards have written instructions, poetry, or ideas for Ridgeway on Tour exhibitions and projects. In one card sent to Hallock from 1975, Aniel wrote:

I really want to get some work done on our book. Coleman’s book is finished: Leonid—it looks okay. M.L. is done too—but maybe you already know that. I’m retyping Earthwalkers, and Larry’s working on graphics. I want to do a movie called Crums Along the Mohawk—the story of a writer who drowns entangled in a stack of deck chairs. Of course, there will be the proper amount of innuendos and 5th columnists and cops on the take.

The Gang That Didn’t Art Straight

Ridgeway added publishing, bookmaking, and performance art to their practice, connecting them to public and collective forms of creating art. A more surrealist vibe appeared in the 1979 dual poetry collection Island From Fear and Critical Chairs by Carl Aniel and Gregory Hallock. This was also the first book published by Ridgeway under the direction of the Bureau of Surrealist Research, which signaled a change of direction. Hallock explains:

“The early style of Ridgeway was very Dada/Fluxus. We were all about the jokes and we were laughing our asses off. After the Dada thing, everyone went through a transition. We went a little deeper when Carl and I did a book together in the last period of Ridgeway, around 1979. We were getting more into Surrealism. All of my poems on that book were done by keeping myself awake for 48 hours and then writing down whatever came to mind. I stole the idea from Robert Desnos, the surrealist poet who talked in his sleep.”

Ridgeway Press books were folded in half sheets of 8.5 by 11-inch paper, staple-bound, and made on no budget, with help from conspirators on Macomb’s faculty.

“Phil Barrons gave us the paper for the book covers,” says Aniel. “He would also lend us pass cards for the print room.” Ridgeway members would sneak into the copy machine room, photocopying booklets one page at a time to avoid detection.

Aniel and Wilson would later collate and assemble the booklets at the Ridgeway house and produce them in numbers of fifty copies or less. “I’ve never thought of Ridgeway Press as something Carl and I started,” Wilson says. “I just rented a house and needed someone to split the rent with. Carl was the one putting together poetry collections and was the force behind press activities. I may have helped with folding and stapling, but he attracted a wide variety of people. I once described him as having these various groups of friends that orbited around him, and at various times the orbits of those groups intersected.”

Aniel made Dada signs and experimental art for Ridgeway with his small Kresge letterpress. He explains:

“My cousin worked at the Kresge store in Roseville, and they were throwing out their sign press. It was used for making sale signs and they had just received a computer, so I was able to pick it up for nothing.

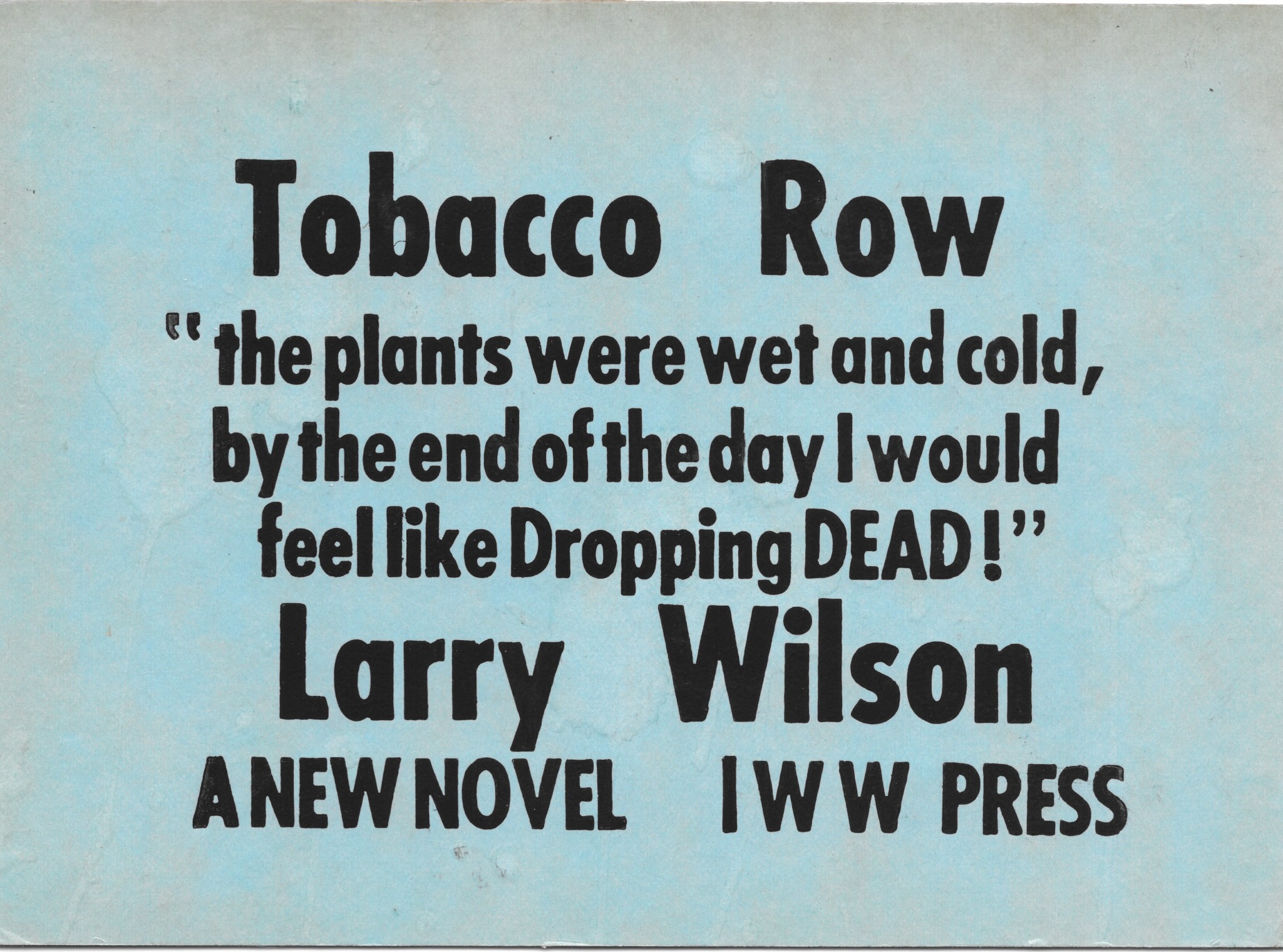

“It had a metal bed, maybe twelve inches wide, twenty-four inches long, and there was a roller that moved above the bed on a rail, so you could pull this roller back and forth over whatever you placed down on the bed. I designed and printed a bunch of Ridgeway material, party fliers, and fake announcements, like Tobacco Row by Larry Wilson. I had found some high school essay Larry had written, which was very uninteresting except for one line, which went on the card, “the plants were wet and cold, by the end of the day I would feel like dropping dead”—I hadn’t read Steinbeck until later, but that never stopped a parody.

“Greg turned me onto Man Ray, and showed me his Ray-o-grams, which led me placing objects under the paper of the sign press. These were monoprints we’d show at Ridgeway exhibitions.”

Gregory Hallock introduced the Dada and surrealist aesthetics to the group and documented Ridgeway activities in photographs. Aniel amplified their program with sardonic humor, plotting events and designing and printing announcements and Ridgeway books with help from Larry Wilson. Events and exhibitions often ended up destroyed, raided, or shut down by the police. Aniel recalled the humorous spirit of Ridgeway:

“We were the aftermath of World War One Dada. We were in this semi-shithole, so why not entertain ourselves? Let’s turn it into something worth living for. Let’s laugh at everything, particularly ourselves. If we can’t laugh at ourselves, who can we laugh at? I think this group was the gang I didn’t know I was looking for.”

When Aniel and Wilson left the Detroit area in 1980, the group disbanded and Liebler took over Ridgeway Press, publishing poetry, including John Sinclair’s We Just Change the Beat (1987) which was reprinted three times, as well as fiction and cross-genre work, like the dense mathematical and cosmic music treatise by Detroit musician, composer, and writer Faruq Z. Bey, Toward A ‘Ratio’nal Aesthetic (1989), republished by Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (2012).

Nearly a half-century since the Ridgeway collective began, they’re still exploring pataphysics. The close bonds they built from years ago have continued. They’ve shared summer vacations and now convene regularly online. Dada Zilch (Carl Aniel) edits and distributes 101 Mirages, a monthly email of unusual art documents and Ridgeway updates.

The group left behind many unrealized projects—another connection to original Dada, which embraced negation and failure. Tzara wrote: “And so Dada was born of a need for independence, of a distrust toward unity. Those who are with us preserve their freedom. We recognize no theory ... Let each man proclaim: there is great negative work of destruction to be accomplished. We must sweep and clean.”2

Read next: “Normals Unlimited and the Early Years, The Ridgeway Collective Interviews Itself,” inside Make Room for Dada: A Dossier on the Ridgeway Collective by Cary Loren

If you’d like to subscribe to 101 Mirages, send a request to RidgewayArtsCollective@gmail.com

Cary Loren is an artist and member of Destroy All Monsters. He is co-owner of Book Beat, an independent book shop in Oak Park, Michigan.

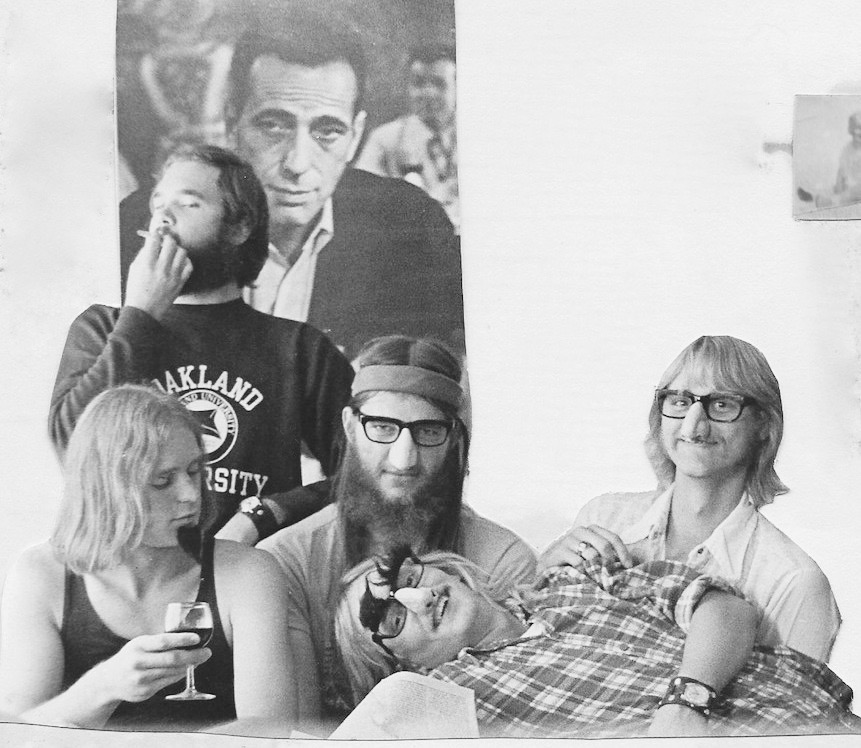

Lead image: Standing: M.L. Liebler, seated: Jeff Ensroth, Carl Aniel, Larry Wilson, Greg Hallock.

All images ©Gregory Hallock 1975/2023

Endnotes

1. Elmer Peterson, Tristan Tzara (Rutgers University, 1971) pp. 95-96. In Peterson’s book Tzara explains Jarry’s contributions to Dada in his essay: “Essai sur la Situation de la Poésie”

2. Lucy R. Lippard, Ed., Dadas on Art (Prentice Hall, 1971) pp. 15, 19, quoting Tristan Tzara’s “Dada Manifesto, 1918”