The Memoirs of Michael Conboy

Wiggin’ Out!

Insuppressible forces propelled me out of the house one blustery October night, forces in the guise of hormones that only a few years before had limited their power to wreaking havoc on my complexion. It was 1973 and I was nineteen going on fourteen, thanks to an adolescence delayed by time spent with too many girls who falsely believed something must be wrong with them. The time had come to break away from years of unanswered prayers and face the facts—I was into guys. And if the facts came wrapped up in a package that resembled Robert Conrad in his Wild, Wild, West get-up or officer Kent McCord from Adam 12, then all the better.

I kissed Mom goodbye and left her in the back room with her TV tray, Carol Burnett, and the sound of ice cubes tinkling in Canadian Club and water. Too many years would pass before I fully considered how she must have felt at forty-nine, recently widowed, and facing a future she’d never planned on, but tonight it was all about me.

I backed her maroon ’68 Dodge Dart out of the drive and punched at the radio just in time to catch Billy Preston singing, “Nothin’ from nothin’ leaves nothin,’” knowing in my gut it was finally time to get somethin’. The fourteen-mile journey down Six Mile Road took me farther and farther from my beige bedroom in the beige suburb of Harper Woods. It was a straight shot through Detroit, a city The New York Times had just declared “Murder Capital of America.” They’d put the chances of getting killed at two-thousand to one, apparently acceptable odds if you’ve decided you can’t wait any longer to come out. The streets that night seemed a lot more deserted than dangerous as I drove past boarded-up storefronts and weed-choked lots but precious few people. I was headed for the only place I’d heard of where the type of assignation I had in mind might have the slightest chance of taking place: a mysterious land called Palmer Park, specifically at a place called Gagen’s.

Once a vibrant neighborhood of 1920s-era gorgeous apartments, Palmer Park had struggled to hang on in the aftermath of the riots, only six years earlier. Gagen’s stood along its southern border on Six Mile Road, defiant in its deflated surroundings.

’Round and ’round the block I circled, summoning the courage to enter this strange new world. ’Round and ’round my head spun, visualizing the intimate setting I would encounter as I passed through the doors and into the arms of Ryan O’Neal or, at the very least, Bobby Sherman. Nothing had prepared me for what I was about to experience.

Gagen’s was a drag bar that had started out life in 1958 as a supper club owned by local bandleader Frank Gagen, and make no mistake about it, it was swanky! It was pretty much one big room with a bar along the right wall, and a raised dance floor at the rear with a stage behind it. The bulk of the space was filled with circular red leather banquettes. In the ceiling over each was a concave circular depression covered in gold leaf and lit indirectly—very moderne and very plush. Truth be told however, by the time it had ceded to the reign of the drag queens, it was pretty worn around the edges. A closer inspection of those banquettes revealed more than a little red carpet tape enlisted to keep it all together.

But the decor was only part of the magic. When you filtered the experience through the eyes of a determined but terrified boy who was finally attempting what David Bowie had been urging (turn and face the strange ch-ch-changes), it was like the club scenes in Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge, complete with whip pans, manic editing, and breakneck sensory overload. A red and gold explosion of music, dance, and theater.

That first night, after several beers, I calmed down. And after a few more, focused in on what looked like the man of my dreams. How was I to know this god among men was really a beauty school graduate from the equally beige suburb of Clawson with absolutely no finesse when it came to romancing a nervous virgin. Coming out lesson number one: True love and sex are not the same thing.

Whether it was my pent-up libido or my newfound love of the bizarre, I couldn’t get enough of the place. Sunday nights were smokin’ hot with a line-up of drag queens that included the likes of Buttons La Walker, Jennifer Foxx, and Betty Clarke. Miss Clarke could be seen roller skating through the crowd in a ’40s-style swimsuit, sipping a goldfish bowl-sized Cuba Libre, while singing (well, lip-synching) “Rum and Coca Cola” by the Andrews Sisters. People went wild over the spectacle of it all. Afterwards, Hummin’ Helen sang Patsy Cline’s “Crazy” in a nightgown as she dragged out an ironing board, plugged the iron into her head full of curlers, and proceeded to use it on the hem of the very rag she wore.

A major showstopper was Sharene Dennis singing a wicked version of “It Should Have Been Me” by Yvonne Fair, a wrathful screed about watching your man walk down the aisle with another woman. As the song reached a fevered pitch, Sharene would move into the audience, pull a knife from her purse, and brandish it at the imaginary couple. One night she got so worked up she tore the wig off her head and threw it into the crowd. This unheard-of act of improvisation proved too much for the aging emcee, for whom illusion was paramount. With microphone in hand, he fired her on the spot. The rest of the girls recognized Miss Dennis’ actions for what they were, an uncontrollable act of passion fully in line with the sentiment of the song, and tore their wigs off in a show of solidarity. After all the screaming and crying had ended, the emcee was forced to apologize. Hell, hath no fury!

I waited tables with Hummin’ Helen (a.k.a. Bill) at the Roostertail night club on the Detroit River while I was in college. He was a sly and amusing guy out of drag, but a real handful in character. Through this connection I found myself escorting him to an awards show for female impersonators. The affair was a brave attempt at elegance, given its location at the United Dairy Workers Hall, a cinderblock building in some empty industrial neighborhood alongside the railroad tracks. I confess I was a bit embarrassed; watching drag behind closed doors at Gagen’s was one thing, but escorting a six-foot-tall glamour puss with impressive deltoids and a fearsome baritone to a sold-out extravaganza, no matter how clandestine, was a bit much for my uptight suburban sensibilities.

True to form, Helen got loaded, fought with the other girls, and passed out in my car on the way back to her apartment. Much to my horror, I discovered the gas tank was on empty. At two in the morning, I coasted into a Sunoco station in the vicinity of Hamilton Avenue and Grand Boulevard with only a prayer that my date would remain comatose in the passenger seat, bouffant bobbing, dress up around her knees, bucket between her legs. The attendant, an older gentleman with the kind of manners learned from an age past, couldn’t help but notice my stylish powder blue tuxedo (I forgot to mention that?) and the uncertain mess slumped next to me. In an embarrassed attempt to make sense of it all, he said, “My, my, that sure is a pretty lady you got with you.” To which the pretty lady, lifting her head up in a sudden burst of consciousness replied, basso profundo, “FAAAAAAAACKYOU!!” before collapsing back into a swarm of organza.

It’s no secret what killed drag in Detroit. In a word: disco. I remember the night, just a couple of years later, when my newfound friends and I decamped from Gagen’s and walked a few doors west to check out the opening of a new place called Menjo’s. It had a deejay, state-of-the-art sound, flashing lights, and a sparkling mirror ball! A magical palace, built for dancing. Menjo’s would have a few drag shows now and then but it was definitely not about drag. All that Judy Garland lip-synching had been unceremoniously dumped in favor of KC and the Sunshine Band.

Stripped out and painted black, Gagen’s eventually went on to gain greater fame as Bookie’s Club 870, the premier punk club in Detroit. I guess all that art deco decay had no place in a new wave world. Sometime along the way it burned to the ground and maybe that’s okay; the building, like the entertainers it housed, might best be thought of as some great illusion, the likes of which Detroit hasn’t seen since.

Tonight’s the Night

Before the Q-Line stop at Baltimore, before “mixed use” became a thing, and well before the name Milwaukee Junction sexed up the area, the Woodward bar sat on what was a rather forlorn block of Woodward Avenue, just south of Grand Boulevard. By day, straights from General Motors headquarters and the Fisher Building walked in off Woodward for a highball and a burger during their lunch hour. By night, an unmarked door off the alley was the point of entry. While one might think such a covert entrance must have had SHAME written in red neon overhead, it felt more like the door to a secret realm of possibilities—no straights allowed.I started going there around 1974. I’d like to tell you I was underage but I’m trying to be unflinchingly honest in my writing. At least I can say, in the wisdom of the enlightened politicians of the era, the drinking age in Michigan had been lowered to eighteen. And I believe it’s safe to say, I was chicken.

Upon entering, the door would slam in announcement of the latest arrival. Emerging from a short darkness into the bar area, one found the entire place eager to see who it was. My entrance and that of any number of the younger crowd would provoke Andy Karagas, the fifty-something-year-old, Greek American owner to shout out in his gravelly voice, “HOT NUMBER!”

I always met this greeting with a thin smile. I was young and nervous and leery of attention, all the while, fiercely wanting it. As the years went by, Andy’s cries of “HOT NUMBER” seemed to carry less and less enthusiasm. Whether he became tired of his own shtick or I became less and less a hot number won’t be debated here, but his great personality never wavered. We all loved Andy.

Another famous line of his was, “TONIGHT’S THE NIGHT” which he’d bellow at any random moment, giving us all a sort of cheer of encouragement.

On the weekends, a middle-aged waitress called out, “ANYBODY WANNA?” then paused before finishing up quietly with, “drink?” thus clarifying her intentions. She had the kind of hair that earned her the nickname The Governor after Ann Richards, governor of Texas at the time, and proud owner of a sky-high Lone Star State beehive.

If all this sounds corny, it was. They knew it and we knew it and that’s what made it so great. In the typically overheated, sexually charged atmosphere of any gay bar full of horny little twenty-year-olds, a little comedy goes a long way in defusing the tension.

As much as Andy made you feel welcome, he was wise to the draw of a handsome boy behind the bar and there were more than a few over the years. The one that has always stayed in my mind was Robbie. Robbie, of the long curly hair long after anyone had long hair. Robbie, of the angelic face and languid eyes. Robbie, of the gentle but masculine demeanor. When I first crossed the threshold of the Woodward, I knew: If he was gay, then it was okay to be gay. When Andy yelled, “HOT NUMBER” in my direction, all I could think about was, did you hear that, Robbie? Did you? I’m a hot number! Never mind the phrase was repeated over and over with every new arrival. At the age of nineteen, I was drinking Old Grand-Dad bourbon and water because my dad drank Old Grand-Dad and water. At the Woodward they were ninety cents a piece. My memory is clear on this because I used to sit in Robbie’s section, staring love-sick across the bar, drinking one after the other until I had ten dimes in change lined up in front of me. Sadly, un-proposed to, I left him with that whopping tip and pointed myself in the direction of the car. Night after night this played out, but I was never able to convince my Adonis to rescue me from the well of loneliness.

Back then I fell in love every other day, but of all the boys I felt completely lovesick over, few came close to Robbie. Living life fully means puppy love, infatuations, and having your heart broken. And—even though it’s unbelievable at the time—getting over it and moving on. While writing this, I inquired about Robbie through old friends only to find he had died a few years back. He couldn’t have been more than fifty.

A quick Google search will tell you the Woodward lives on today catering to a gay African American crowd. The bar itself was never anything special, just two narrow rooms and a few tables; it was Andy and his crew that made the magic happen. Wouldn’t it be great to think that on any given night, the current owner is giving some insecure little newbie a shout out of “HOT NUMBER!” and letting him think for just a moment: Hey, maybe I am!

East Side Story

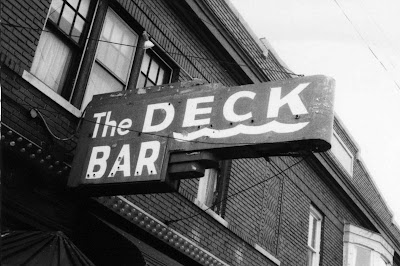

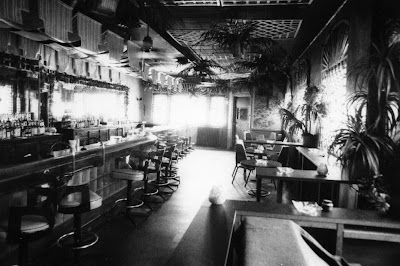

The Deck occupied an old, two-story, brick building that had started out life in the early 1900s as a local bank. The front door had a little window with one-way glass and a buzzer-controlled entry. Inside, the room was long and narrow, with a heavy wooden bar running down the right side and a row of small tables along the left. In the back, it opened onto a nice little outdoor patio. Upstairs, Pete the manager lived in one apartment while Don, the owner, used the other to entertain. It had been a long-standing neighborhood joint before Don dolled the place up with lattice-covered windows and wallpaper with a sort of forest floor theme and declared the place gay.

When I worked there, the old crowd of straight locals, mostly retired, would still gather on afternoons to drink cheap shells of beer. Among them, Miss Beverly had been a sales lady at Jacobson’s, Don had worked at Dodge’s while his wife Marge kept house, and Chuck still worked at the party store two doors down. Chuck was a fifty-five-year-old stock boy who, despite its higher price, drank his first beer of the day out of a bottle because his hands shook too much to hold a shell. They all looked forward to an appearance from Jean the bookie as she made her rounds of the nearby watering holes along Jefferson.

They filled the place with gossip and laughter until 5:15 p.m. when the gays trickled in after work, hopping off buses from downtown. The daytime regulars would look at each other with a wink and say, “Time to pack it up, darling.” Off they’d go, wobbling down the block to their apartments up and down Alter Road.

Weeknights were never too crowded: blue-collar guys turned on by a pair of khakis and a Polo shirt mixed with Grosse Pointers in search of a working-class hero. On weekends the place was jammed with Topsiders, Brooks Brothers, and Polo. Ralph Lauren had recently reinvented the preppy look with his Polo wear and the insular world of the Ivy League had never seemed so accessible. At the same time, while not exactly out, gays were certainly feeling an energized sense of community.

Being the only gay bar in the area meant that if you lived on the east side and were just cracking open the closet door, you’d probably do it by checking out The Deck. From my perch behind the bar, I witnessed many a quiet night when a terrified young guy would sit nervously apart from the rest of the customers. It didn’t take long before there were half a dozen drinks in front of him, paid for by a hopeful group of regulars. If he made it out of there alive it was on the arm of some old player who knew best how to pluck a chicken.

One night, after I’d just started my shift, a young Grosse Pointe kid came in and asked for a middle-aged regular by name. Taking him for a friend of his, I said I hadn’t seen him. The kid turned red and replied in a fury, “I knew he came here. I’m his son. Tell him never to come home again.”

It broke my heart.

Like most gay bars, the place had its day and then it passed. Attempts were made to extend its popularity: drag shows, piano players, Sunday brunch, but after a short stint as the “in” place, it settled back into life as a cozy neighborhood hangout. This life too, must have run its course because the last time I was in Detroit, The Deck had been torn down, the land awaiting construction of a cultural center. Odd, isn’t that exactly what The Deck had been?

Photographs of The Deck, Detroit | Michael Conboy

View next: Menjo’s Drag, inside When Life Was a Gay Bar, a Dossier by Michael Conboy