This is What Genre Can Do for You

By Molly Zuckerman-Hartung

Origin Story

The project began with painting everything in the studio with black and white oil paint. Or just white. Including all the half-squeezed-out paint tubes lying on the floor. Fastidious excess. Decadent austerity. Or it began with gum stuck on the shoe. Who's shoe? But that is the violent part made sticky. The heat of the Chicago summer sidewalk, sometimes hot enough to fry an egg on it. The sad and sometimes violent Chicago south side sidewalks passing vacant lots and chain link fences. Flat. Flat means that American A as in hat and bat and whack. Flat also means sleepy. Exhausted but maybe in a sweet way.

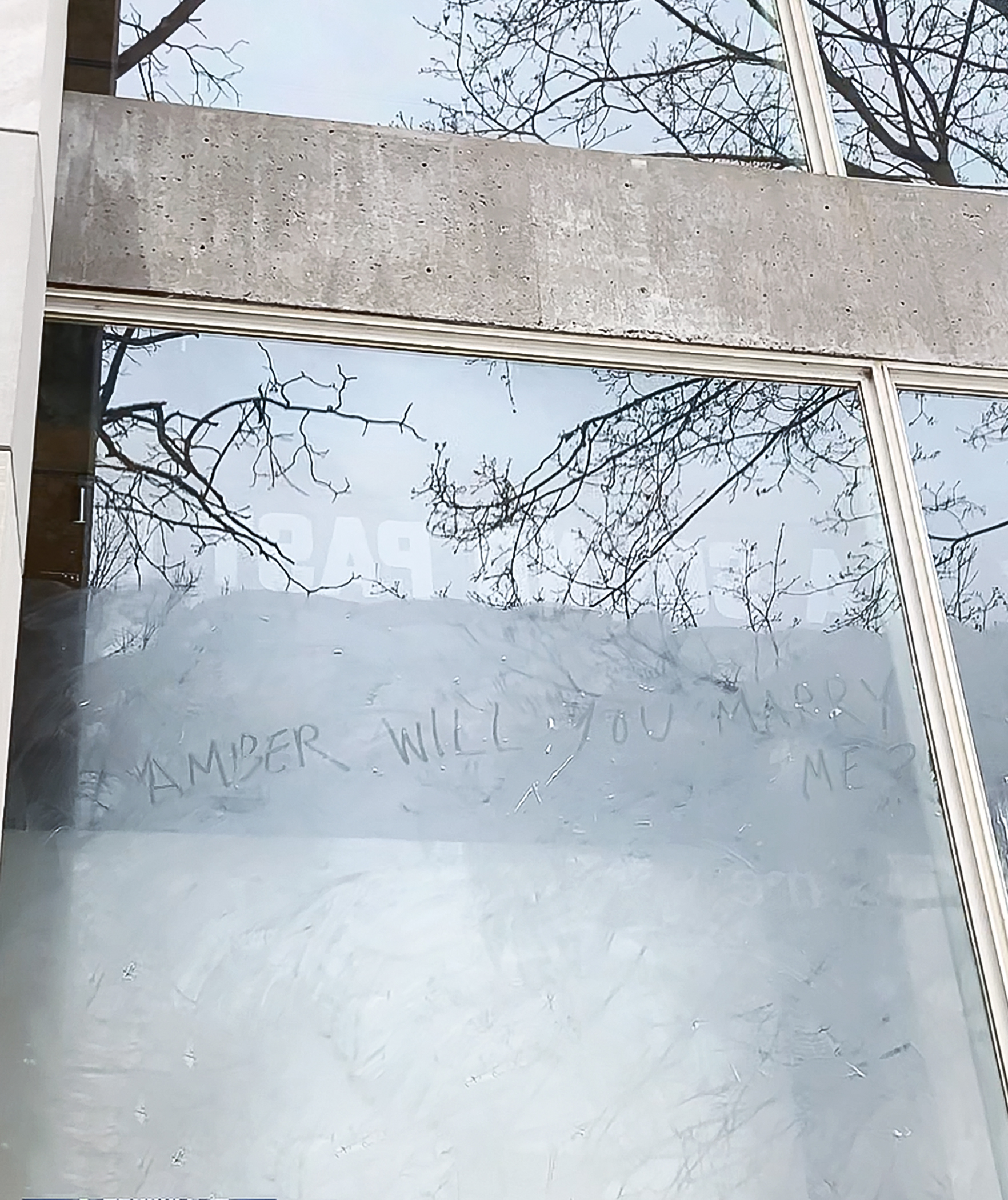

Fig. 1

Fig. 1The stepping in the sticky gum on the hot street is also just a step. The step. The first step that puts you right in the middle of everything, reaching out to everyone and unable to look.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2No, maybe it began with a walk to the grocery/convenience/corner store down the block and a purchase of white roses in plastic wrap with a price tag $8.99 or $12.99 I’m just guessing. Cheap white roses with a plastic packet tucked into the plastic stickered wrapping. A plastic packet meant to be shook into the vase of water these roses won’t see. To extend the bloom of the roses. The rose here is like a can of Campbell’s soup. Infinitely repeatable, banal, and pretty. At the grocery/convenience/corner store the roses are always in bud. Budding young things. Forever young. I’ve never seen them bloom in the grocery/convenience/corner store and I’ve never taken them home to find out what happens.

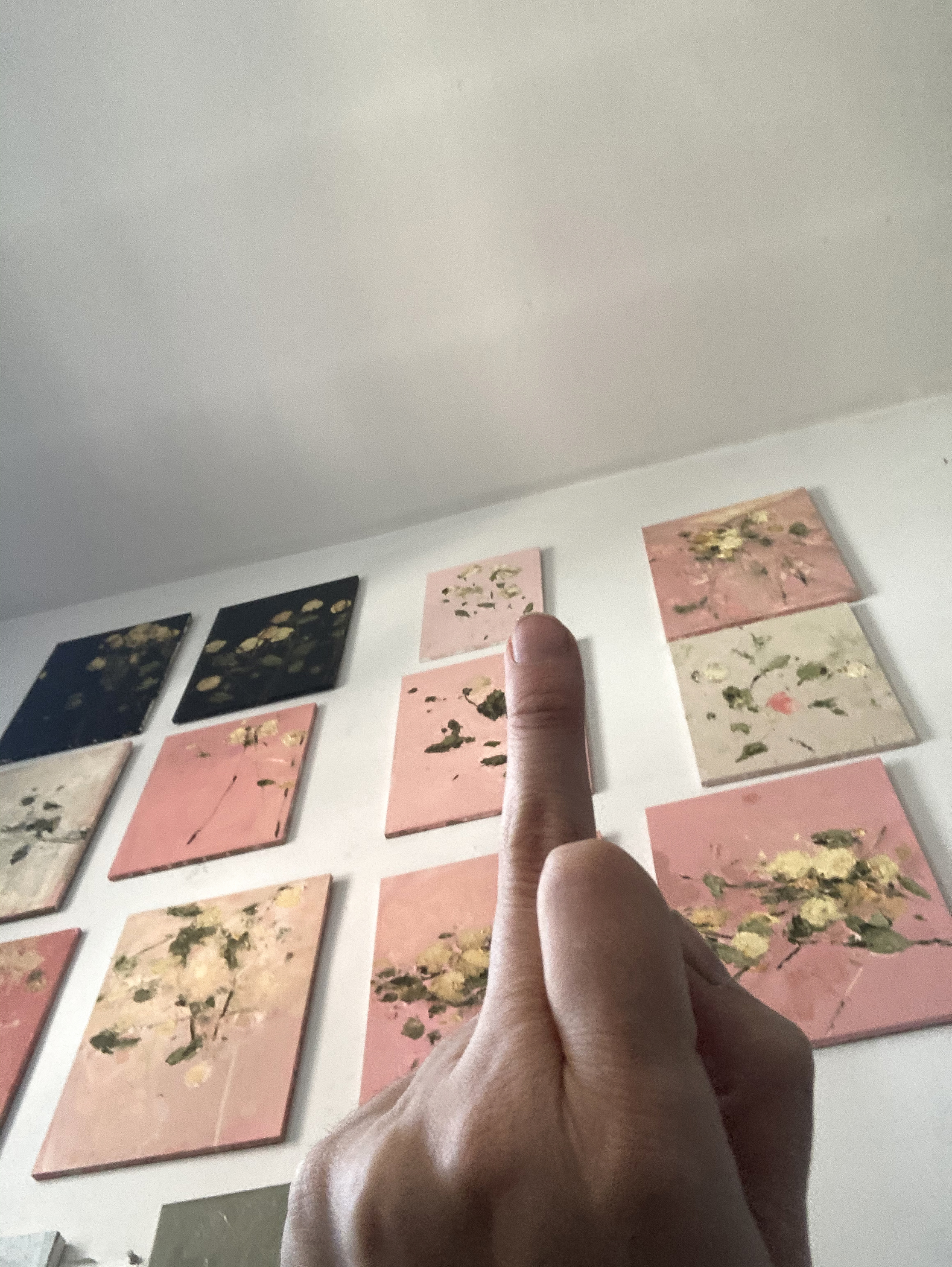

Fig. 3

Fig. 3DeGiulio has. Taken them home. For almost ten years now (if I had to guess) Dana DeGiulio has been buying cheap (it’s important that they are cheap I believe. Important to DeGiulio and so it’s important to me) white roses and taking them home to see what happens. You’d think she’d have some idea by now. Some idea what happens, I mean. I don’t mean to be sniffy, and it might be my circuitous way of admiring, because me, I like the idea of the thing sometimes, or often, more than the thing. But not Dana. I guess that’s why she built a conceptual project. So she could get the idea out of the way quick and get on to the meat of the thing. The super-sad monumental collapsing gasping grand pianissimo stench of the thing that most of us living don’t catch a whiff of until we’re too old to get anyone to listen. That’s the meat DeGiulio is sniffing.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4I have to mention two of the long dead Great Lesbians of flowers here; Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf. OK now that I've mentioned them you know that she knows that they knew something that I probably don’t know. But I’ll get to not knowing later. For now I’ll float the cosmic repetitions that flatten and exalt au méme temps. A rose is a rose is a rose. If you hear eros and arrows and arose here I can’t stop you and neither could Stein and DeGiulio wouldn’t even bother. A rose is not like anything it doesn’t symbolize anything it’s not representing some damn thing it’s a rose dammit it’s not just a rose it’s a rose is not more than a rose because the thing itself is enough to shatter my anxiety-addled grip on stuff. My grip on things and stuff and days and time and keeping it all under control. The show is called “Live or Die.” I’m not exaggerating here. I’m not getting all tenderhearted either though, because a rose is NOT tenderness or innocence or grief or consolation or even Bandaid. I’m going to stick to the numbers and say that I find it remarkable that roses, like eggs, come in a dozen. Same as the months in a year.

Fig. 5

Fig. 5Origin stories only matter if something needs to be considered original and it can only be original if it is relentlessly repetitive.1 This is the paradox of originality and it bears repeating. Twelve roses are consistently painted until they are thoroughly dead. Sometimes she calls them soldiers and I do get a bit choked up about that but I’m over it soon enough. Little soldiers in their clean white uniforms opening up and dying even before she sees them and seizes them and takes them home. DOA. She puts them on the radiator and mixes up some black paint and white paint and lately some dead-fish pink and desert-sunset orange and pee-snow yellow. During the years when they were just black and white and a million dreary aching grays I remember the white was always giving her trouble. Something about linseed oil yellowing, going brittle and cracked and sadder still. Safflower wasn’t much better. She made these charts and studies and read a few books even, trying to keep those whites white but yellow they would and did. Just like the roses. The bloom doth fade it do.

Fig. 6

Fig. 6There’s too much I can’t look and I can’t remember and I can't stand it, it makes me sniffly and sad. I wilt. I wilt not. At least there is respite when they lie down. I don’t think she’s ever painted them standing up so straight and tall like good soldiers. But what do I know, it’s so long since I’ve seen the radiator and the window and the white roses lying there. I know there is a piece of wood propped on the radiator and I know the roses are situated there on the piece of wood, which I think is painted white but it might be gray or maybe it changes. Maybe sometimes it could be pink. I once stole from a thrift store a three-by-five card taped to a dresser, the words “it don’t have to stay pink” in bold letters. But what if it does.

Fig. 7

Fig. 7The paintings did one day begin to blush. I faintly think I remember that day. I like to think I do, because I remember the feeling of sunset and flirting just heating up my subcutaneous layer. Shame or pleasure or just a twinge before a feeling even gets felt, that pink made me ashamed to think I ever touched anything, anything at all with all the gruff angry-sad lesbian twinges in my sorry fingers.

Fig. 8

Fig. 8There they are. All those heads, nodding, opening, drooping, singing, gossiping, bunches of chorus girls or the wives in Fiddler on the Roof. Pick me, pick me. This is what genre can do for you. Same time every week, each rectangle same size. Each painting shifting the plane. Tipping, sliding. Cezanne’s table set each morning and Laura Letinsky's aftermath each night. It’s over. When did it start?

Fig. 9

Fig. 9I admit it’s painful to think about these paintings of roses and to think of DeGiulio painting these roses or those roses or those. Picturing (in my mind, without a picture to remember, just a composite, some made-up hybrid collage of parts all mashed together to make something that sticks) there by the window in my mind, DeGiulio with a brush, touch a surface with a brush. It's anyone really, but I always picture her more Irish, all Beckett and Joyce and narrow unlit hallways and smoky kitchen tables and dirty windows and a view of the alley. These ain’t the roses you ordered eh? I don’t think she’s making it nice for you, not with that brassiere on the floor keeping it low and real for all the double mastectomies of the world tonight.

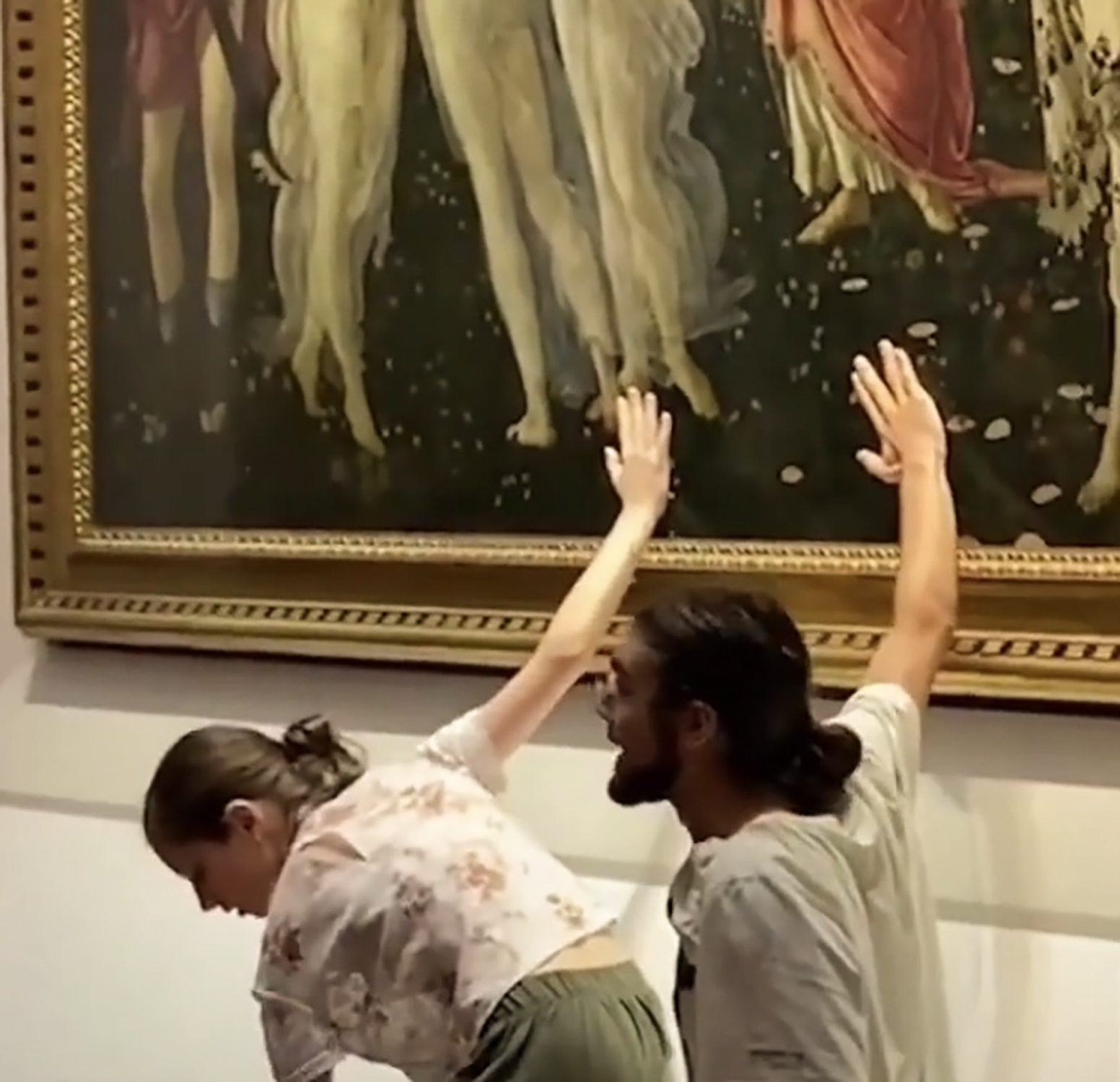

Fig. 10

Fig. 10Tonight

I’m writing this from a rented room. The “Cozy Coop” next to the chickens in the outskirts of Albuquerque to a chorus of barking dogs I can’t see, but I can hear them. I think you make the same gesture your whole life and you may only catch a glimpse of what other people see but can’t tell you about what you might be saying. DeGiulio was my first art teacher and she’s been way ahead of me for a long time.

Written on the occasion of “Dana DeGiulio, Live or Die,” Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery, Wesleyan University (February 1 through March 6, 2022).

Molly Zuckerman-Hartung is a painter, writer, and teacher who grew up in Olympia, Washington and participated in Riot Grrrl in her formative years. She attended the Evergreen State College in the 1990s and worked in used bookstores and bars until her thirties, when she moved to Chicago and attended the School of the Art Institute for graduate school. She was a full time senior critic at Yale School of Art until 2021, and is now teaching part time at Yale and School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She has shown at Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and the 2014 Whitney Biennial, among many other venues. In 2013 she received a Louis Comfort Tiffany Award. In 2021 she opened a mid-career survey show at the Blaffer in Houston, Texas, called “Comic Relief,” which was accompanied by a monograph.

Endnotes

1. See Briony Fer, The Infinite Line (Yale University Press, 2004).

All images courtesy Dana DeGiulio.

Fig. 1, Dana DeGiulio, Wet fur froze, detail. 2022. Soap on window with glue-residue of a Lawrence Weiner. Zilkha Gallery, Wesleyan University.

Fig. 2, shoe, courtesy of Dana DeGiulio.

Fig. 3, cup, courtesy of Dana DeGiulio.

Fig. 4,Danger Bird in studio, 2021.

Fig. 5, Artist's still from Show Biz Bugs (Fritz Freleng, 1957).

Fig. 6, bird, courtesy of Dana DeGiulio.

Fig. 7, Helen, courtesy of Dana DeGiulio.

Fig. 8, Nicolas Poussin, Blind Orion Searching for the Rising Sun, detail, 1658.

Fig. 9, Studio view, early spring, 2021.

Fig. 10, Artist's still from cellphone footage of a glue protest by Ultima Generazione at the Uffizi, 2022. (There was glass covering the painting, Botticelli's Primavera, 1485.)

Read next: Out Front and Down Low, an interview c. 1977 with AACM drummer/composer Ajaramu by Ted Panken