The Xerox Myth

Copy Machine Creation in Destroy All Monsters

In advance of the retrospective exhibition “Mythic Chaos: 50 Years of Destroy All Monsters” at Cranbrook Art Museum [November 2, 2025 through March 1, 2026], artist and founding DAM member Cary Loren hones in on a particular art form that shaped their collective cosmology.

Long before scanners, Photoshop, and home printers, the mammoth copiers tucked away in campus shops became our darkroom, printing lab, and myth-making device. For Destroy All Monsters in the early 1970s, Xerox wasn’t only about reproduction—it was transformation.

Xerox art thrived on imperfection and immediacy. Xeroxing gave us speed, interconnection, saturated images, and a Dadaist ethos. Each copy could be reworked, mutilated, or discarded. Its cheapness was its strength—forming the aesthetic of punk zines and assemblage art, and a process that pushed limits. Xerox tones ranged between high grain to high contrast. Areas of shiny solid black carbon were possible depending on the machine, and gave the surface texture and dimension, while enlarged grain and fuzzy edges made the analogue distortions feel softer, more mysterious and alive than today’s crisp digital copies.

Jim Shaw’s Etched Shadows

While working at the Michigan Union art supply store in Ann Arbor, Jim Shaw, then a student at University of Michigan, had access to a large commercial machine. The toner was somehow souped up to release extra carbon and produced extraordinary deep inky blacks. “They looked like fine etchings,” recalls Shaw.

He collected all weird forms of visual illustration, including early MAD Magazines, pulp paperbacks, Weird Tales, Mars Attack trading cards, and atomic fifties fabric designs. His collections became source material, mixing camp 1940s Life Magazine adverts with 1960s comic books, human anatomy charts, dinosaur paintings, and lurid fragments from S&M magazines—collaging these disparate elements into uncanny parodies of American life.

Shaw gained plenty of graphic design experience creating fliers for Ann Arbor’s Cinema II. He made them daily, grinding them out for upcoming screenings on campus. Each flyer featured a single image he created to attract an audience. His Xerox art promoting Destroy All Monsters used similar methods, like hand lettering or rubbed on ben-day dots, but the images were less constrained and more surrealist, juxtaposing giant fish, sports pennants and other oddities into a sci-fi stew. Shaw had a Destroy All Monsters movie press kit he used alongside his clipart, inserting the film’s logos and promotional elements onto the Xerox.

Large wall displays of Shaw’s copy art were shown at the Michigan Union gallery. These were monumental exhibitions using serial images and variations on themes; a deconstructed jigsaw puzzle, a mass of dark jungle fabrics, and a woven collage made of color Xeroxed collages. By sliding images under the moving lightbar, Shaw introduced blur and motion into the frame, turning the mechanical process into performance. His Xeroxes mocked postwar consumer innocence while flirting with Surrealism’s darker dreams—irrational thought, violence, and desire unbound.

Monsters and Memory

My own Xeroxes combined the mythos of Hollywood film and pop culture, with private photographs and those from family albums. By laying in and splicing photographs of monsters, movie stars, and political icons with personal and family snapshots, I created unstable composites that blurred the boundaries between myth and autobiography. Figures like the Wolfman, Count Dracula, Boris Karloff, President Kennedy, and cheap pin-ups fused with portraits of Niagara, friends and family, forming a new hybrid reality—one both familiar and estranged, haunted by the ghostly aura of the photocopier itself.

I often photographed off a TV screen or inside theaters, taking frames from Marilyn Monroe films, Japanese kaiju and horror movies, Warhol films, and Felix the Cat cartoons. I collected old scrapbooks and used turn-of-the-century illustrations, laying in Victorian chromolithographs of cats, angels, Valentines and flowers. Cutouts from paint-by-number kits, wrapping paper, and optical art patterns became the background of a new world. Crinkled cellophane fractured by the copy machine’s light bar added a surface textured like broken glass. Light manipulation, hand-coloring, and backgrounds were the connective tissue of collages, fusing the chaos into something more cohesive and strangely beautiful.

If Shaw’s collages parodied the middle class, mine sought to mythologize the detritus—to turn the ruins of pop culture and family history into personal myth.

Niagara’s Glamorous Interventions

Many Xeroxes were hand-colored by Niagara, who transformed their surfaces into glowing, tactile relics. Her pigments of hot pink, icy blue, metallic green floated over the toner like a second skin. Images from our photo shoots and clippings melded into a coloring book fantasy. She reintroduced the hand into the mechanical process, adding theatrical and feminine energy. The grotesque became glamorous, each reproduction an object of enchantment. We sometimes hand-colored and spray-painted our work in group sessions with friends. Coloring gave the copies a psychedelic, trashy, and vibrant surface, adding whimsy to the aesthetic, an artificial beauty decorating the decay.

Mike Kelley’s Anti-Xerox

Mike Kelley made only a few Xerox pieces. One was a distorted self-portrait, face pressed to the glass, gripping a toy rubber shark. A punk act of self-defacement, an anti-image mocking both art and technology. For Kelley, Xerox wasn’t fantasy or montage, it was a confrontation—an imprint of body and marked absurdity.

Collective Alchemy

We each approached the machine differently but together we made it a ritual of transformation and chance encounter, sampling artifacts on the platen glass. Shaw’s sociological Surrealism, Niagara’s glam interventions, Kelley’s defiant humor, and my own monster mythologies converged on the page. We passed around and shared piles of our art in a democratic manner. Ideas developed as we worked at the machine.

The first color Xerox appeared in 1973. The machines weren’t easy to access but when we could it cracked open new techniques, with multiple color bar scans allowing us to superimpose imagery and saturate color. Shaw had access to a color Xerox machine at Cranbrook in 1975, one of the first installed. A couple years later dollar-per-page color machines were in retail card shops in Los Angeles and Royal Oak, Michigan.

There were relatively few venues to showcase Xerox art in the 1970s outside of Lightworks (a magazine about experimental art published in Ann Arbor), the Michigan Union gallery, and through the mail art circuit, where Xerox art and staple-bound zines freely circulated. This energetic era of Xerography led directly into making Destroy All Monsters magazine. While several issues included Xeroxed covers and inserts, a faster cheaper way of reproduction was needed, which led me to learn the basics of offset lithography and using an industrial copy machine camera.

Our Xeroxes survive as relics of that restless moment when art, music, and life converged. The rawness and spontaneity of Xerox art was prophetic, anticipating the remix culture that defines our time. Xeroxing was an instrument that turned memory, noise, and cultural debris into something spontaneous, new, and our own.

The Ghost in the Machine

New communication devices and technology are tools and metaphors following a parallel history of spiritual change, constantly shifting older beliefs. Scientist Michael Farady (1791-1867), who invented the first electric motor and showed the connection between light and electromagnetic fields, was devoutly religious, and felt he was directed by God. “The book of nature which we have to read is written by the finger of God,” Farady said. His experiments in electrostatics became a key component in the later work of Chester Floyd Carlson (1906-1968), inventor of the copy machine. Carlson used electrostatics to fix carbon particles, a process governing the laser printer still today.

On October 22, 1938, Carlson discovered electromagnetic photography—later renamed Xerox after the Greek words xeros for dry and graphein for writing. By selling his patents to the Halloid (Xerox) corporation in 1949, Carlson earned a royalty of one-seventeenth of a penny on each copy and by 1965 had accumulated more than $150 million in patent licenses. He and his wife held group Zen meditation sessions at home and spent their final years giving away most of their wealth to the NAACP, the Civil Rights movement, and to spiritual and parapsychology groups. Carlson died of a heart attack in 1968, at a public theater in New York, while watching the British crime drama He Who Rides a Tiger.

Journalist Tom Shroder documents hundreds of reincarnation cases from India and around the world in his 1999 book, Old Souls: Compelling Evidence from Children Who Remember Past Lives. The research was gathered over a 40-year period by Dr. Ian Stevenson at the University of Virginia, whose life work was funded by none other than Carlson. The inventor immersed himself in Stevenson’s research and endowed the University to continue the work beyond his own death.

Analogue Xerox machines from the 1970s no longer work. Their parts are irreplaceable and can’t be repaired, which means that copies from that era and years prior are one-of-a-kind archival prints of fused carbon. They don’t fade, either, unless the paper or backing happen to be acidic.

In 2023, the Brooklyn Museum mounted the first major exhibition of copy machine art in North America: “Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines,” curated by Branden W. Joseph and Drew Sawyer. The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue contained more than 800 works by 100 zine-makers, including early art by Destroy All Monsters.

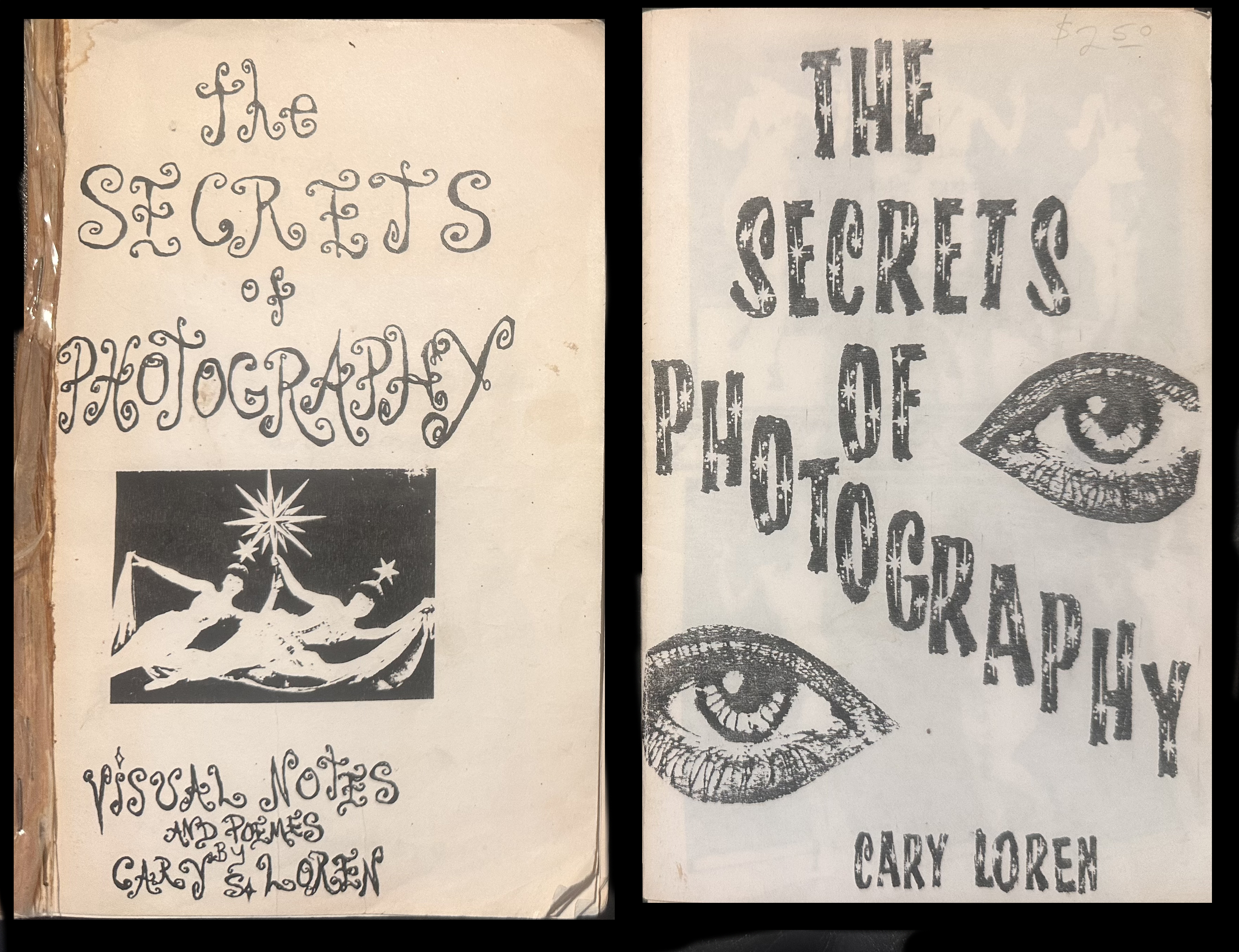

In 1980, I self-published two editions of The Secrets of Photography, a 78-page Xeroxed book of poetry, aphorisms, illustrations, and quotations on photography and Xerography. The second edition of my artist book was included in Brooklyn Museum’s exhibition. It joined together the foundation and invention of Xerox with the study of theosophy, mythology, and the practice of photocollage. Here are excerpts from both editions:

Mythos & Technique: the camera is a poor invention / to think how we once/ sent imagery/ thru our tele-photo mind

images consume reality

the camera is a tool / to up-root our dreams

Xerographis/ The desire to copy images is to believe in no limitations / Xeroxing leaves a trace of carbon on the memory/

Eleusis…mystical theater/ for 2000 years the mystery was taught every year (except one) at the height of Greece/ before the appearance of Christ/ the mimetic journey/ to claim back from death/ the daughter of grain mother Demeter/ the canvas of carbon found in all living matter/

Cary Loren is an artist and member of Destroy All Monsters. He is co-owner of Book Beat, an independent book shop in Oak Park, Michigan.

Lead images: Untitled, Cary Loren, Xerox, 8.5 x14 inches, c. 1975-1976.

Fig. 1, Untitled, Jim Shaw, Xerox, 8.5 x 14 inches, 1975.

Fig. 2, Untitled, Jim Shaw, Color Xerox, 8.5 x 11 inches, 1976.

Fig. 3, Untitled, Jim Shaw, Color Xerox, 8.5 x 11 inches, 1976.

Fig. 4, Untitled, Jim Shaw, Color Xerox, 8.5 x 11 inches, 1976.

Fig. 5, Untitled, Cary Loren, hand-colored by Niagara, Xerox, 8.5 x 14 inches, 1975.

Fig. 6, Untitled, Cary Loren, Xerox, 8.5 x 14 inches, 1975.

Fig. 7, Untitled, Cary Loren, Xerox, 8.5 x 14 inches, 1975.

Fig. 8, Whisper, Cary Loren, hand-colored by Niagara, Xerox, 8.5 x 14 inches, c. 1975-1976.

Fig. 9, Untitled self-portrait, Mike Kelley, Xerox, 1975.

Fig. 10, Untitled, Cary Loren, Color Xerox, 8.5 x 11 inches, 1978.

Fig. 11, Untitled, Cary Loren, Color Xerox, 8.5 x 11 inches, 1978.

Fig. 12, Untitled [cover of Destroy All Monsters Magazine], Cary Loren, color Xerox, 8.5 x 11 inches, 1978.

Fig. 13, Two editions of The Secrets of Photography, Cary Loren, 78-page mixed media Xerox book, 1980.

Also by this author:

Make Room for Dada: A Dossier on the Ridgeway Collective