What is in a Name

The many brilliant Black women you evoke when you say Imani

By Imani Mixon

By Imani Mixon

A first name grants you your personhood, some humanity to specify exactly where you fall in your legacy. We live in a patriarchal society where babies are given their father’s last name, where we exclusively trace our roots and measure their value by the fickle weight of paternity. My last name does not necessarily tie me to one place nor deeply root me within a family tree. It creates a distance from both my mother and my sister even though they know me best.

It is apparently a mouthful when read from a roll call. Its phonetic spelling—the I in Imani pronounced exactly as the I in Ian—is supposedly too complicated. My first and last name together, I have been told, are just cool enough to sound both Black and professional. I enjoy their symmetry: Five simple letters each, enough vowels to give your mouth a break between pronunciations. Unfortunately, my last name does not sufficiently answer the same questions that my first name does. I am Imani, I was born and raised in Detroit, and my first name means faith in Kiswahili. It is the seventh principle of Kwanzaa, the holiday Dr. Maulana Karenga invented in 1966 to celebrate Black collective heritage and eventual liberation. Kwanzaa starts the day after Christmas and a different principle is celebrated each day. This means that on January 1st, as the rest of us are celebrating a new year, some of us are celebrating “Imani.” To call me, is to call on belief, hope, and endurance. In 2016, Detroit called me back from Chicago. What is most remarkable and memorable about returning home is not who I found in my first couple years back home, but who found me and what they also answer to.

The First Encounter

Upon arriving back home to Detroit, I returned to a city that had changed immensely since I left. I needed to build a new community and find a new inner circle. I started frequenting places that I either hadn’t heard of before or places that didn’t even exist when I left for Chicago in 2010. After unceremoniously quitting the marketing job I had moved back home for, I started working as a communications assistant at Allied Media Projects. I met radical, generous, cool as hell folks who were carrying work and life in a way that I had never seen before. I attended my first Allied Media Conference, their 19th annual convening, in June 2017.

I particularly remember one workshop, “Black Touch: A Somatic Healing Space,” that I was both hesitant and excited to attend. It was a Black-only space led by Angela Davis Johnson and nyx zierhut, designed to teach us how to get in touch with ourselves and each other. The energy of the room was warm, welcoming, vulnerable, and slightly charged with uncertainty. Just how much touching would we be doing? How can you lovingly set boundaries in a room full of strangers when the sole purpose is to connect with each other?

We completed a series of exercises; one involved mirroring a partner you chose at random, with a nod or eye contact, then finding a space with enough room for you both to mimic one another’s actions, sometimes leaning in or resting upon the other. We also participated in a larger group exercise where we were instructed to stand in a circle, each of us facing the back of the person in front of us. We were asked to slowly lean back, trusting the individual behind us to offer enough support to remain upright.

I wasn’t thrilled about the exercise; trusting someone I don’t know with the weight of my body is not my idea of fun, or even connection. As I eased into the exercise, I realized that the person behind me was holding me up with a soft power and pushing me forward. We held this stance for a few minutes, the room silent and attentive. The exercise ended and everyone slowly, carefully, returned to an upright position. We rose from that momentary daze and began introducing ourselves. The exercise opened me up in a way I wasn’t expecting. We were encouraged to speak after spending an hour in relative silence. I turned around and introduced myself to the stranger who had been holding me, a nice-looking young woman, smiling, with curly hair and glasses.

“Hi, I’m Imani,” she said.

“Oh my gosh, me too. Hey girl!”

I call that Imani, 26-year-old Imani Spence of Baltimore, Maryland, who is a fellow Scorpio, current master’s student of library science and an abortion funder.

“So much of being Black is looking over your shoulder and so much of being a Black woman is trying to be a certain way,” says Imani Spence.

Imani has family in Detroit. She was visiting the city and living with her grandparents when we met at the conference. We would run into each other again in a Black and Brown yoga class at Hamtramck’s Iyengar Yoga, then at an Ida B. Wells investigative journalism training in TechTown, the kind of event where everyone wears nametags. Her friends told her there was another Imani attending. Of course we had already met by then, but we shared the same sentiment—it’s comforting to know there’s another Imani in the room.

The Second Encounter

In mid-September of 2017, my friend Alyssa, who I most frequently ran into out on the town at this club or that bar or that one party, asked me to come out to Marble Bar to model a few clothes for her friend Dessislava Terzieva’s label, Paid Actor. I was given a chunky black blazer with shoulder pads and a deep-V lapel that cut down to around my belly button. We each put on heels and wobbled upstairs for a few photos. The bar was beginning to fill with chatter and music so we went upstairs and began to dance in our new looks, someone else’s clothes.

One of the other models was also named Imani. In between outfit changes and the shoot we tried to figure out how we’d never met, since she was close with the friend of mine who’d invited me that night. She was also from Detroit and we’re around the same age but for some reason our social circles hadn’t overlapped until that night. In the few hours we spent together, I learned that she practices yoga and was considering a move to Miami.

We were dancing and posing for pictures in the upstairs balcony when a sweet, aromatic smoke rose. At first I thought it was a joint.

“Have you been blessed?” she asked me.

I fumbled for an answer; the music, the smoke, the heels made it hard for me to lock into the moment.

“I think so,” I replied.

“No you haven’t,” she said, and whisked a bundle of sage over and around me, pushing the air with her hands, inhaling and exhaling audibly. She blessed the rest of the modeling crew. A white dude who was close to us, maybe waiting in line for the bathroom, asked, “can you do me too?” And she did. She blessed us all.

I call this Imani, Imani Etay, a 30-year-old yoga teacher and Scorpio moon who is from Detroit and lives in Miami.

“I'm thankful to have grown up and grown into such a unique and powerful name,” says Imani Etay. “Names really do mean a lot. It’s not just something that should sound cute. It should mean something because it can really affect the child. My name has been a part of making me who I am because it’s so different.”

Imani Etay grew up on the near East Side in the Brewster-Douglass Housing Projects, then the Calumet Townhomes in what’s now called Midtown but is still referred to as Cass Corridor by legacy Detroiters. I grew up on the East Side too, first near Mack and Moross, then in the Morningside neighborhood, and then the Jefferson Chalmers area. I’ve been living in Midtown for the last four years, since I moved back. Imani and I had likely been orbiting each other our whole lives but never met.

The Popularity and Distinction of Imani

One website ranked Imani as the 550th most popular name in the United States in 1992, the year I was born. By the time I was four my name had moved up one notch in the ranks, according to the US Census Bureau. Coincidentally, if you rap The Notorious B.I.G’s 1995 hit “Get Money” fast enough, it sounds like Get ’Mani—our nickname—and the song has served as a theme song for Imanis everywhere since.

We are our own community. There’s a certain noise we cut through when we’re together, more than if we shared a name like John or Sarah. The name Imani grounds our state of mind and being. It likely means we had Afrocentric parents who wanted to compel us to stand out. Imani Spence’s dad had a “Black baby names” book. Imani Etay’s mother experienced a few complications with her pregnancy and she was born premature.

“She named me faith because she knew that I would be okay,” says Imani Etay. Her first and last name together translate as “faith through adversity.”

My mom was teaching African-American history to high schoolers when she was pregnant with me. Even before that, she was working at a UPS store in East Lansing and didn’t feel comfortable using her given name to answer calls, so she went by Imani instead and liked the sound of it. Each of us, Imani Spence, Imani Etay, and I, also have siblings with singular names like Kamari, Kiserian, Niara, Khari, Idrissa, and Akil. I named my little sister after another Kwanzaa principle, Nia, which means “purpose.”

“It's like a cohort,” Imani Spence explains. “The ’90s happened and people got really woke ... Everybody was named Imani. I love that I just feel very much like we are all part of a greater movement.”

Over time, I have become an expert of all things Imani-related, especially when it comes to celebs who have chosen our name, in all its iterations: Jasmine Guy’s daughter Imani, Lil Scrappy’s daughter Emani, Talib Kweli’s son Amani. SZA’s middle name is Imani too. There’s my aesthetician Imani who does my brows, the chef Imani who I pick shrimp curry ramen up from once in a while, and the younger Imani, who my mom’s sorority sister named after me. There’s the badass Imani who sometimes has pink hair; she’s from Detroit and is attending Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism, my alma mater. We are everywhere, and yet, we are often the first Imani that anyone who’s not Black has ever met. My small and loving tribe fortifies my existence, strengthening my sense of self. I embody my name as if it’s a mantra.

“Every Imani I’ve met has been dope. I’ve never met a weak ass Imani,” says Imani Etay.

The encounters I had with Imani Spence and Imani Etay in the first two years I moved back home aren’t just synchronicity. This feels divine. It has made Detroit more sacred, blessing my return with warmth and intention. Imani is a place where Black girls gather, hold each other, sage rising. Detroit is a home for faith

Imani Mixon is a writer, producer and long-form storyteller born and raised in Detroit. Her multimedia work centers on the experiences of Black women and independent artists. Read “Super Natural” by Imani Mixon in Three Fold issue no. three.

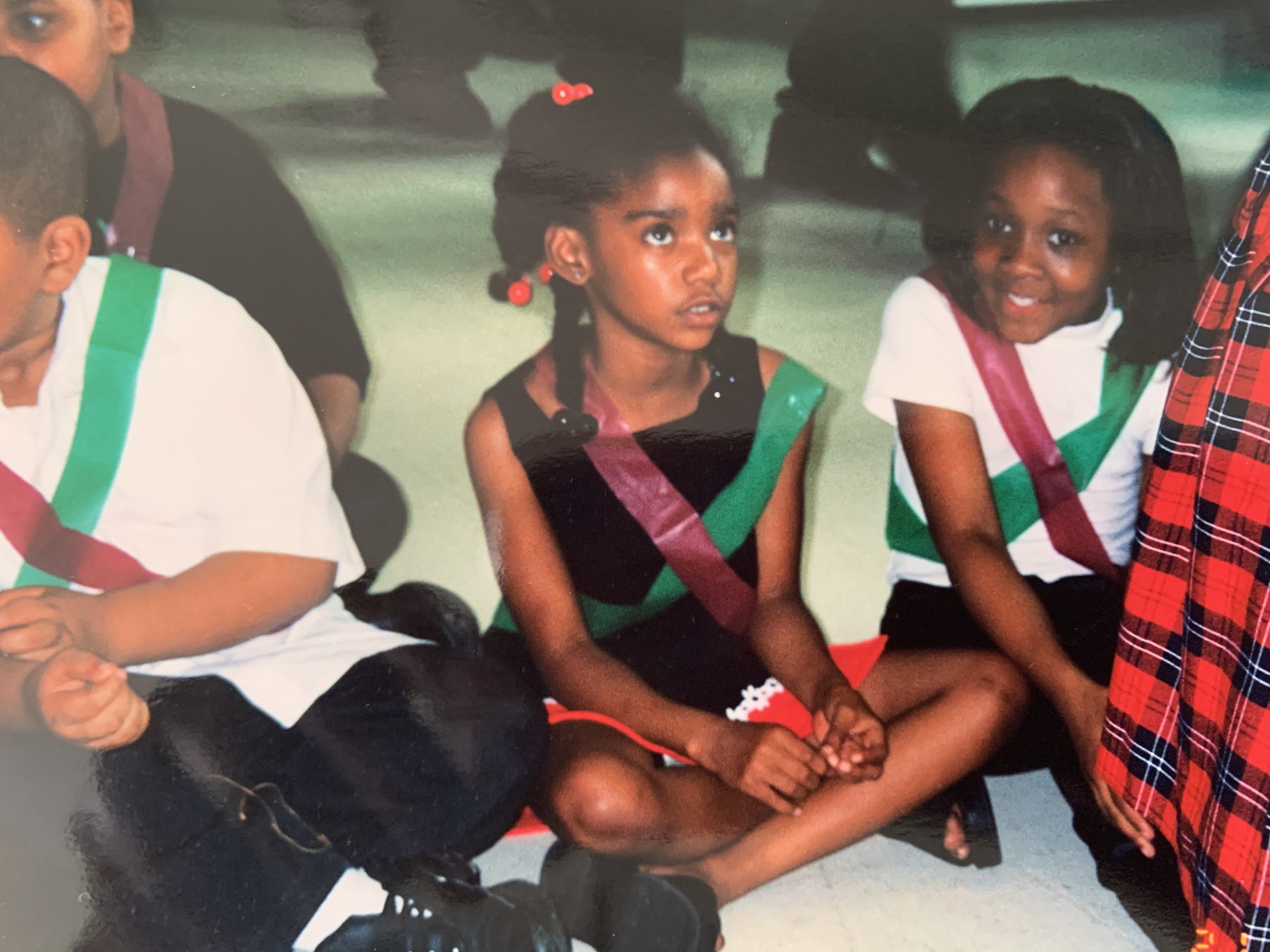

Imani Mixon | photo by Christian Najjar

Read next: Art, Ritual & Theory in Mandenka Historiography by Nubia Kai

Read next: Art, Ritual & Theory in Mandenka Historiography by Nubia Kai