On Fluid Frontiers

By Greg de Cuir Jr

The poetics of cinema are often treated as akin to the act of

reading, with the art form itself functioning as a language or system of signs.

It has also been said that sequences of shots are not similar to sentence

structures, but rather more like music, which has its own system of writing

with signs, lines, bars, and sheets. Some

ambitious author somewhere should write an account of the history of reading in

cinema, rather than reading cinema (as writing) itself. What I will do instead

is offer a modest consideration of a profound recent film with the act of

reading at its core; a bibliophilic film and a cinematic ode to a city; an interdisciplinary

and internationalist work that tracks the trail of liberation, that foments

revolutionary awakening, primarily through a celebration of art in

Windsor-Detroit.

Fluid Frontiers by Ephraim Asili is the penultimate chapter in his multi-part series The Diaspora Suite (2011-17). He initiated it over the course of a residency in Windsor-Detroit as a commission from Media City Film Festival in 2016, and it won the festival’s grand prize when it was shown in the international competition the following year. As with all the films in Asili’s Diaspora Suite, Fluid Frontiers is shot on 16mm film. It devotes a loving gaze to Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario as key transnational points on a historical continuum of Black liberation. In fact, Fluid Frontiers might very well be the greatest homage ever paid to the city of Detroit in avant-garde film. While documenting spaces on either side of the Detroit River, Asili is primarily concerned with landmarks of contemporary art, such as The Heidelberg Project and Dabls Mbad African Bead Museum; monuments, such as the Tower of Freedom; sites of cultural heritage, including John K. King Books, Amherstburg Freedom Museum, and Sandwich First Baptist Church (Canada’s oldest active Black church) and the Ambassador Bridge, which spans the Detroit River and connects the United States and Canada. While close to a city symphony—films generally composed of a lyrical flow of visuals shot in urban spaces with no spoken word accompaniment—Asili’s creation is rather a symphony of texts, a readerly film, as Roland Barthes might have classified it, in both theme and action.

The Diaspora Suite is composed of five films: Forged Ways (2010), American Hunger (2013), Many Thousands Gone (2014), Kindah (2016) and finally Fluid Frontiers (2017). This suite represents the artist’s personal study of an African diaspora in motion, an internationalist collage of poetics of Black cultures, but the films do not necessarily need to be watched together or in sequence. Each one is an individual portrait of various cities—from Harlem to Addis Ababa, from Philadelphia to Salvador, from Detroit to Windsor—and the peoples and practices that animate them. The Diaspora Suite has screened widely in the Americas and Europe and has brought Asili to the forefront of a young generation of Black directors practicing alternative forms of cinema.

Most of the films in the Suite are visual and sound poems etched in an impressionist manner onto 16mm film. The music is often as experimental as the images in not adhering to Western notions of cadence and construction. However Fluid Frontiers departs from the pattern of the other films in the Suite and makes extensive use of recorded dialogue, of a synchronous relation between image and sound, and a more faithful deference to nonfictional representation. We should not call it a documentary, though—we tend to throw that word around far too carelessly. It is more in line with the non-dogmatic tradition of the essay film, here in both a literal and also a figurative sense.

The title of Asili’s film is derived from a collection of writing edited by Karolyn Smardz Frost and Veta Smith Tucker: A Fluid Frontier: Slavery, Resistance, and the Underground Railroad in the Detroit River Borderland was published by Wayne State University Press in 2016 and won a State History Award when it was released. The book deals with the little-known history of the Underground Railroad in the Detroit River region. Indeed this area was the final destination for thousands seeking freedom from slavery, with the river marking a final passage—certainly a passage of biblical proportions for those making the perilous journey, who had never seen, never known, another world, save for the one conjured in their prayers. The ultimate destination was Canada, a more hospitable national setting where one could survive and hopefully thrive.

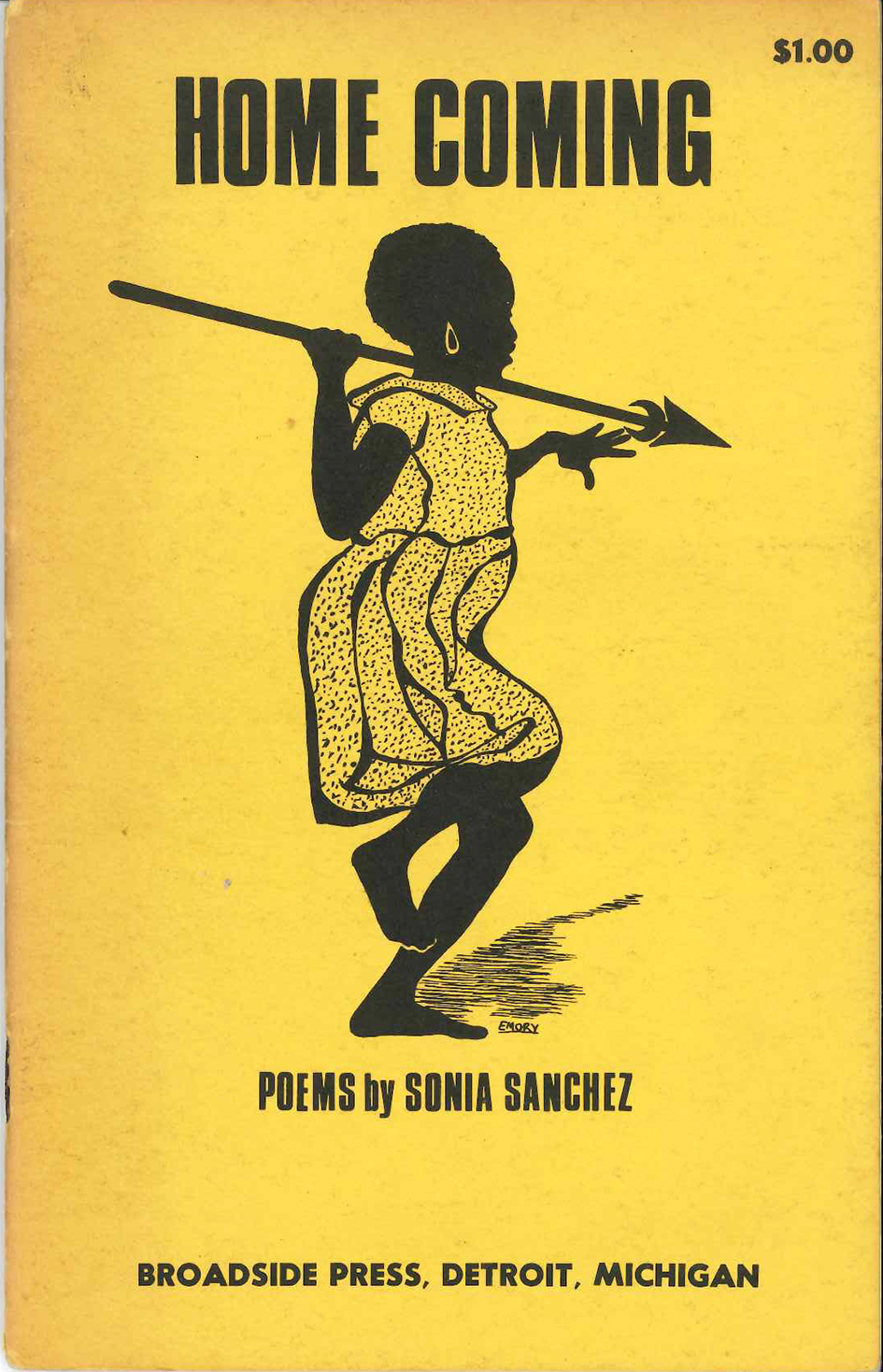

The act of reading is the main track of Fluid Frontiers. Asili stages encounters, some of them impromptu and others coordinated, with Black citizens living on both sides of the river reciting passages from the filmmaker’s personal collection of first edition Broadside Press publications. Broadside Press is a legendary institution in Detroit and should be better known internationally as a vital and trailblazing publisher of African-American poetry with over 150 titles to its credit. The press was founded in 1965 by Dudley Randall in his home in Detroit, which served as both editorial office and production hub. Like so many Detroiters, Randall worked at Ford’s River Rouge Foundry before becoming the reference librarian for Wayne County; he was also a poet and a translator from Russian. Randall’s publishing preferences, often centered around poetry, had no small impact on a brilliant generation of literary artists including Audre Lorde, Sonia Sanchez, and hundreds more (Lorde was nominated for a National Book Award for her work with Broadside).

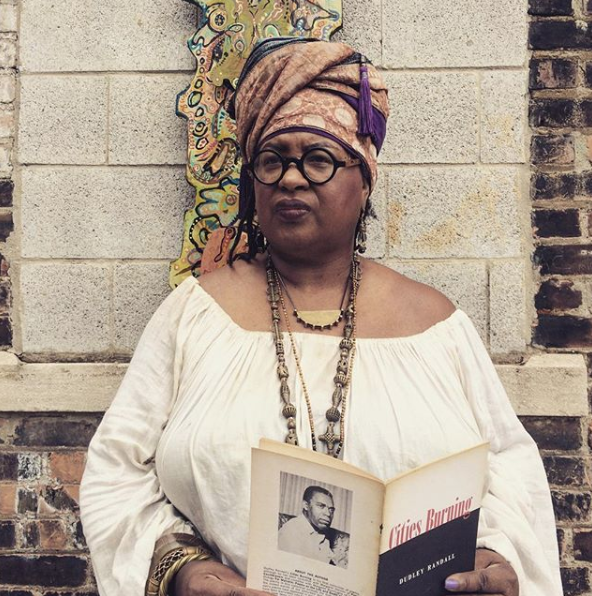

Most all of the Broadside publications are poems and essays about Black liberation and revolution, each one making its impact through a powerful rhetoric and an often overwhelming visual evocation. Consider the final poem in Fluid Frontiers, read by Marsha Music, a beloved icon in the city of Detroit, and a writer, cultural historian, and activist connected with the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. “The Ballad of Birmingham,” from the Broadside publication Cities Burning (1968), was written by Dudley Randall himself to commemorate the infamous Birmingham, Alabama church bombing of 1963; it ends on the vision of a mother standing on a smoldering heap of debris, holding her young daughter’s white shoe, and calling out into the chaos:

Fluid Frontiers depicts a colorful array of beautifully designed Broadside originals, always framed from a slightly low angle so that the covers can be fully appreciated while the participants in the film read. Asili is himself a bibliophile. He bought many of these rare editions during a research visit to John King Books in Detroit, another legendary literary site in the city, also founded in 1965 as an independent shop for rare and used books. A poem from Sonia Sanchez’s broadside, We a BaddDDD People, is read at the site by Detroiter Deborah Lee, a longtime employee of John King. In addition to collecting books, primarily about Black peoples and cultures, Asili is also a discerning collector of vinyl records, thus sound and music are also key aesthetic elements in Fluid Frontiers.

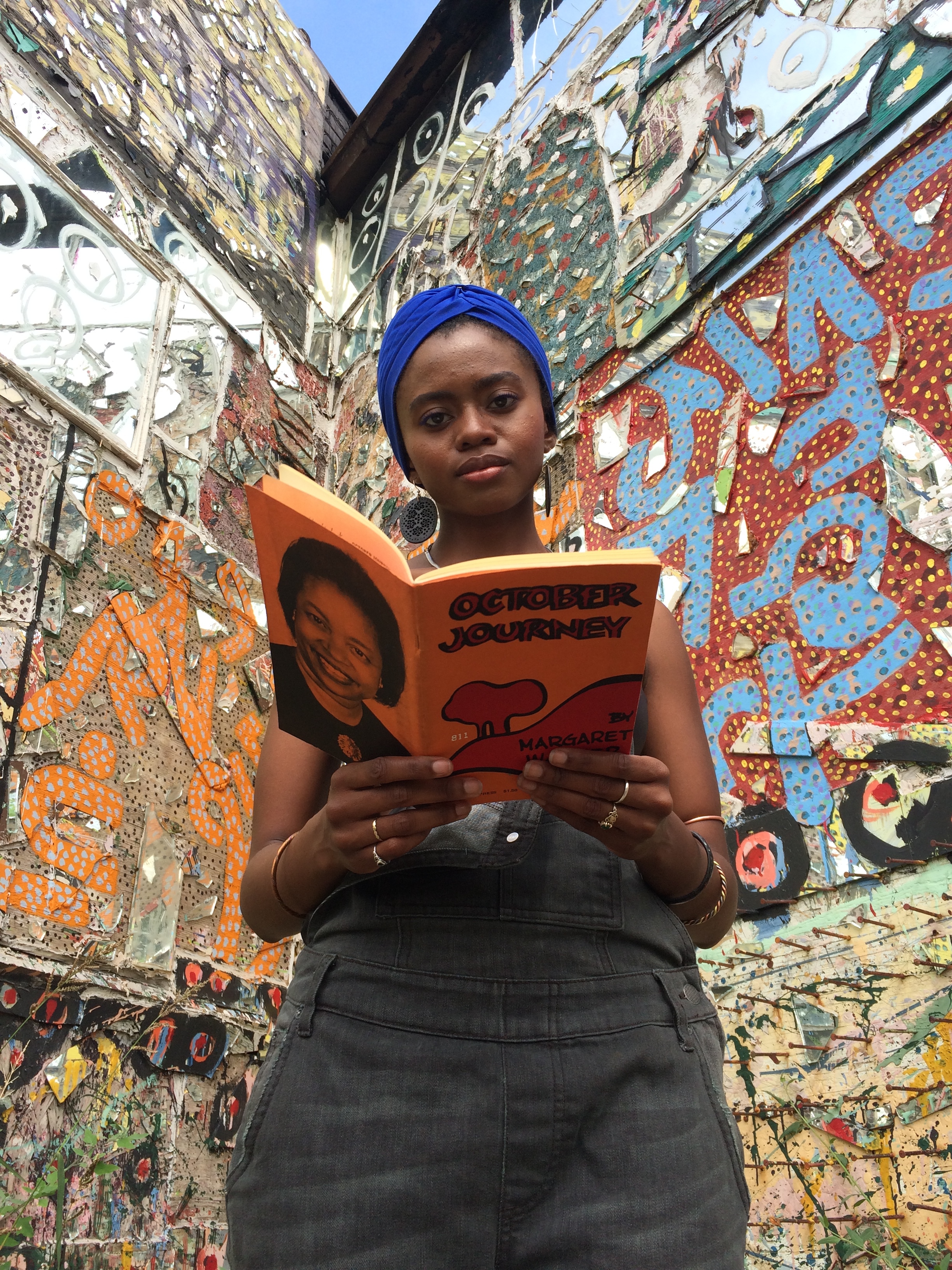

There are two main structuring motifs in Fluid Frontiers, one general and the other specific. The former is the repeated act of reading, the latter an audio recording which serves as a mediator of the literary. A vinyl record is heard in fragments throughout the film, with audio interventions undertaken by Asili via a sampler that he has employed on multiple projects. The recording features pioneering Black poet Margaret Walker reading her ode to Harriet Tubman (from The Poetry of Margaret Walker, released by Folkways Records in 1975). But Walker’s lyrical homage to Tubman was first published in the Broadside Press edition of her poetry titled October Journey (1973). We see the original publication in Asili’s film being read by local artist Jonni Page in front of the African Language Wall at Dabls Mbad African Bead Museum, founded as a space to discuss material culture from an African perspective. Immediately following Page’s reading, there is a shot of the Ambassador Bridge spanning the Detroit River, whose mighty currents once helped countless unnamed Underground Railroad operatives guide the oppressed to freedom. We might also consider Asili’s majestic shot of the bridge as an homage to his mentor, friend, and major contributor to the American avant-garde cinema, Peter Hutton, who was born and raised in Detroit, and whose practice was deeply influenced by the industrial spaces of the city. Hutton’s final film, Three Landscapes (2013), completed three years before his untimely passing, is another major work that celebrates the city, particularly through an extended shot of the Ambassador Bridge. Hutton shot Three Landscapes in Detroit after returning to his hometown to premiere his masterpiece At Sea at Media City Film Festival in 2006.

Harriet Tubman is synonymous with the Underground Railroad; she is a transcendent symbol of Black people’s struggles to reach a higher station, and the embodiment of a bridge to a better life for so many. It is not apparent who the Ambassador Bridge was named for when it opened in 1929 during the onset of the Great Depression. It is perhaps ironic that this bridge would ultimately become the most profitable commercial corridor in North America, and to this day remains privately owned. However, it is the spirit of Harriet Tubman that stands as a symbolic representation of the many hundreds of unnamed operatives who risked their lives to assist thousands seeking freedom across this river passage, and who reign supreme over the film as exalted visionaries and inspirational force. Tubman’s legacy, and the political concerns that emanate from her time, which remain relevant today, are dealt with thoroughly in Fluid Frontiers, through the art, culture, and the living heritage that continue to shape the Detroit-Windsor region.

It so happens that Fluid Frontiers also serves as a bridge to Asili’s debut feature The Inheritance, released with premiere screenings at the Toronto International and New York Film Festivals in 2020. In a similar way, The Inheritance is not a documentary, though it makes use of archival footage, location shooting, nonprofessional actors, and books. Books appear everywhere in this film, in some cases the same books and authors that structure the narrative of Fluid Frontiers. In fact the title, The Inheritance, is also a direct allusion to books, as the main character in the film is bequeathed a treasure trove of publications that deal with the history of radical Black culture. The great works of literary art presented in The Inheritance are read by the characters and studied by them. They sleep with the books, which form the primary material of the film’s art direction and its scenario (credited to Asili himself). If Fluid Frontiers is an ode to Detroit and the publications that inject a pulse into the history of the city and its environs, The Inheritance then is an homage to the insurrectionary potential of engaged literature, while training a loving eye on the city of Philadelphia, where Asili grew up. At one point in The Inheritance we see a chalkboard with a quote from African-American sociologist, author and poet Calvin Hernton. The quote elaborates on Hernton’s grand theory that the spiritual orbit and the physical orbit of things are “integral whirls.” One might also characterize Asili’s global, cross-disciplinary cinema in this way.

Near the end of Fluid Frontiers, right before “The Ballad of Birmingham” is read, there is a shot of Windsor’s Sandwich First Baptist Church,1 an important stop along the Underground Railroad, and the oldest active black church in Canada, founded in 1820. The church was constructed brick by brick, by formerly enslaved people with clay retrieved from the Detroit riverbanks. It is worth noting that all of the readers featured in Fluid Frontiers who appear in the film on the Canadian side are descendants of original freedom seekers, many of whom have been instrumental in preserving the important histories that form the subject of the film, including Irene Moore Davis, Teajay Travis, Kim Duane Elliott, Leslie McCurdy and many others. The link between the Sandwich First Baptist Church and the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, which as mentioned above was bombed in a notorious act of white supremacist terror, is therefore forged through poetry.

Sandwich First Baptist should be a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and indeed there is already a campaign underway to also designate the Detroit River, mounted by some of the film’s participants and allies, spearheaded by researcher, author, and historian Kimberly Simmons, who estimates upwards of 25,000 people crossed this river passage to find freedom in Canada. In 2018, Media City Film Festival’s director, Oona Mosna, organized a special screening event, “HOMECOMING: The Diaspora Suite on the Underground Railroad,” at Sandwich First Baptist, with Asili and all of the film’s readers in attendance. The church was packed to capacity, and the discussion that followed extended the aesthetic and political project of Fluid Frontiers in exciting ways, further grounding the film in lived experience, while also projecting it into a future in need of much more benevolence.

If you stand in the middle of Sandwich First Baptist, facing the altar, in the central aisle, you can feel the slight hollow depression in the floor that betrays a false bottom, through which an untallied number of formerly enslaved peoples escaped into an underground passage that hid them from bounty hunters, from a violent oppression generations deep, and a general social injustice still unaddressed, still growing today. Untold stories emanate from that miraculous trapdoor in the church’s floorboards, enough to fill a suite of books, a press, a library even. The essence of this space, itself a fluid frontier, represents an entire history of Black radical thought and practice, along with the beautiful and necessary art and life that flowed forth from it.

Fluid Frontiers by Ephraim Asili is the penultimate chapter in his multi-part series The Diaspora Suite (2011-17). He initiated it over the course of a residency in Windsor-Detroit as a commission from Media City Film Festival in 2016, and it won the festival’s grand prize when it was shown in the international competition the following year. As with all the films in Asili’s Diaspora Suite, Fluid Frontiers is shot on 16mm film. It devotes a loving gaze to Detroit, Michigan, and Windsor, Ontario as key transnational points on a historical continuum of Black liberation. In fact, Fluid Frontiers might very well be the greatest homage ever paid to the city of Detroit in avant-garde film. While documenting spaces on either side of the Detroit River, Asili is primarily concerned with landmarks of contemporary art, such as The Heidelberg Project and Dabls Mbad African Bead Museum; monuments, such as the Tower of Freedom; sites of cultural heritage, including John K. King Books, Amherstburg Freedom Museum, and Sandwich First Baptist Church (Canada’s oldest active Black church) and the Ambassador Bridge, which spans the Detroit River and connects the United States and Canada. While close to a city symphony—films generally composed of a lyrical flow of visuals shot in urban spaces with no spoken word accompaniment—Asili’s creation is rather a symphony of texts, a readerly film, as Roland Barthes might have classified it, in both theme and action.

The Diaspora Suite is composed of five films: Forged Ways (2010), American Hunger (2013), Many Thousands Gone (2014), Kindah (2016) and finally Fluid Frontiers (2017). This suite represents the artist’s personal study of an African diaspora in motion, an internationalist collage of poetics of Black cultures, but the films do not necessarily need to be watched together or in sequence. Each one is an individual portrait of various cities—from Harlem to Addis Ababa, from Philadelphia to Salvador, from Detroit to Windsor—and the peoples and practices that animate them. The Diaspora Suite has screened widely in the Americas and Europe and has brought Asili to the forefront of a young generation of Black directors practicing alternative forms of cinema.

Most of the films in the Suite are visual and sound poems etched in an impressionist manner onto 16mm film. The music is often as experimental as the images in not adhering to Western notions of cadence and construction. However Fluid Frontiers departs from the pattern of the other films in the Suite and makes extensive use of recorded dialogue, of a synchronous relation between image and sound, and a more faithful deference to nonfictional representation. We should not call it a documentary, though—we tend to throw that word around far too carelessly. It is more in line with the non-dogmatic tradition of the essay film, here in both a literal and also a figurative sense.

The title of Asili’s film is derived from a collection of writing edited by Karolyn Smardz Frost and Veta Smith Tucker: A Fluid Frontier: Slavery, Resistance, and the Underground Railroad in the Detroit River Borderland was published by Wayne State University Press in 2016 and won a State History Award when it was released. The book deals with the little-known history of the Underground Railroad in the Detroit River region. Indeed this area was the final destination for thousands seeking freedom from slavery, with the river marking a final passage—certainly a passage of biblical proportions for those making the perilous journey, who had never seen, never known, another world, save for the one conjured in their prayers. The ultimate destination was Canada, a more hospitable national setting where one could survive and hopefully thrive.

The act of reading is the main track of Fluid Frontiers. Asili stages encounters, some of them impromptu and others coordinated, with Black citizens living on both sides of the river reciting passages from the filmmaker’s personal collection of first edition Broadside Press publications. Broadside Press is a legendary institution in Detroit and should be better known internationally as a vital and trailblazing publisher of African-American poetry with over 150 titles to its credit. The press was founded in 1965 by Dudley Randall in his home in Detroit, which served as both editorial office and production hub. Like so many Detroiters, Randall worked at Ford’s River Rouge Foundry before becoming the reference librarian for Wayne County; he was also a poet and a translator from Russian. Randall’s publishing preferences, often centered around poetry, had no small impact on a brilliant generation of literary artists including Audre Lorde, Sonia Sanchez, and hundreds more (Lorde was nominated for a National Book Award for her work with Broadside).

Most all of the Broadside publications are poems and essays about Black liberation and revolution, each one making its impact through a powerful rhetoric and an often overwhelming visual evocation. Consider the final poem in Fluid Frontiers, read by Marsha Music, a beloved icon in the city of Detroit, and a writer, cultural historian, and activist connected with the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. “The Ballad of Birmingham,” from the Broadside publication Cities Burning (1968), was written by Dudley Randall himself to commemorate the infamous Birmingham, Alabama church bombing of 1963; it ends on the vision of a mother standing on a smoldering heap of debris, holding her young daughter’s white shoe, and calling out into the chaos:

For when she heard the explosion,

Her eyes grew wet and wild.

She raced through the streets of Birmingham

Calling for her child.

She clawed through bits of glass and brick,

Then lifted out a shoe.

‘O, here’s the shoe my baby wore,

But, baby, where are you?’

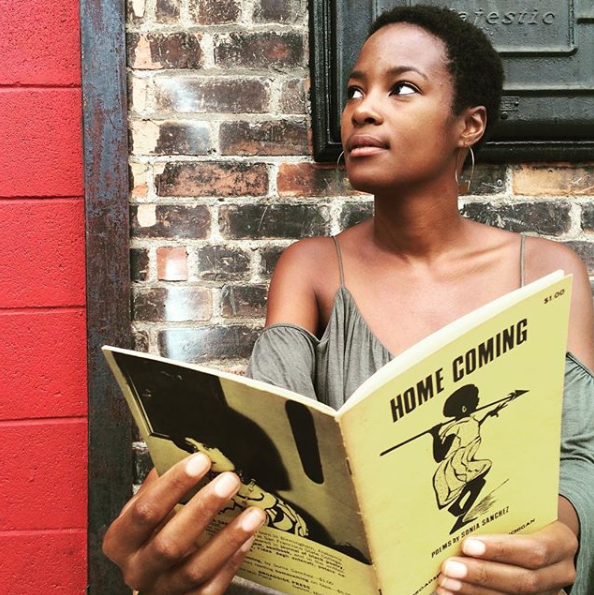

Fluid Frontiers depicts a colorful array of beautifully designed Broadside originals, always framed from a slightly low angle so that the covers can be fully appreciated while the participants in the film read. Asili is himself a bibliophile. He bought many of these rare editions during a research visit to John King Books in Detroit, another legendary literary site in the city, also founded in 1965 as an independent shop for rare and used books. A poem from Sonia Sanchez’s broadside, We a BaddDDD People, is read at the site by Detroiter Deborah Lee, a longtime employee of John King. In addition to collecting books, primarily about Black peoples and cultures, Asili is also a discerning collector of vinyl records, thus sound and music are also key aesthetic elements in Fluid Frontiers.

There are two main structuring motifs in Fluid Frontiers, one general and the other specific. The former is the repeated act of reading, the latter an audio recording which serves as a mediator of the literary. A vinyl record is heard in fragments throughout the film, with audio interventions undertaken by Asili via a sampler that he has employed on multiple projects. The recording features pioneering Black poet Margaret Walker reading her ode to Harriet Tubman (from The Poetry of Margaret Walker, released by Folkways Records in 1975). But Walker’s lyrical homage to Tubman was first published in the Broadside Press edition of her poetry titled October Journey (1973). We see the original publication in Asili’s film being read by local artist Jonni Page in front of the African Language Wall at Dabls Mbad African Bead Museum, founded as a space to discuss material culture from an African perspective. Immediately following Page’s reading, there is a shot of the Ambassador Bridge spanning the Detroit River, whose mighty currents once helped countless unnamed Underground Railroad operatives guide the oppressed to freedom. We might also consider Asili’s majestic shot of the bridge as an homage to his mentor, friend, and major contributor to the American avant-garde cinema, Peter Hutton, who was born and raised in Detroit, and whose practice was deeply influenced by the industrial spaces of the city. Hutton’s final film, Three Landscapes (2013), completed three years before his untimely passing, is another major work that celebrates the city, particularly through an extended shot of the Ambassador Bridge. Hutton shot Three Landscapes in Detroit after returning to his hometown to premiere his masterpiece At Sea at Media City Film Festival in 2006.

Harriet Tubman is synonymous with the Underground Railroad; she is a transcendent symbol of Black people’s struggles to reach a higher station, and the embodiment of a bridge to a better life for so many. It is not apparent who the Ambassador Bridge was named for when it opened in 1929 during the onset of the Great Depression. It is perhaps ironic that this bridge would ultimately become the most profitable commercial corridor in North America, and to this day remains privately owned. However, it is the spirit of Harriet Tubman that stands as a symbolic representation of the many hundreds of unnamed operatives who risked their lives to assist thousands seeking freedom across this river passage, and who reign supreme over the film as exalted visionaries and inspirational force. Tubman’s legacy, and the political concerns that emanate from her time, which remain relevant today, are dealt with thoroughly in Fluid Frontiers, through the art, culture, and the living heritage that continue to shape the Detroit-Windsor region.

It so happens that Fluid Frontiers also serves as a bridge to Asili’s debut feature The Inheritance, released with premiere screenings at the Toronto International and New York Film Festivals in 2020. In a similar way, The Inheritance is not a documentary, though it makes use of archival footage, location shooting, nonprofessional actors, and books. Books appear everywhere in this film, in some cases the same books and authors that structure the narrative of Fluid Frontiers. In fact the title, The Inheritance, is also a direct allusion to books, as the main character in the film is bequeathed a treasure trove of publications that deal with the history of radical Black culture. The great works of literary art presented in The Inheritance are read by the characters and studied by them. They sleep with the books, which form the primary material of the film’s art direction and its scenario (credited to Asili himself). If Fluid Frontiers is an ode to Detroit and the publications that inject a pulse into the history of the city and its environs, The Inheritance then is an homage to the insurrectionary potential of engaged literature, while training a loving eye on the city of Philadelphia, where Asili grew up. At one point in The Inheritance we see a chalkboard with a quote from African-American sociologist, author and poet Calvin Hernton. The quote elaborates on Hernton’s grand theory that the spiritual orbit and the physical orbit of things are “integral whirls.” One might also characterize Asili’s global, cross-disciplinary cinema in this way.

Near the end of Fluid Frontiers, right before “The Ballad of Birmingham” is read, there is a shot of Windsor’s Sandwich First Baptist Church,1 an important stop along the Underground Railroad, and the oldest active black church in Canada, founded in 1820. The church was constructed brick by brick, by formerly enslaved people with clay retrieved from the Detroit riverbanks. It is worth noting that all of the readers featured in Fluid Frontiers who appear in the film on the Canadian side are descendants of original freedom seekers, many of whom have been instrumental in preserving the important histories that form the subject of the film, including Irene Moore Davis, Teajay Travis, Kim Duane Elliott, Leslie McCurdy and many others. The link between the Sandwich First Baptist Church and the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, which as mentioned above was bombed in a notorious act of white supremacist terror, is therefore forged through poetry.

Sandwich First Baptist should be a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and indeed there is already a campaign underway to also designate the Detroit River, mounted by some of the film’s participants and allies, spearheaded by researcher, author, and historian Kimberly Simmons, who estimates upwards of 25,000 people crossed this river passage to find freedom in Canada. In 2018, Media City Film Festival’s director, Oona Mosna, organized a special screening event, “HOMECOMING: The Diaspora Suite on the Underground Railroad,” at Sandwich First Baptist, with Asili and all of the film’s readers in attendance. The church was packed to capacity, and the discussion that followed extended the aesthetic and political project of Fluid Frontiers in exciting ways, further grounding the film in lived experience, while also projecting it into a future in need of much more benevolence.

If you stand in the middle of Sandwich First Baptist, facing the altar, in the central aisle, you can feel the slight hollow depression in the floor that betrays a false bottom, through which an untallied number of formerly enslaved peoples escaped into an underground passage that hid them from bounty hunters, from a violent oppression generations deep, and a general social injustice still unaddressed, still growing today. Untold stories emanate from that miraculous trapdoor in the church’s floorboards, enough to fill a suite of books, a press, a library even. The essence of this space, itself a fluid frontier, represents an entire history of Black radical thought and practice, along with the beautiful and necessary art and life that flowed forth from it.

Greg de Cuir Jr is an independent curator, writer, and translator who lives in Belgrade, Serbia.

Read next: Measuring Time from Integral Whirls: A Dossier on Ephraim Asili

Endnotes

1. Sandwich First Baptist Church is the oldest active black church in Canada. A group of former slaves began an informal church group in the 1820s. In 1840, fugitive slaves from the Close Communion of Baptists formed the congregation. They worshipped outdoors or in the homes of individual members until a log cabin was constructed in 1847 under the direction of Rev. Madison Lightfoot. One acre of land was donated by the Crown for a new brick church in 1851. Fugitive slaves worked to construct the new church with hand-hewn lumber and bricks. The clay for the bricks was obtained from the Detroit riverbanks and fired in a handmade kiln.

The church was an important terminal on the Underground Railroad because it was situated near an ideal river crossing point. A series of tunnels and trapdoors helped facilitate safe arrival of fugitives. Individuals escaping slavery in America could make their way, with the assistance of members of the congregation, from the cellar of the church. Following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in America, slave catchers would venture into Canada in attempts to capture fugitive slaves and claim their bounty. In the event that a slave catcher would arrive in the church a rehearsed plan would go into effect. It is said that the pastor would raise the alarm by singing predetermined hymns, such as “There is a Stranger at The Door.”

The site is still an active church with a dedicated membership. Visitors to Sandwich First Baptist Church can still view the trapdoor in the floor. The church and other historically significant sites appear in Ephraim Asili’s film Fluid Frontiers. [Source: Media City Film Festival catalogue]