She was not sure what she had to say about the writing of poetry. She had taught poetry for many years in a wide variety of institutions. And she had also read it alone, at night, isolated, for its pleasures in ways unrelated to the teaching. For years her relationship to poetry was almost a form of devotion, a devotion so intense that she would spend hours with its most extreme experimentalism, its most obscure words and writers. But then, heading to middle age, she mellowed and began to read wider and with more appreciation for the past, studying poetry’s lineages and its rhythms and rhymes. But now that she was perhaps in late middle age, perhaps the beginnings of elderly, she felt as if she could no longer understand how it had mattered. It had been such a shiny rock full of beautiful colors when she picked it up in the stream years ago but now, after years of sitting on her windowsill, the colors in the shiny rock had disappeared and the rock was just a rock and a dust covered one at that.

She was trying to explain how her rock had dried up to her friend who kept talking about literature and the ineffable or literature and the calling or literature and the transformative. She too wanted to understand the ineffable and the transformative; she too wanted to be called. So she tried to find something that mattered in poetry so she could explain it to her friend. She thought, what would I have most needed from poetry when I was in my twenties, living in a small town in the rural midwest? And in part the answer disappointed her. Because she knew that in her twenties she had seen poetry as a way out of the drunken nights partying in the fields with her friends. Poetry had been not a rock then but a big town. And she was determined to make it a town she lived in. But now, she thought of all the things she might tell someone who wanted to know something about poetry. She might tell that anaphora is underrated; how it is a tool of change, an invocation to that which is godly in us, a way of celebrating and calling and celebrating calling. And apostrophe, she might add, it is weird and foolish and yet what is a poem if not weird and foolish. It gets some work done for sure; it says you are reading a poem. She might say don’t write the self. Write about something you don’t know. It isn’t about you. Or it is about the you that is connected to all things, the you that is not recognizable in the word you. She might say do everything everyone says not to do. So then maybe do write about the self. Use foreign words. Neologisms are fine. It’s okay to not make sense. Feel free to use others’ words and forget attribution.

She thought she might tell the story of how she would come to poetry. She might tell her that the devotion would come through reading but the reading it would have to come through schooling because there was no way to know what to read otherwise and that was part of the problem. The rural town had given her detailed maps to get to the parties, but no maps to read poetry. And because it would be schooling that would be the gate, gender would be tied up in it. One day, years ago she found herself outside a professor’s office door, still wearing the outfit of the small midwestern town she had grown up in, hair still flipped back with a curling iron. She was looking at a list posted on the professor’s door, a list of those he was willing to admit to his poetry workshop. To this day it is unclear why she had submitted any work to this professor. Had she done it just because everyone else had done it? It now seems out of character. But anyway she had and her name was there on the list and the name of one of her classmates—messy dyed black hair that perhaps he had not combed for months, glasses dark and big, crew neck sweater that hung off his skinny frame, sexy too in his way— was not. And he said to her of course you got in, the professor only admits women. And only wasn’t the right word but mostly might work for he had said something that was mainly even if not entirely right. The professor she would come to learn was a weirdly aggressive libertine, the sort one had to say no to all the time. She would show up in his office and he would say of her lipstick “oh your lips look like they have been bruised after an afternoon of making love.” Or he would run his hand along her thigh and comment on the shortness of her skirt. And undeniably her skirt was short by then, because she wanted to live in the big town, the libertine town. The professor was a large man, with bushy eyebrows. An unattractive man. Later a woman in her class would live with him, eventually marry him. Now when she thought of him she thought of him as a poet who wrote about sex and menstruation and deep mystical practices.

But she would be able to use him also as a library. She believed that there are two types of sexism that women who want to learn things encounter in higher education. In one type they are cut out, discouraged, not taken seriously. In another they are harassed and yet offered an opportunity to get a reading list. There were more ways, of course. But that was how she would come to justify her study of poetry, showing up at the professor’s office, poems in hand, like he suggested each week. He would read her poems in his small, book-loaded, dusty office with a very small dingy window and he would say some things about her body and she might even write some things about her body as a sort of exchange and then after he read her poems he would give her a list of things to read and she would write it down and sometimes leave his office and go straight to the library. Lautréamont, Rimbaud. Ashbery. She would go get the books, read them. Go back to get another list. He would say Ginsberg, Blake, Whitman. The holy, the lamb, the everything. Pound. Zukofsky. Coolidge. Were they always men? In her memory they were always men. But no, that wasn’t entirely right. He said Stein once too. He had described Tender Buttons to her as a book about a woman looking around a room, a fair enough description. Probably said Niedecker to her. But not Bradstreet. He hated Bradstreet. Then sometimes he would send her to get the book of cave paintings, the one with the ibex frolicking and oh, she would think this is where the poem should be. Or he would send her to get the book of the shepherds who wrote poems on aspens. Or the poems written on the bunks in Angel Island. She loved the nights when the library was open all night and she could find the book of poems shepherds wrote on aspens. She loved mainly moving from its fluorescent lights out into the cool night and walking back to the dorm, thinking of one of the poem the shepherds wrote, the one about longing for the land of their birth. And when she would go get Rimbaud even while she would understand nothing of it, she could feel its proximity to the thing her friend called the ineffable. Years later she would come to know the ineffable that was in Rimbaud and it was in the moment where Rimbaud is repulsed by what he is so he disavows all his ties to nation and to heritage and to his race and then goes and gets high and then he realizes how that is what he wants to be, something high and disavowing and not of any one nation.

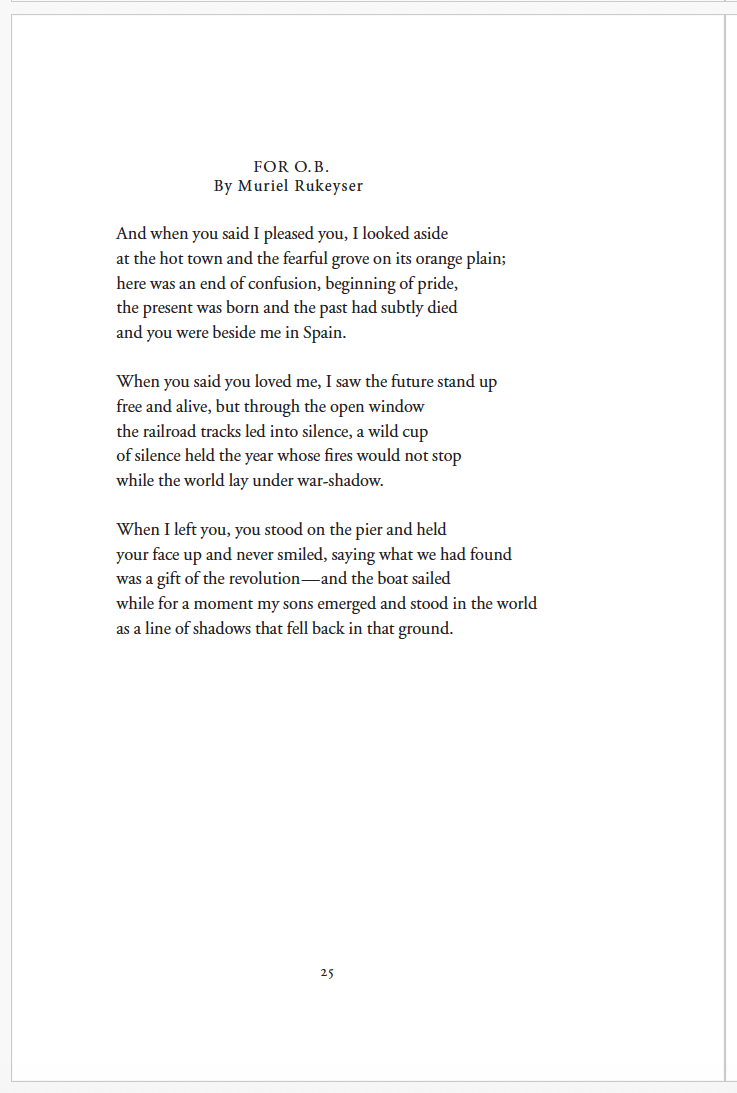

Oh these lists, how they indicated that poetry was a big town not a rock, a town she was determined to live in. And every so often, something opened up, something so exquisite she thought of a sort of lotus opening and inside its moisture was a small cup made of crystal that glittered and when she opened it she fell into it and suddenly there she was, her brain remade by the short three stanzas of a poem, like the one Muriel Rukeyser wrote for Otto Boch, the long distance runner, that she fell in love with during the Spanish Civil War. The first stanza with a hot town, an orange plain, and a hope. The second one about when someone says they love you and you feel it as a future, in a time when you are convinced there is no future, only a wild cup of silence. An orange plain and a wild cup of silence, those were some gifts. So much held in those two things. She did not know what a wild cup of silence might be but something in it worked. If she were forced to describe how it worked, she might say a wild cup is a place where a poem is held and when a poem is good, we will feel it in our chest, it is something bodily, next to the heart, whole, not broken and no one can take it away; it will not dry out. The wild cup of silence in her mind somehow held all the hopes that love might bring to someone, the juice of the orange as it were. The last stanza of this poem has the lovers separating and they say they have the gift of revolution but we know that the gift of revolution was not a gift that they could give as Franco took it, just as we know that the sons that Rukeyser mentions in the last line were not real sons and she could not give them to this world that held the never to be gifted revolution.

These were the thoughts she would have in this night with its cool air, thoughts about a poem that was an orange plain, deferred, moist, far away. An orange that one sees when one looks aside after someone has told you that you please them and one sees a hot town and an orange plain, off in the distance. The orange as holding all that is moist and sweet and she wanted to give this impossible thing that the poem could only see from a distance in a sideways look, that ineffable thing that holds oil in its skin.

Muriel Rukeyser, “Barcelona, 1936” & Selections from the Spanish Civil War Archives, Lost & Found: The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative, Series 2, Number 6, spring 2011.

Poet, scholar and editor, Juliana Spahr is the author of That Winter The Wolf Came (Commune Editions, 2015); Well Then There Now (Black Sparrow Press, 2011); This Connection of Everyone with Lungs (University of California Press, 2005); Fuck You—Aloha—I Love You (Wesleyan University Press, 2001); and Response (Sun & Moon Press, 1996), winner of the National Poetry Series Award. From 1993 to 2003, Spahr co-edited the arts journal Chain, which she co-founded with Jena Osman. Her latest publication is Ars Poeticas, Wesleyan UP, 2025.