Making a Making

Jonathan Rajewski in Conversation with Bill Dilworth

Adjacent to a cairn of stones, each stone having been placed by innumerable pilgrimages to the site of Henry David Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond, a sign reads:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life. And see if I could not learn what it had to teach and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.–Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau understood that earth is a teacher of infinite lessons. That dirt is a fount of knowledge. When I think about Thoreau—who, after gazing at the pale, yellowish-green eyes of a heron, imagined his own soul a “bright invisible green”—I think about Bill Dilworth, receiving the sagacity of dirt. For the last 31 years, Bill has been the caretaker of Walter De Maria’s Earth Room, a second floor loft on Wooster Street in New York City that has been filled with 280,000 pounds of earth since 1977. It’s a room of dirt, what De Maria plainly called “an interior earth sculpture,” that beyond being a room of dirt, sounds and smells. The sound is stillness, performed by the dampened insulation of soil. The scent is subtle, earthly petrichor. Or mud. And Bill cares for this dirt, occasionally watering and tilling the damp earth with a triangular five-tine rake, and watching it absorb time slowly as he and everyone else does. The rest of New York loudly flutters around this placid room of dirt. An occasional mushroom sprouts, quietly among the shadows, hidden around the corner from the natural light entering from the windows facing Wooster Street.

It’s not just this room of dirt, where Bill’s care has been directed for over three decades, that makes me think of him, but his ongoing relationship with nature and time and the messages received. For Bill, soil is both metaphor and matter (of fact), of the life-bearing stratum on which we all depend. It yields, as Thoreau understood nature to yield, things to be learned.

Since 2014, Bill and I have maintained a spontaneous zig-zagging conversation. The last time I saw him was at the Earth Room, when I first experienced De Maria’s quiet monument. Between April and November of this year we continued, with distractions, a meandering dialogue in quarantine through email. Bill was in the Adirondacks with his family, taking leave from New York City, and working on an exhibition in Nebraska, while I was in Hamtramck awaiting the birth of our first child, becoming a father, and imagining a Thoreauvian trip to the woods, or even the Earth Room, that remains fantasy.

–Jonathan Rajewski, Three Fold Visual Art Editor

Jonathan Rajewski [JR] Hey Bill, I'd like to begin with the time you spent in Detroit and how you eventually ended up in New York City. When we first met in 2014 at Jack Hanley Gallery, it was by way of a couple of Cass Corridor artists, Jim Chatelain and Douglas James, who also left Detroit for New York at other points. You’ve been in New York a long time, but how did you find yourself in the Cass Corridor?

Bill Dilworth [BD] Let’s go Jonathan … Starting, let’s go back, back, back. I was born in Detroit in 1954. I moved to Chicago for a year then to Cleveland until I was three. Then back to Detroit for 20 years. Grew up on the northwest side near Six Mile and Grand River converging. A lot of kids, the block our world. Showcase car dealerships Mulligan Mercury and Emmert Chevrolet on the next block. Playing baseball on a small field some summers barefoot. If you pulled your swing and sent the ball foul left you had a good chance of putting out one of the windows in Mulligan Service Center’s wall of windows. Whoever hit it would chase the ball inside and whatever worker caught up with it would hand the ball back and we’d continue playing. Triple-headers. My mom once took my brother David and I to see the Tigers play the Yankees. It was at the time the longest game in baseball history. Twenty-two innings. We got tired of it and got on the bus to go home but the bus driver wouldn’t go until the game was over. We sat in the bus for a while. Boredom has clouded my appreciation for the game ever since. Hardball in Stoepel Park. Our little league sponsor was Nimrod’s Gun Shop on Grand River. Playing shortstop and third base, I liked light bats that swung fast and broke easy. I struck out a lot. I liked swinging. Back on the bus. My mom took David and I to Bob-Lo Island right around the time the riots broke out. We didn’t know. Until we got on the bus to go home and picked our way through a war of rage being waged. I remember for days peering down Grand River and seeing tanks in the distance. The glamor of the American automobile got tangled up in that. I had reason to think there was more to the story.

High school I walked every night and named trees. Dutch Elm disease hit hard and obliterated a lot of them. My street, Vaughan, was a tunnel of trees that was cut down in one day. White flight swept through our neighborhood like slow-burning fire. We stayed. I went to Wayne State University [WSU] for college and loved it. My parents hung in. Too long. The Earl Flynns and Coney Onnies ganged the northwest. The neighborhood ran down, to somewhere it hadn’t been. Wayne State was my salvation. Most of my friends went to expensive colleges and had to work summers. Wayne State, being inexpensive, afforded me the opportunity to spend summers in Grand Teton National Park. I only had to make enough money to fly. I was always the artist. It was something I identified with, from whenever a kid identifies with anything. I was the kid in grade school pulled out of class to make up signs celebrating the new pastor. I could choose helpers and chose those who could assemble a basketball out of paper and tape. We’d surreptitiously play for hours. I was always making art.

I almost went to Cass [Cass Technical High School] for high school and almost to Olivet for college. I went to Wayne State University for art. Pat Quinlan was a neighbor of a friend of mine, taught figure drawing at WSU and encouraged me to go. I loved it from the start. I met my future wife, Patrice Haupert, on my first day of Jim Nawara’s drawing class. I remember what she was wearing that day. Precocious, I talked my way into a printmaking class without prerequisites. Enthused, I read Gabor Peterdi’s definitive book about printmaking in one night. The only book I’ve read in one night. The next day and thereafter my stomach turned whenever I walked into a printmaking class.

I turned to painting. John Egner had been on sabbatical my first year. I met him and he asked me to help him install his sabbatical show. I felt like I was on the inside of something. That thing was the Cass Corridor art scene. A lot of my teachers were in it and a lot of people I came to know were in it. I was a student. They were a big part of my education. Influential teachers were Jim Nawara, Steve Higgins, and David Becker for drawing. Bob Hanamura for design. John Egner, Bob Wilbert, Rick Vian, and Tom Parrish for painting. I used to like to take night classes. I kept a window open in the basement of Old Main that I would slip into any time and up to the big top floor painting studio. Egner showed me where that key was stored, over a door midway on the third floor hall. At two in the morning the busride home that took an hour in the day, took 15 minutes. The bus roared. So what did I find there? What was the Cass Corridor art scene? Who knew? It was a thing that was happening at the time. Seemed vital if not defined. More manifest than manifesto, it validated making, invited commitment and shared enthusiasm.

A bunch who were living downtown, some who had recently been WSU students, stayed around to shape it. Ron Morosan, Jim Chatelain, Steve Foust, Doni Silver, Robert Sestok, everybody in the Forsythe Building of studios. I took a creative writing class with Faye Kicknosway that Brenda Goodman was sitting in on. Brenda and I became friends. One day our painting class visited Michael Luchs at his home and studio. He said something like ‘there are no diagonals in nature’ and I dismissed him as nuts. Wasn’t until years later, when he had moved to New York for a little while, that we became friends. I grew to like Luchs and admire his art. Even began to understand and very much enjoy his funny, fierce garbled wit. I took over his studio on Canal Street when he went away for a little while. He never came back.

I worked at the Detroit Institute of Arts the year after I graduated from WSU, living on East Palmer. But everyone then, having had a taste of what it really meant to be an artist, wanted to go to New York. Patti had gotten into the Yale School of Art’s graduate program for painting and I left Detroit moving to New Haven to be with her and so that we could, together, step closer to New York. We married in July ’78, travelled the U.S. in a Karmann Ghia and spent spring in Europe before moving to New York in 1979. What was it about New York then? Like Detroit, it was tough and edgy. But where Detroit stayed rough, New York got wild. If Detroit had a fissure of art emanating, New York was exploding with it. Detroit was dragging its feet while New York was out of its head. Detroit was driving to the bottom, when there seemed to be no roof on New York. It was easy to go from Detroit to New York. How could anyone coming from downtown Detroit be intimidated by anything? We were prepared.

[JR] In many ways, you and your wife Patti both have the jobs of dreams. You’re both caretakers of secluded minimalist monuments, Walter de Maria’s Earth Room (1977) and The Broken Kilometer (1979). You’re both artists, both resisting the entropy of another artist’s work and idea. You were watching over New York City’s oldest hand-wound clock, and before that, maintained La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s Dream House. I love that your business card reads, “Keeper of Earth and Time.” What is it like to sustain a work, to try and keep it static, when the world is anything but?

[BD] Takes some days consideration on her part but Patti is willing to respond about her decades-long experience at The Broken Kilometer. I am always an easier target, as you can tell, though I think the smartest people say nothing. My vanity causes me to blunder forward with words; not in the language I would prefer to speak. So I am willing, it seems, to be awkward. To what end I can’t say. At best I imagine myself talking to my great-grandchildren, marveling at that possibility to glimpse some hereditary mind in kind. Say you are looking at stars and wondering how you might connect. Maybe this, digitally preserved, will be evidence of at least precedence. I offer it as a meager gift to someone who might choose to hear it decades from now. In our time, I don’t presume to compete for anyone’s attention. I commiserate with the future’s yearning for wakefulness. The language I would prefer to speak is a visual language and that stuff (I’ve done a lot of it) may remain. Or it may not. Makes no difference to me. I do it anyway. In the meantime I strive in the present to be worthy of the future, challenging the future to be worthy of my present. All I am saying is that I’m willing to say I am here, have been here a while, have experienced some things, and have hope for the future.

I’ve been caught up most recently diving headlong into the digital exhibition with Mike Nesbit in Omaha, Nebraska, at Maple Street Construct. I hope you’ve had a chance to look at it. Turning back to our conversation, let’s continue where we left off. When we moved to NYC I got a small job pickling the floor of a giant loft on Broadway that was Sylvia Stone’s studio. She was a fairly well-respected sculptor showing at André Emmerich, doing plexiglass sculpture, some of it big. And she was married at the time to Al Held. I became her studio assistant, working for her in NYC and in Boyceville, New York, in the Catskills, where she and Al had an old dairy farm and had converted the barns into living and studio space. Their assistants stayed in the old farm house. Al had a lot of assistants that Sylvia referred to as “his brushes.” Al was physically incapable of making his own paintings because they required care and precision and he was an ape. I came to know them both well. And I preferred Sylvia. Because they fought bitterly I saw more than I felt comfortable with and so moved on to work for Dia and the Dream House as soon as I could.

Fig. 3

Going from Dream House to Earth Room was like waking up on my own planet, where I could build my own world of art. At the time, I had two young children and renting a studio on Canal Street was a stretch. Given what little time I had to be in the studio made it more of a stretch. There was a room in the back of the Earth Room that was not being used and I was happy to take that on and it has been my studio for 31 years. So I spend a lot of time there, maintaining it and maintaining myself. Mutually sustaining, I saw from the start that it provided for a unique existence and wonderful balance to life in the city. To become the “Keeper of the Earth Room,” to be the guy who waters and rakes it and opens and closes it became my way of life. The Earth Room itself is about earth, art, quiet, and time. All good things. Add to that, studio space, and why would I go anywhere else?

The few people who had the job before me may have left being more ambitious about their own art careers. I was more ambitious about my life. It afforded me a lot of time to spend with my family and to make art. Already by that time I had found my family and my own art more compelling than the people and art I was seeing in the New York City art world. Satisfied as I was with my life, having an art career didn’t seem all that necessary and so when it didn’t come easy, it was easy for me to disregard it. And the Earth Room positioned me on a promontory on the edge of the art world. Plainly visible, I saw it as not at all alluring. I think too I became sort of hooked on the freedom I had in the studio. Answering to no one, living comfortably, I was able to go wherever I wanted to go in the studio. In time, I built my own world of art. And eventually, my own marginal art career.

The Earth Room has been my livelihood and companion throughout. I know it better than anyone. Having witnessed many thousands of reactions, I am its biggest fan—my experience as big as all those reactions combined. There is something fundamental about it. You can start your searching there. And you can stop your searching there. It is immensely satisfying to have a personal relationship with a monumental work of art. It shares its bigness. And the quiet of the Earth Room is extraordinary, continually honing the senses and nurturing sensibility. And time, as measured by time, only achieved by time, grows constantly at the Earth Room.

[JR] I’ve been thinking about what you said earlier, that you “commiserate with the future’s yearning for wakefulness,” and how this wakefulness seems uninterrupted for you and your relationship with the Earth Room, that it continuously provides an infinite re-readability of space and time, in your own life and beyond. I’m interested in how you’ve described the Earth Room as life itself—“about earth, art, quiet, and time”—and how through it you became more ambitious about your life. I wonder if you could say more about it, how that emerged?

[BD] Big question, Jonathan. It asks about how one reaches for, arrives at, and maintains re-readability? Asks about the basic tenets of life itself and the ambition of reaching for, arriving at, and maintaining engagement in life? The pandemic, glaring systemic racism, and consequent pandemonium have slowed my response. I see what stood tall has bent and shattered. See the rend in rock; cleft and hew. Feeling weary in the ruin of Trump America, I walked up a mountain, looking for beyond. And cleared my mind to answer.

The answer is, because I had children. Allow me to elaborate. I was 35 and had just started working at the Earth Room. Had just begun to be grounded by it when I went to an opening at Daniel Newburg Gallery on Broadway with my wife and two young daughters. I was trying to find my way into the art world when I found my way more deeply into my children’s world. It was an opening for an artist “friend” of mine. I put that in quotes because I soon had reason to temper that friendship. He was one of a group of artists I had befriended who had made some strides in the art world. He was showing large roughly-woven mats made from blown truck tires gathered on freeways. It stunk. I’m not sure I mean that as a critique. Certainly all that shredded rubber smelled bad. Mingling, I overheard another artist friend, who was actually more of an acquaintance though we had both worked at the Dream House, who was emphatically asking another artist; “Yes, but does he have a market!?” As I listened I became confused. I knew him to be a stutterer, but here he was smooth and slick, talking business. I looked around. Though I had traded art with a few of these artists I knew I had nothing to offer for their careers and those friendships faded. They faded for me in that moment when I turned to look at my children and never looked back.

Not that the art world was bad, but that it was a struggle. Young artists were desperate to emerge; to be somewhere they weren’t. I saw something else when I looked at my children. Riveted, I saw a more pure and uncomplicated presence. I saw them as a gift. A way to be fully engaged in the present with them. To share their wonder. It was less a choice than a revelation. I simply, naturally turned to what I saw to be good. Make no mistake, raising kids is hard but if you’re trying to be a good parent you become fluent by immersion. In the same way you teach them to speak your language they teach you to know theirs. As each child seems to recreate the world, having their own worldview, they open new worlds to anyone paying attention. Instead of wanting something I didn’t have I saw my world as full.

Add family to earth, art, quiet, and time and you have the basic ingredients of a particular sensibility. Add freedom to make the art you want to make. To make art is to visually translate your sensibility. By making your sensibility visible, your mind doesn’t have to hold onto it. So art making frees your mind. I can’t think of anything more ambitious. Art becomes a means of transport. An artist is an explorer. To view the work is to be shown a path with signposts.

This I believe: that the free, exploring mind of the individual human is the most valuable thing in the world. And this I would fight for: the freedom of the mind to take any direction it wishes, undirected. And this I must fight against: any idea, religion, or government which limits or destroys the individual.

–John Steinbeck

This conversation has me wondering about my affinity for earth. Why was I so easily taken by the Earth Room? Maybe more revisionist history than revelatory truth, when I was an art student at Wayne State University in Detroit, I made and buried some paintings in my backyard. Not thinking to lay them to rest; it occurred to me to use the earth as material. I was hoping to activate and energize the work. I put the paintings underground and left them for weeks. I too was searching for the fundamentals and waiting for them to show themselves. Excavating, I looked to see what kind of interactions took place between my intent and what the earth might give me. There was some staining. But it was too subtle for me at that time and I stopped doing it. But I had those thoughts of earth as a partner. A source material. All that may have subconsciously flooded through me when I accepted the job there.

Fig. 5 and 6

[BD] Earth bears our lives as we do earth’s. We extract our being from it. Born on earth, we’re of it. But the wider universe might have a hand in our making. Stardust may be celestial pollen. Dying, we either go up in smoke or are interred within earth. Our time on earth is extended by our progeny; our children, the closest we’ll get to immortality. Earth goes on with or without us, in myriad ways, persevering. It’s natural for us to try to learn some of those ways, to preserve ourselves.

I think it’s common for artists to channel natural processes making art. Especially abstract art. To be bluntly analogous about it, you want something like fire to heat things up as you work; warming, even dangerous. You throw water on flames when things get out of control; then flow. You juggle all that, throwing it all in the air but trying to control it at the same time. You gather what you can find about fundamentals, mimic creation and become a creator. I suppose the closer you come to understanding how nature works the better you are at mimicking it and the better a creator you become. Oriented to natural truths, you make art to replicate natural truths, and by that to better understand, emphasize and celebrate them. An artwork is finished when it looks like it belongs. And as nature transforms and does not “possess,” a finished artwork is claimable by anyone who sees it. Their seeing is evolutionary.

Thinking of a finished work as the destination of a trip, for Maple Street, Mike and I highlighted the journey, exploring the making, not looking for the result. The month of April, that time, became a platform for discovery. A trip without a destination. That time was what we were investigating. Gaming the endeavor itself is to play with creation without the pretense of being the creator. So, to answer your question, yes, making a making is, I suppose, directing attention to what I perceive to be those natural processes mustered in creation. It’s trying to be honest about what you think is true.

[JR] What are you doing now, up in the Adirondacks?

[BD] The sun shines here and I can imagine myself having escaped from the shadows of the seething rage of politics and the bestial gaze of the pandemic. So I can focus a little better and maybe see plainly. The air is clean here and remarkably clear. So I can breathe easier. We have an old farmhouse that we have transformed over 24 summers, a stunning view, and a beautiful studio. Built in 2005 primarily for Patti because I have the studio at the Earth Room. Wayne State was better than Yale and she stopped painting when we had kids. Kids are better than anything. The studio up north was so that she could return to painting. But she had grown to become a phenomenal gardener and so while the landscape has blossomed, the studio has been quiet. It was understood that it would ultimately be some kind of shared studio space and with the onset of quarantine and the project handed to me by Maple Street Construct in April I took it on, launched High Peak Monocacy on May 1st, hitting a groove and have not let up.

So I’m continuing to work on the house and land and am working in the studio. It all seems like the same thing. In June, I painted the trim on the 28 windows of the studio and house. A few of them needed it but it was all done really for the color. And doing whatever I can to shape the land seems like drawing on an immense scale. High Peak Monocacy began things that I continue pushing along. Some finished painting has come from it now. Toward the end of The Keeper of Earth and Time, the small film by Tiantian Wang, I recount how someone once asked me if I thought of taking care of the tower clock as part of my art practice. I think my life is my art practice. That’s the unifying element to all the things that I do. That’s the long answer to your question. The short answer is I’m practicing.

[JR] I like that you think of shaping space as drawing on an immense scale. And like you, I think this concern with where does art stop, or where does life no longer resemble the practices of artmaking, is the wrong concern, and an especially blurry one too, if our eyes remain open and we untether ourselves from tightened definitions and borders around ideas of what is constitutive of art and making. I’m wondering who are some of those influences that shaped you, where you are now, in ideas, life and work?

[BD] My short list of favorite artists has always had de Kooning. For the evidence of what color and motion can do. Always, too, this caveat, in his words: “Don’t mistake the stars that you steer by for your destination.” He struggled to navigate beyond Gorky. And did. I don’t want to get past de Kooning. Too much fun to attempt to experience what he might have experienced painting.

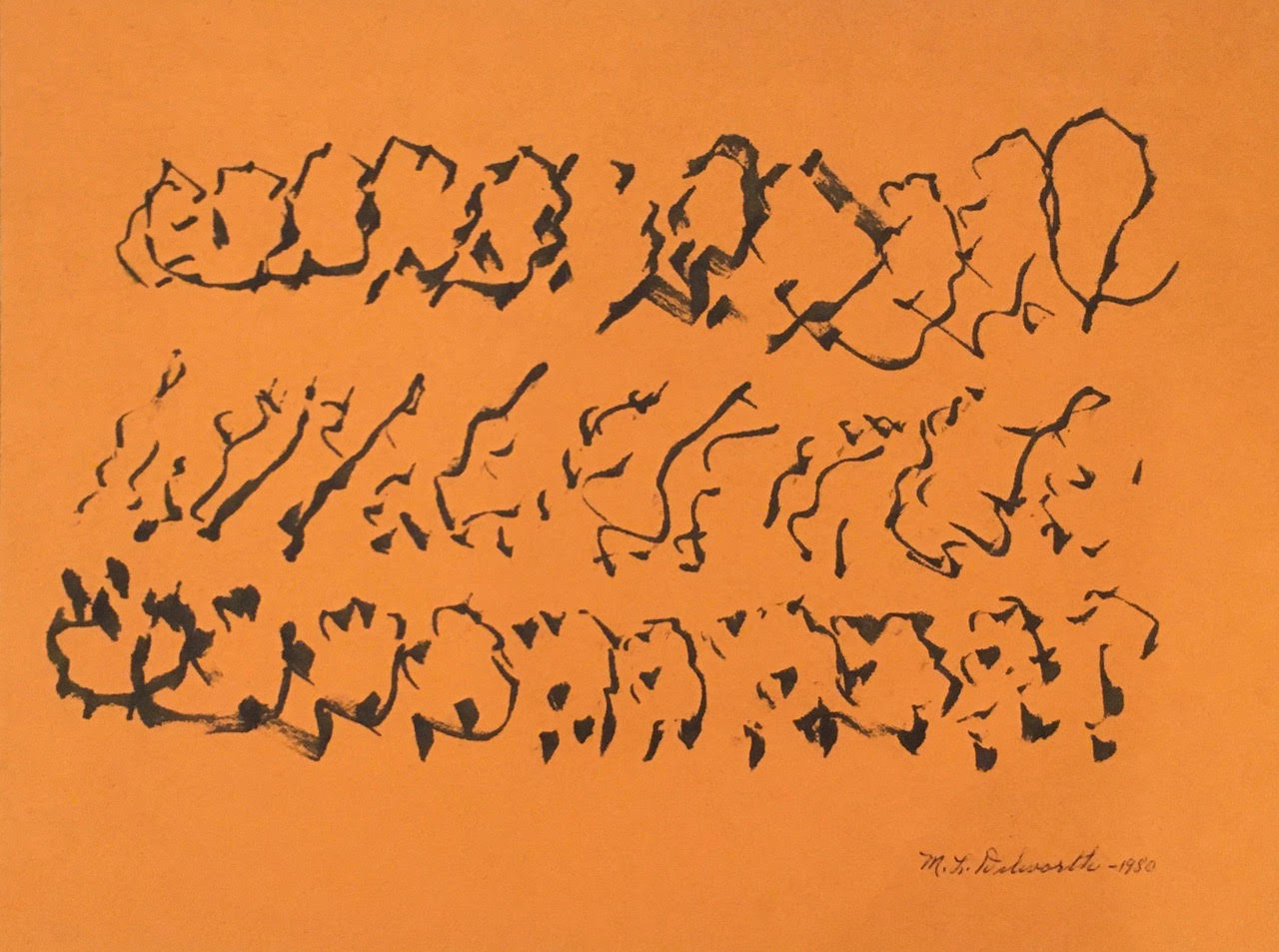

I likewise cling to my mother, Mary Louise Dilworth. Growing up we had original if not always great art on our walls. She was widely sometimes wildly creative. Alongside conventional oil painting she would do things she referred to as her Picassos. Oddball things, loopy and free. She glued palette scrapings onto wood. She poured enamel onto masonite making spectacular abstract events. Most striking were the drawings she made with Parkinson's. Allowing the tremor of her hand to track on paper in ink or watercolor. Visually stunning, they speak of life defiantly. They are the finest drawings I know. Raphael’s are great too.

Van Gogh’s the best painter to have lived. Too beyond to be influence, he conjured a universe bigger than the art world of his or any time. Rothko grows. Not many other influences have endured. Ryman was an influence for a while. His spare reflectiveness. I once had the privilege to see him in his studio on the lower west side. His studio was so big that he seemed small. More tinkerer than painter, Agnes Martin stole his thunder, proving to be more nuanced. Her neighbor told me stories about driving her in sun-roofed car for miles for days with her leaning back looking at the sky. That when stopped at a five-star hole-in-the-wall restaurant a guy at the next table noticing her casual clothes said to Malcolm: ‘Well she must think she’s someone important coming here dressed like that.’ Malcom explained that she was in fact a famous painter. Asked what kind of paintings she did, she told him: ‘I paint with my back to the world’

Marden was heroic to me, peaking at Dia with the Cold Mountain Paintings in 1996. At that time I handed his assistant my mother’s Parkinson’s drawings to show Marden. Sam returned them to me saying he showed them to Brice. I prefer to think he didn’t. As he had nothing more to say if he saw them, Marden must have been bothered by them as they presaged his own best work, though on a much smaller, therefore perhaps dismissible, but intimate scale. Having inhaled full breath of the Cold Mountain Paintings I have ever since gladly followed Marden’s work. But sadly instead of a lion roaming the land reveling in splendor, he seemed to evolve becoming a caged animal pacing. Once on 57th street, at a de Kooning show I was looking for a very long time before I realized the one other person looking all that time was Marden. After another 40 minutes I left to go to work. Marden was still there.

From the WSU days John Egner was big. John taught me about living as an artist. He also taught me how to play handball; the NYC, single wall, simple ball, off the street version. Thirty years ago we began in March playing at the courts on Thompson and Spring. We’d play seven games and he’d win them all. Early summer the teacher in him prevailed when he told me where to better position myself on the court. On Independence Day, I won all seven and rarely lost after that. I regret that for reasons not between us but around us, that friendship that I thought would be lifelong faded away. Looking back to the morning in Soho, walking by John’s home on Mercer when I, on the spur of the moment, rang his bell and went upstairs to find him and Robert Wilbert hanging out. And me then with them. Generations of artists from Detroit in New York, happy in each other’s company.

Fig. 8

The future of painting is where it has always been. Best on walls in homes. Not because I was a great carpenter but that I could be trusted to do handyman things around significant (expensive) artworks, I worked for some time for Sally Ganz. She and her husband collected Picassos from Picasso. Her home filled ceiling to floor with astonishing art. Easier to leave the walls than take things down to repaint. The paint on walls, peeling, pulled itself curling with affinity towards the art on the walls. It was glorious. Diminutive Sally, with a gravelly smoker’s voice, would insist I take breaks and served steamed pears while her cat walked the mantel rubbing against the painting Picasso got in trade from Matisse. Seeing some of the Ganz Picasso’s on museum walls years later, they looked more like pages in a book devoid of contextual living, parched by the side-by-side march of images.

Painting was, is, and will be an eye-to-eye thing. Words a distraction tossed in effort to substantiate the talker; painting’s power presides silently beckoning an equally powerful, silent, and fetching response. Is there anything else? Like High Peak Monocacy early in the pandemic shutdown, your offer to engage in whatever this conversation is has drawn me out, through my own world into the wider world. Thank you.

[JR] Thank you, Bill. I’m grateful to you to have this exchange, from Hamtramck to the Adirondacks, in quarantine. During this time, the world really changed in ways we could never have imagined. I was thinking, in an earlier part of our conversation, we were talking about your video, of the river, and I was asking about the character of a river, its flowing, moving, changing, life-bearingness, not yet aware that just a month or so later we would name our first kid River. It’s a really wild and flowing world of/in which we are part and parcel. We are not unlike rivers ourselves. Nancy Mitchnick told me the other day, the name River made her anxious, “because rivers flow away.” But I think that’s perspective; “away” moves away from a point of view. “Rivers flow,” I proposed, always arriving and always departing. Like conversation.

Jonathan Rajewski is an artist and writer who lives and works between Hamtramck, Michigan and New Haven, Connecticut.

Fig. 1, Walter De Maria, The New York Earth Room, 1977 © The Estate of Walter De Maria, photo by John Cliett courtesy Dia Art Foundation

Fig. 2, Bill Dilworth, Hit Drawing (@100 minutes), February 5, 1976, pencils on paper, 22 x 30 inches | photo by Andy Romer

Fig. 3, Bill Dilworth, Found Art (Woven Green), 1987, woven plastic on wood, 28 x 18 inches | photo by Andy Romer

Fig. 4, Bill Dilworth, (Untitled Blue Formica)1993, oil on Formica, 36 x 27 inches | photo by Andy Romer

Fig. 5, Bill Dilworth, Found Art (Shield), 1987, paint on and off wood, 30 x 20 inches | photo by Andy Romer

Fig. 6, Bill Dilworth, Untitled, 1998, oil on canvas, 15 x 11.5 inches | photo by Andy Romer

Fig. 7, Mary Louise Dilworth, Parkinson's Drawing, 1980, ink on paper, 9 x 12 inches

Fig. 8, Bill Dilworth, A Scent of the Amazon, 2016, oil on Formica, 72 x 48 inches | photo by Andy Romer

Read next: Black Lives Matter? by Fred Williams