The Art & Writing of Cay Bahnmiller

By Cary Loren

An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to make you realize the doom and glory of knowing who you are and what you are.

–James Baldwin

Detroit artist Cay Antoinette Bahnmiller (1955-2007) was a supernatural consciousness, a person of high sensitivity, writing “a new biography of Nature” in her paintings. She painted with unwavering conviction and confidence—looking deep into the world and within herself. Her journey through symbols and language was a mind unchained, producing a body of work that was dramatic, unique, frightening, neurotic, and beautiful in its surface complexity and intellectual depth.

She earned her BFA summa cum laude in 1976 from the School of Architecture and Design at University of Michigan, then traveled west around the country and came to settle in Detroit two years later. Bahnmiller was an exotic voice in a city unsympathetic to the attention she gave it—a voice that went mostly unheard and ignored. Her art matured greatly at a time when artists began scrambling to create a web presence and build up their “brand” with fandom or risk irrelevancy. She made her work in furies, clearing away an inner life and space for art to exist. She used coded language in her paintings, rewriting abstraction, embedding her canvas with allusions, philosophy, and nihilism. Confident and forceful, she often recalled artworks from galleries and collectors, re-working, adding onto, and disintegrating them. She demanded a higher awareness and involvement from her audience and collectors, a viewpoint uncommon in visual artists.

Subverting her own success at almost every turn, the artist’s controlled application of negation was based in language and philosophy and she developed a 30-year practice in sympathetic connection with her own pathology. Her work was a chronicle of observation and reading, with painting at its core.

Bahnmiller was the last bohemian painter at a time when the cellphone began its monopoly on our time and awareness. “Painting is my most serious life’s work,” she said, “and my commitment to my work has always been unwavering. Many times, this has meant certain hardships and decisions that determine the very basics of how one lives. The decision to be a painter was one I never made; however, I always have ‘made’ things and believe it is not a choice or a becoming; it is what one always was and is.”1

She had an infectious laugh and relaxed by taking walks to Bird Town in Chinatown on Cass Avenue to hear the parrot curse. She had a collection of antique wooden rolling pins, postcards, old broken dolls, and toys. She was a bricoleur and scavenged from the streets and thrift shops.

Bahnmiller painted the covers of her favorite books and talked on the telephone nonstop, calling friends to discuss life and gossip. Sometime in the ’90s the calls came later at night, one-way conversations that were therapeutic, airing out grievances and feelings of distress. Several years before her death, she began giving away books, rolling pins, artwork, and artifacts.

Paint was in her flesh and blood, literally. She adored eating healthy foods yet mixed toxic paints directly onto her left hand, using it as a palette, later seeing doctors to help her overcome the pin-pricking pain, and nerve and muscle damage. Her palette was the color and light of Detroit.

“My perception in painting is enhanced by executing this work in the archeological ruin of Detroit,” she wrote, “a city steeped in sedimentation of light, or as architect Louis Kahn wrote, ‘spent material.’ The stark absence of an ‘outer’ world necessitates the imaging of an interior—Dickinson’s ‘Bright Absentee,’”2 an allusion to the private life of bees and the beehive. The dream gardens she tended were both real and imagined: Belle Isle, where she’d often stroll with her dog Lilli, the dense English cottage garden of her friend Robert Lebow, and her Park Street home blooming with wildflowers.

She credits Emerson’s transcendentalist movement for inspiring her view of nature as spirituality. Her writing is filled with descriptions of nature walks, poetry, flowers, and gardens. And the bee—a creator and servant of nature and symbol of eternal hope—became emblematic for her.

In the mid-’80s, Bahnmiller was hired to develop a seminar at the Detroit Institute of Arts by George Tysh, who ran the LINES series on new writing. In the classroom, she brought together her favorite subjects, literature and philosophy, that held important guideposts for her painting.

“I had a professional relationship with Cay at the DIA,” Tysh recounts. “I asked her to do a course for a workshop series on reading, language, and text—and it was one of the more sophisticated and theoretical classes we did. She got people to think about language and reading in a new way. I sat in on that class because I was fascinated by what she was doing.”3

Although she had the support of such esteemed professionals as urban planner Charles A. Blessing, director of city planning in Detroit from 1953 to 1977,4 as well as Mary Jane Jacob, curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago,5 and MaryAnn Wilkinson, curator at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Bahnmiller’s grant money and art sales were barely enough to live on. She made friendships with many collectors, some of whom remained close for years, and others turned sour. Bahnmiller set no boundaries or limits. She would badger collectors and, in one case, broke into a friend’s home, crawling through a window to steal back her artwork and correspondence. In a letter, she spells out her commitment and overview of the art world:

“I’m so tired of all these art wannabees, hanger oners, onlooker prognosticators, bookies, turnkey mentalities. This is my life, not [a] recreation. It’s all or nothing, For starters, there are maybe a half dozen people doing ground-breaking work today in the visual arts. Few people with original vision. It’s not entertainment, it comes out of survival. I sure don’t see any Medicis, do you? It’s like an oil glutted economy saying to Biafra, oh I am such a big shot, good person I give a can of tuna, I beeeegggg poisson. To stand around and see your culture die, or the arts is so boring so quick. […] If you had any idea about my urgency as an artist, you would see that I see my life already accomplished by the fact of WHAT I MAKE WITH MY HANDS AND SEE WITH MY EYES, MY GREAT GIFT WITH LANGUAGE, SPACE FORM ETC.”6

Bahnmiller shut down a solo show for herself on opening day. She sabotaged exhibitions if in her mind it meant compromising her principles. If she had regrets, and there were many, sincere apologies would follow in calls or letters. If not, she could hold a grudge for years. From another letter to a close friend:

“I realize I’ve been quite a powder keg with a lot of people. I think it’s fair to say I’ve had perhaps way too many obstacles, and we all have a breaking point and I met mine. I feel tremendous remorse that I could be that unkind to one of the gentlest people I’ve known. So how to go forward, when I’ll always feel so badly about my behavior?”7

Her talents were bound up with dark emotional, social, and physical forces she couldn’t control. Her love of urban landscapes offered inspiration yet tore her apart. She came from a wealthy family but lived in a condition of poverty by choice, seeking survival on her own terms. Unable to shake off mental demons, Bahnmiller dealt with her condition through pills and alcohol—a self-medicating combination that consumed her by suicide in 2007.

Her father Richard Bahnmiller, a top executive with Ford Motor Company, moved the family several times. Her mother, Martha, struggled with alcoholism.8 They lived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, from 1959 until 1962. As a young child, she was closely attached to her nanny, Ercilla, who helped her develop multiple language skills, a love of local parks and museums, and encouraged her creativity. In an application to study at the American Academy in Rome, Bahnmiller describes the “instinctual exploration” she developed in South America. She wrote:

“My conceptual view of beauty and harmony of place is a recollection of the profile of a diverse geography, a dense image of urban formations. Early residence in Buenos Aires and contact in Rio De Janeiro, Montevideo, and the range of vivid Latin experiences was visually instrumental. Initial education at a Montessori school within a city rich in public parks, theater, architecture, and correspondent mythologies veined with a narrative history, shaped my vision and motivations within my work to date.”9

She often worked odd jobs, mainly in catering and the food service industry. While working for Bonnie Fishman’s Patisserie on Northwestern Highway in the metro area, she badly burned her leg. When asked how it happened, she said, “I tried to iron my uniform, but I was wearing it!”

One time her father got her a job working at the Oakwood Hospital Pharmacy. He bought her a used car to get to work and she was fired after two days. “They EXPECT me to drive to work,” she said, “They EXPECT me to arrive on time. And they EXPECT me to follow orders!” She was further estranged from her family and their support was gone.10

Bahnmiller’s art touched on class, poverty, trauma, war, sexuality, violence, politics, urban living, history, death, Detroit, and literature. Satire is commonly used in her depictions of stagecoaches, as stand-ins for technology and nature overturning the urban world. In her last 10 years, she made variations of enigmatic self-portraits presenting both portrait and mask, abstraction and figure. These too were a kind of satire, on her personal “look” and on feminine tropes, riffing on her hero, Anna Akhmatova, who faced oppression and blight in Stalinist Russia, mirroring her own situation in Detroit.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3Recently, paintings have changed in their expression of a more interior world. Directly linked to this change is the literature of Henry James—a world wherein the “interior” often replicates the construction of human consciousness. The writings of Emerson in conjunction with French Existentialism, Cocteau, and the lineage of not only German philosophy, the Frankfurt school, but the progression from ancient Greek philosophers, is of paramount importance to my work.

The idea of “aufgehoben” from Hegel as explored by Gadamer, is essential—that which negates and surpasses—not only applied to a city such as Detroit, where content has been lost on a massive scale, but also in my search for form. The final construction and process often results form negation.

I am attempting to depict a biography of Nature. The geometric transcription of the history of idea and its relation to the form of everyday life has led to the understanding of how space often expressed through imperceptible change is multi-layered. Concurrent to the study in philosophy is work in architectural theory. Le Corbusier, and the fiction and critical writings of James, Wharton, Flaubert, Cather and Dickinson—the study of negative dialectics.

What I am approaching and expressing in the paintings is the possibility of a spirituality of order. Painting is my most serious life’s work and my commitment to the work is unwavering. Being situated in the Great Lakes region not only provides for a unique study of light, but the backdrop of a city shaped by prehistory and archeological sedimentation of form, enhances study in the direction of the philosophy mentioned above. The stark absence of an “outer” world necessitates the imaging of the interior.

–Artist statement from alumni exhibition brochure, Jean Paul Slusser Gallery, School of Fine Art, University of Michigan, 1992

The artist is a man, himself nature and a part of nature in natural space

–Paul Klee, Ways to Study Nature, 1923

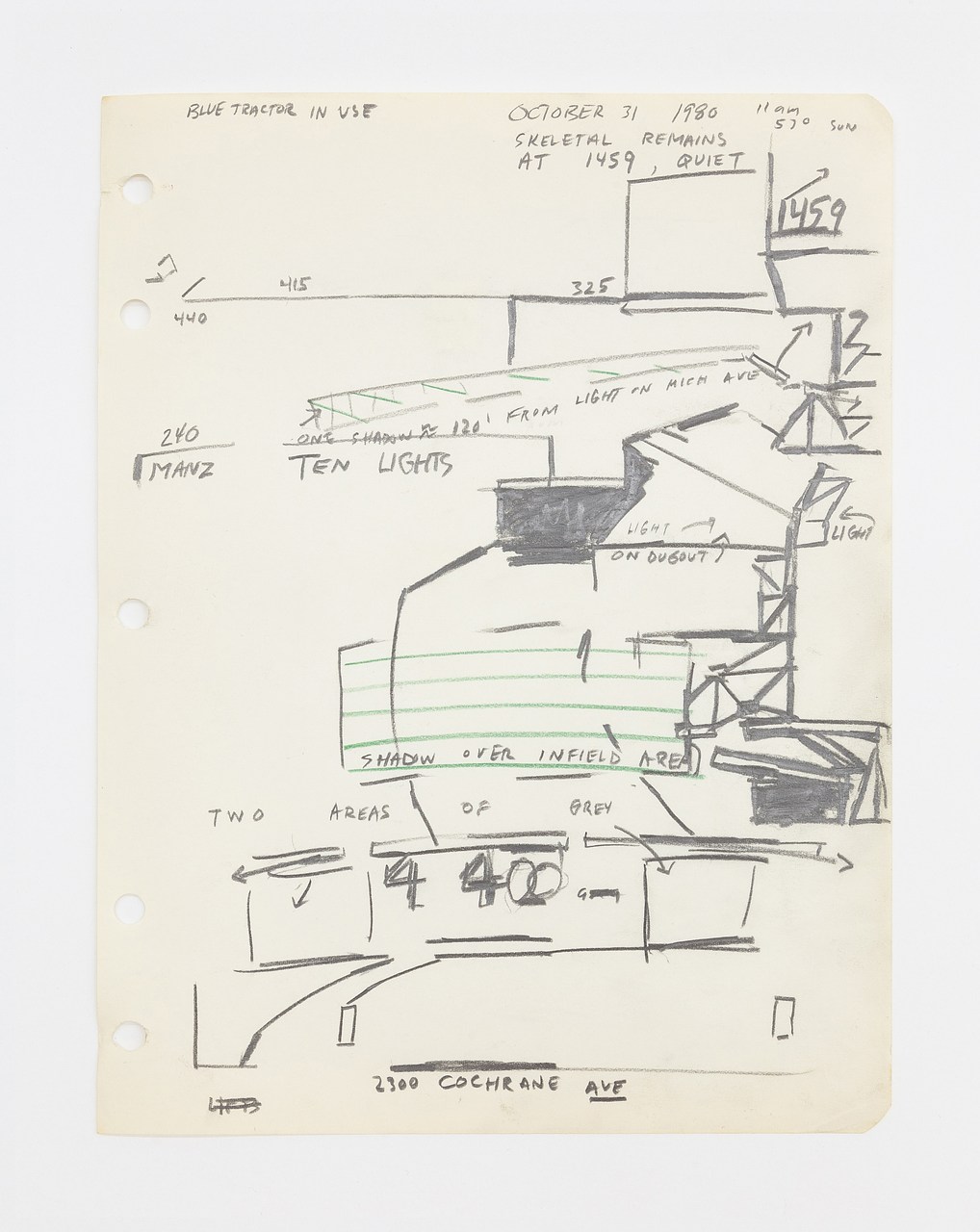

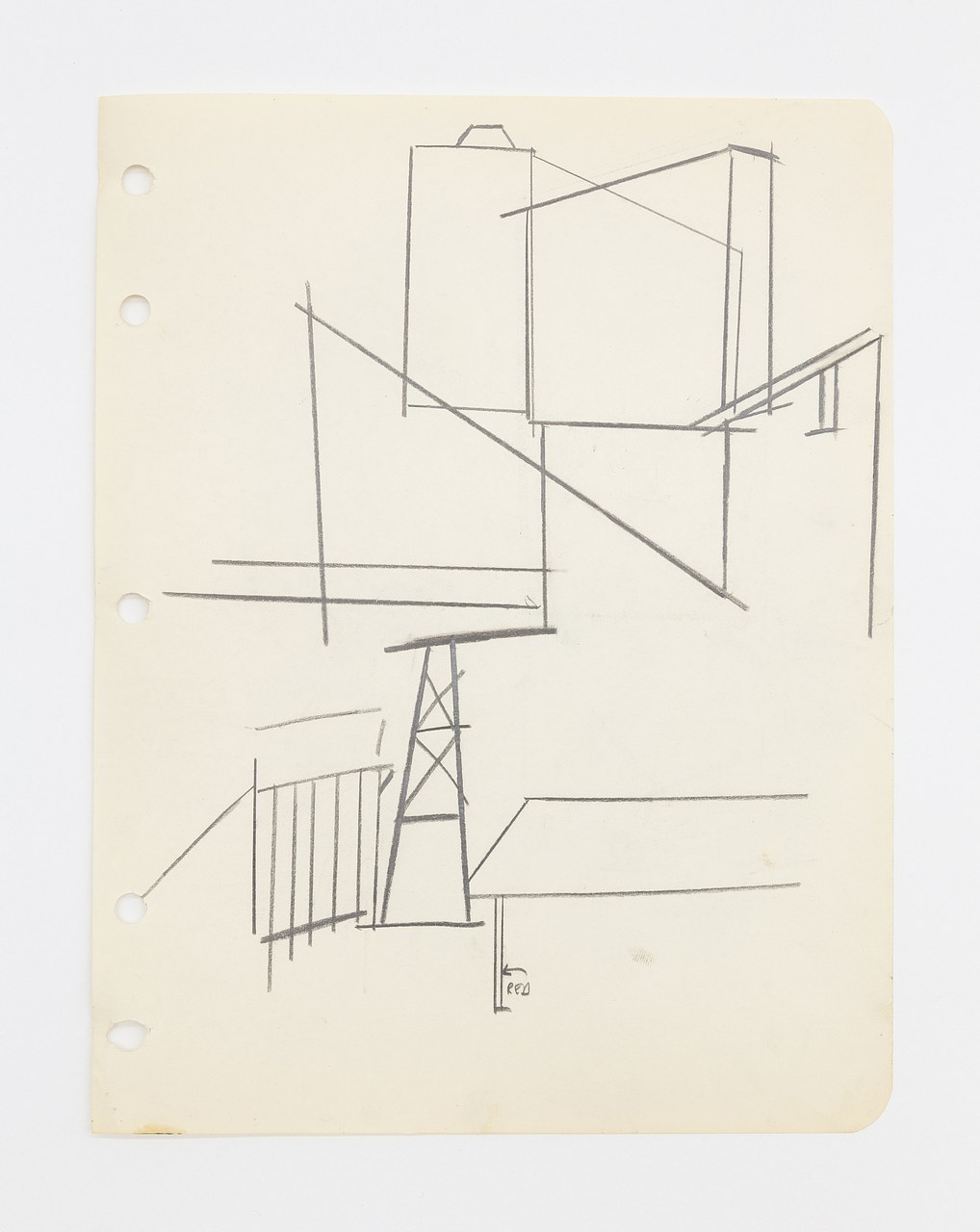

After moving to Detroit in the late 1970s, Bahnmiller began a daily series of drawings that mapped locations around the city using her own symbols. Supplemented with painted blueprints, ephemera, and notebooks, she wrote detailed observations that dealt with the movement of people and transportation. The drawings gave a macro and micro “Proustian” view of the city. This vast collection of research resulted in her first solo show at the metro Detroit Feigenson Gallery in 1980, entitled “Transportation = Transformation = Translation + Land According to Use.”

“While Bahnmiller’s work is about change—actual sites transformed by weather or human use or misuse, and the artist’s transformations through her art,” wrote Dennis Nawrocki, “It is also fundamentally about connecting, locating, placing, documenting, establishing and grounding oneself.”11

A flyer was given away at the opening, characterizing the work: “color Xeroxes, notebooks, drawings and paintings result from investigations of specific areas of land, buildings, roads, and means of transportation in Detroit, beginning at a soccer field in September of 1979, and expanding to include Manz Field, Clark Park, Tiger Stadium, the Rouge Complex, City Airport, the Detroit River and two fields in Canada.” The thorough quality of observation and documentation remained a constant feature in all of Bahnmiller’s art and future exhibitions. Bahnmiller’s detailed notebooks from the exhibition covered weather, time of day, traffic patterns, and the “Theater of Functions” she saw as the constant motion of people in action and the activity of reconstruction happening everywhere. It was an investigative and conceptual project she never really left.

A notebook entry from February 17, 1980:

“What is more real than landscape? One o’clock outside St. Anne’s Church, cold, light is white. Color of blue-grey-green car. What is more real than this landscape? These pictures? The Watchtower. Should I stay in the city and search? Look at the towers, remain local?”

April 14, 1981:

“The life of the river being one strong natural shaping of this area, where is that line reinforced or repeated in the city, or is it?”

Gallerist Susanne Hilberry was an essential part of the Detroit art scene. She helped build a community of artists and brought international art stars to the city. Trained under legendary museum curator Sam Wagstaff, Hilberry brought a keen, adventurous eye and casual elegance to her gallery, first located in a basement suite at 555 Woodward in Birmingham before it relocated to Livernois Avenue in Ferndale. She showed a select group of Detroit artists that included Gordon Newton, Nancy Mitchnick, and Ellen Phalen. Hilberry was also an emotional pillar, confidante, and dealer for Bahnmiller.

“I remember once, Cay was having a really bad time,” recalls Hazel Blake, the former gallery director at Hilberry. “Susanne was trying to get her some help with finding doctors, and to try and get her some better, more consistent care, but I don’t think she had much success.”

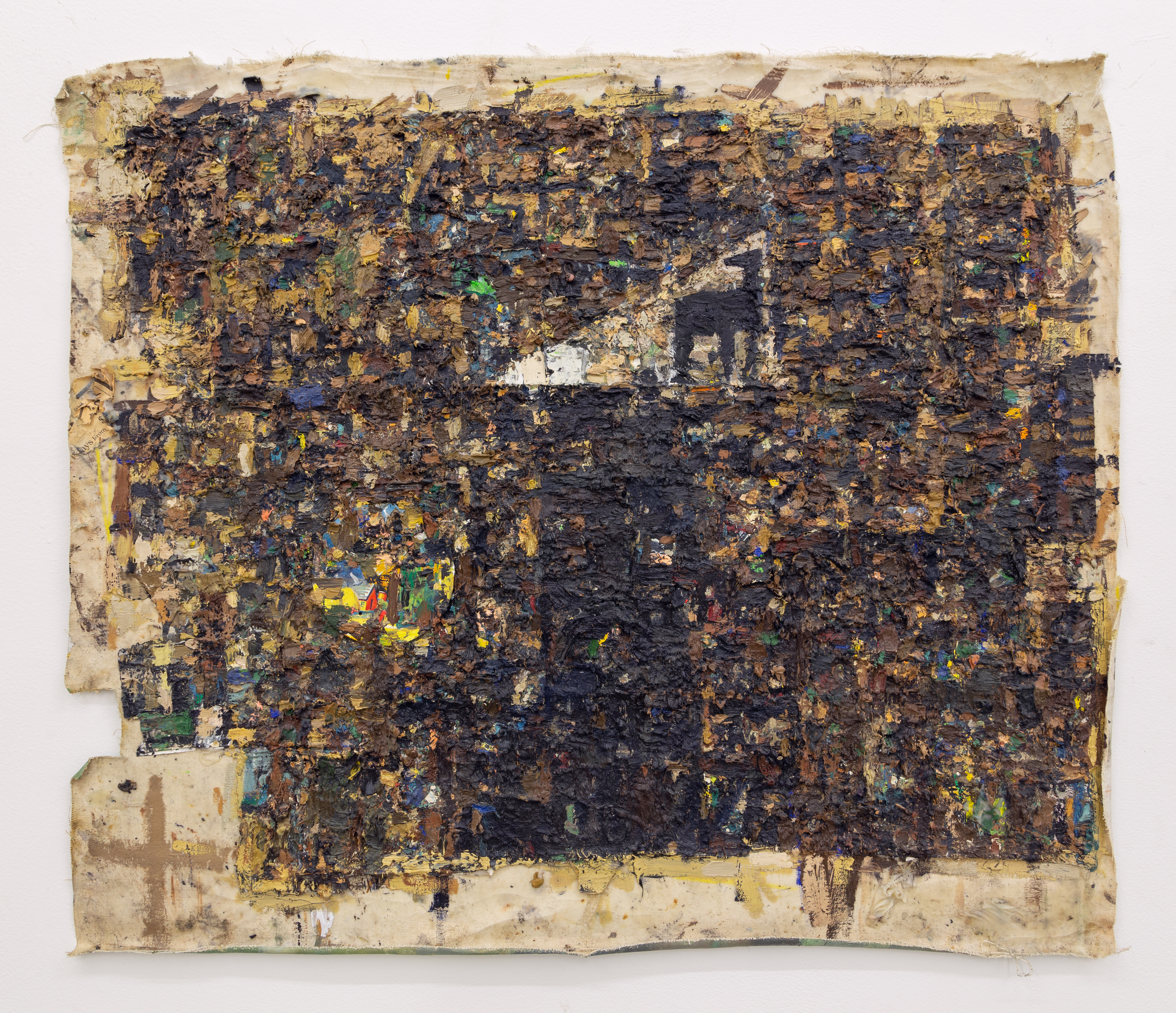

Her last retrospective at the gallery was in 2003. Susanne Hilberry sent a van over to Bahnmiller’s Park Street home and they loaded it with more than 70 works of art. The gallery installed one of the most mysterious and wonderful exhibits seen in the city. No description or photograph of Bahnmiller’s art can ever do them justice. They are objects of an immediacy of the real: sculptural, painful, visceral. Only the naked eye could reveal their interior secrets and thick, tactile layers applied.

Her paintings and assemblages are so dense and packed with subtlety and detail, they are like performance works that require a physical audience. An interview with Bahnmiller in the Detroit Metro Times appeared during the exhibition’s run. “I’ve always been told I’m too sensitive. I find that most of the world isn’t sensitive enough,” Bahnmiller explained in the article. “I’ve had some people say that they find the show troubling. That pleases me. If you’re comfortable today, I’m a bit concerned because there are so many people that are not comfortable.”12

Read next: The Artist Books: A Catalog Project, from Doom and Glory in the Cass Corridor: A Dossier on Cay Bahnmiller by Cary Loren

Special thanks to Daniel Sperry and Alivia Zivich at What Pipeline for access to the artist’s archive, Robert Lebow, George and Chris Tysh, Beth Aviv, Ellen Phillips, and Hazel Blake.

Cary Loren is an artist and member of Destroy All Monsters. He is co-owner of Book Beat, an independent book shop in Oak Park, Michigan.

Lead image, Cay Bahnmiller (presumably in the backyard of her Park Street home in Detroit), date unknown. Courtesy What Pipeline, Detroit.

Fig. 2, Cay Bahnmiller, Country Calico, 1985-89, oil, metal tin on unstretched canvas, 28 x 32 inches. Courtesy What Pipeline, Detroit.

Fig. 3, Cay Bahnmiller, Untitled (head), December 2006, oil, latex on canvas, 13.5 x 10.25 x 1.75 inches, Courtesy What Pipeline, Detroit.

Fig. 4, Cay Bahnmiller, Untitled (Transportation = Transformation = Translation + Land According to Use series), 1980, graphite, color pencil on paper, 10.375 x 8 inches. Courtesy What Pipeline, Detroit.

Fig. 5, Cay Bahnmiller, Untitled (Transportation = Transformation = Translation + Land According to Use series), 1980, graphite on paper, 10.375 x 8 inches. Courtesy What Pipeline, Detroit.

Fig. 6, Cay Bahnmiller, For Those Who Are Too Wounded To Speak / Kofi Anna, 2003, oil, latex, Sharpie, tape, plastic, fabric, on metal sandwich board sign, 30 x 30 x 14 inches. Courtesy Susanne Hilberry Gallery and What Pipeline, Detroit.

Endnotes

1. Cay Bahnmiller, undated signed letter, Cay Bahnmiller archive, What Pipeline, Detroit.

2. Cay Bahnmiller, Guggenheim grant application, 1994, Cay Bahnmiller archive, What Pipeline, Detroit.

3. George Tysh, signed letter of recommendation, May 13, 1987, Cay Bahnmiller archive, What Pipeline, Detroit: “She taught courses entitled “Dickinson and Mallarmé” and “Grammatical Space.” The former involved a brilliant comparison of American and French poetic contexts as well as a discussion of negation and contradiction, which has deep resonances in Cay’s own work as a painter. The latter dealt with writings by poet Charles Bernstein, architects Aldo Rossi and Louis Kahn, and critic-theoreticians Adorno, Blanchot, Derrida, Husserl, Kounellis and Wittgenstein; and again Cay was able to draw on her concrete experiences as a visual artist by way of making these texts more accessible to her students. For if any of the above-mentioned material seems to imply great difficulty or cold abstraction to the casual observer, Cay’s warmth and sensitivity to students, her personal, artistic commitment to the ideas under discussion, and her ability to connect subtle concepts to everyday life make her an uncommonly valuable teacher. Though I am a poet, teacher, and arts administrator and not an art critic or art historian, I feel that I can safely praise Cay’s work as a painter. Hers is one of the most rigorous, extraordinary, investigative visions that I’ve yet encountered. Each of her works is intensely physical, yet embodies a rich dialectic of concepts and perceptions of the urban environment.”

4. Charles A. Blessing, letter of recommendation, 1984, to Gentlemen of the Jury, Rome Prize Fellowships 1985/86, The American Academy of Rome, New York, N.Y., Cay Bahnmiller archive, What Pipeline, Detroit: “Cay Bahnmiller has progressed and daily progresses farther in the world of the intellect and of verbal-visual relationships and patterns than any young painter I have ever known. She is at one and the same time a self-programmed researcher, field investigator, tireless student of the greatest masters and thinkers in literature, phenomenology, semantics, philosophy of art—she is in the most direct way I can express it—intellectual and painter in one. Cay Bahnmiller, is in its fuller meaning and significance, a new “autobiography of an idea,” Cay’s own idea of what she is qualified to do as one who is richly talented and equally richly equipped and motivated by her scholarly dedication, her intellectual capacity and her great talent as one destined to seek and achieve greatness in her lifetime. Her vision is unbounded, her determination no less.”

5. Mary Jane Jacob, signed letter, Sept. 22, 1980, Cay Bahnmiller archive, What Pipeline, Detroit: “In the short time I have known this artist I have been able to see a wide range of works from a series of projects. So active and intense is her involvement right now that one is able to observe almost daily leaps in her art. Certainly this is a crucial and exciting period in her development. In these works, Bahnmiller shows her connection to recent Detroit work as well as her uniqueness and independence… This tension created by the combination of expressive and intellectualized approaches contributes to the strength of Bahnmiller’s work. Becoming familiar with Bahnmiller’s work and feeling it was among the most interesting work being done right now in Detroit I have introduced it to others so that it might receive the exposure it deserves.”

6. Cay Bahnmiller, letter to N___ in the collection of Robert Lebow, Oct. 7, 1996

7. Cay Bahnmiller, letter to Ellen Phillips, August 2005

8. Author’s conversation with Robert Lebow, Sept. 2, 2021

9. Cay Bahnmiller, application letter to the 1985 Jury, Biennial Competition in Painting and Sculpture, Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation, New York, Sept. 30, 1985

10. Author’s conversation with Robert Lebow, Sept. 2, 2021

11. Dennis Nawrocki, “Cay Bahnmiller,” New Art Examiner, February 1981

12. Melissa Giannini, “Out from the Dark,” Detroit Metro Times, Oct. 29, 2003