Hear That Snap

Joel Peterson in Conversation with Hakim Jami

Bassist Hakim Jami is a musician whose career spans several eras of development in Black arts and culture. Like so many Detroit musicians, his accomplishments eclipse his acclaim, but he is held in high regard by his peers. From bebop to free jazz, he has worked and recorded with the masters. He’s been involved with artist movements that evolved out of Black self-determination in New York, Detroit, and Boston, running independent venues in each of those cities, as well as the label Reparation Records. He helped Detroiter Kenn Cox with the corporate formation of Strata, the legendary DIY record label, production company, and venue that Cox started after a battle with Blue Note over creative control related to his band The Contemporary Jazz Quintet.

I first got to know Hakim around 1999 or 2000 at Detroit Art Space, the venue he programmed in its early, golden era. Most weekends, Hakim led his group The Street Band, which featured a heavyweight line-up of Detroit creative musicians, including Faruq Z. Bey, Michael Carey, and Skeeter Shelton in the saxophone section; drummers Ajaramu Shelton, Howard Birdsong, and Ali Colding; and an assortment of occasional contributors, such as Tony Holland, Kenneth Green, Charles Hopkins and others. This was, to my knowledge, the last creative music ensemble to have a sustained weekly gig in Detroit.

Launching an independent venue was nothing new for Hakim. His East Village club Ladies Fort was part of New York’s legendary loft scene of the 1970s, within a few blocks of others run by saxophone colossus Sam Rivers and free jazz drummer Rashid Ali, both of whom he’s performed with. I recently sat down with Hakim, now 80, for a lengthy conversation about music, Detroit, New York, the remarkable lineage of Cass Technical High School—Detroit Public School’s magnate school for the arts—and his work with people like Sun Ra, Ted Daniels, Sonny Fortune, Roy Brooks, Archie Shepp, and Don Cherry.

–Joel Peterson, Three Fold Music Editor

I. Early Days

Three Fold [TF] What a strange time, with hardly any musicians working.

Hakim Jami [HJ] Nobody. Even the cats in New York ain’t working. I talked to Blood [guitarist James “Blood” Ulmer] yesterday. He was booked to come play at the Aretha Franklin Amphitheatre when this stuff started. He says he still wants to come to Detroit. I would like to do something on the internet. Otherwise, the clubs are not open. And people won’t wear their masks. What are you doing man?! Put the mask on! But they won’t vote for me, so what can I do? Ha!

[TF] Who missed that electoral opportunity? Navy veteran and all...

[HJ] Right. But you know I haven’t gotten anything from the armed forces. Nothing. I was in the service between the Korean and the Vietnamese wars. I went in there in 1957 and I got out in January of ’61. All these benefits they keep talking about for veterans, I don’t get none of that. I got out in January but they say the war started in April, and that GI Bill was only for the veterans that went in after April. I don’t know…I got what I wanted. I went to school there.

[TF] What did you study in naval school?

[HJ] Music. I went to naval school for a little over a year. Well, maybe a bit more, cuz I got high, you dig? I couldn’t pass the audition. My class had all gone to sea. I was the only one left. I was hoping they’d hold me a little while longer, but they finally took me to sea. There were two cats in the band that were really musicians. One played trombone and the other played trombone and vibraphone, Ronnie Pickett from Gary, Indiana. They were older than me and we did a cruise together to Denmark, Spain, and Scotland, and all the while they taught me. It was cool. But that was it. When we got back to the States, they split. I guess they had been at sea for a year or so before I got there.

[TF] Did you enter the navy right out of high school?

[HJ] I quit high school. I had been going to Cass through the eleventh grade but there were none of my cats—you know, I’m from 12th Street, right?—none of them were at Cass. So I said, shit, the last year I’m going to switch to my neighborhood high school. That was the worst mistake. I had already taken all the senior year subjects they had at Cass, so they put in some ninth-grade subjects. That lasted about a month, then I quit.

But the navy saved me, in a sense. I could’ve gone to any of the schools I wanted because my marks were high. They tried to get me to go into electronics as a technician, except I wouldn’t. Then they wanted me to do sonar. That would mean I would probably end up on a submarine. I said fuck that! So then they said well we’re gonna make you a radio man. I could tell the level of sonar, that beep, whether higher or lower. Finally, they decided to let me take the audition for music school. I got in as a drummer.

[TF] Really?

[HJ] I got in Cass as a drummer, but then they wouldn’t let me in the concert band, so I quit playing. I wouldn’t play the drums in the junior band. The only cat in the band that I had a rapport with was the tuba player, so I started playing tuba. For a year I was in concert band on tuba. In the navy, I did the same thing. I went in as a drummer, but I wanted to play bass. First they told me everybody has to play two instruments. When I told them I want to play drums and bass, they said you can’t do that. If you’re a drummer you just play drums; but if you play tuba, you can play the bass fiddle. So I said OK give me the tuba. I auditioned on tuba and euphonium. There were three bass players: me, Robert Friday, and Ron Carter. Doug Watkins had just got out the year before.

[TF] Cass Tech bass players!

[HJ] Yup. All of ’em. That guy that’s here now...his daddy used to work for the phone company...had a TV gig a few years ago?

[TF] Bob Hearst?

[HJ] Yeah, he’s a Cass Tech bass player too.

The interview is interrupted by Hakim’s phone ringing.

[HJ] It’s Blood. Hold on a minute.

Hakim answers his phone and has a short conversation with his collaborator James Blood Ulmer, probably best known as Ornette Coleman’s guitarist in the band Prime Time.

[TF] Did you know Blood when he lived here in Detroit?

[HJ] Not well. I met him when they had that joint up on Ferry Street. There was a place where they used to have jams. Him and Doug Hammond…I’m trying to think who else was in that group. Maybe in the late fifties or early sixties. I didn’t know Blood well until the sixties. I get up early in the morning. And I walk. In New York you can walk that time of morning. Five or six o’clock, people are out on the street, and the only one I knew that would be up and I’d run into was Blood. We started hanging out, getting our coffee, getting some barley soup and shit, you know. And it just grew. We had a few gigs together. But a lot of cats would get up like one or two o’clock. That’s when I’m going back to bed!

My father started me like that. He used to get me up to go with him and junk cars. When I was in high school, five o’clock I had to be hitting. He wouldn’t let me work for nobody. I couldn’t have a paper route. But I didn’t mind it because when I’d come home from school there’d be forty or fifty dollars on the table for me. If I had a paper route, that’d be all I would make in a week. But I’d make that in one morning, working with my pop.

Anyway, the dude that taught me when I was in the naval music school—I looked up one day and here’s Friday. We was in the Cass band together. He was a bass player, so I taught him the tuba and he taught me the bass. Oh, he was the phenom! He didn’t play with fingers, he played like that [holding his left hand in a tight claw].

Ha ha! But he could play! So I got out of the navy in January 1961 and he got out in March I think. I was stationed in Boston and he was stationed in New York. I went to go see him in December and he was flippin.’ I asked him what’s the matter with you man? He said, ‘Miles hired Ron Carter and that was supposed to be my gig!’ I told him, Bob, you’re still in the navy. He said ‘I’m gonna quit playing. I’m not gonna play no more.’ And I never saw him again. He came back to Detroit and was playing with some blues band when he died from cirrhosis of the liver, when you drink too much. But he was a good bass player. I mean that’s who Barry [Harris] used. He was the bass player on most gigs with Barry, Charles McPherson, Lonnie Hilyer…those were the young cats when we were in high school.

Yusef Lateef was the first one to hire Ron. I never did consider him, at that time, a jazz bass player. Yusef was the first to use him on a recording that I heard. And we said, ‘Damn, he plays jazz?’ Because he’s from Ferndale [although he attended Cass as a cellist]. He was like he is now. You know him? He’s not very jazzy. But anyhow, Friday said ‘I quit’ and he came back to Detroit and I never saw him, none of us. He grew up with Roy [Brooks] and like McPherson, Lonnie Hilyer, Hugh Lawson—that was the band when we was kids. Maybe one day we’ll all get together and have a Cass Tech bass players reunion. I don’t know where Jaribu [Shahid] went to school. He’s younger than we were.

[TF] He’s a Cass Tech guy.

[HJ] Probably, because if you had any aspirations musically at that time, I’m talking about the fifties, that was the only place you could go. I didn’t last two months at Central [High School]. They didn’t grade you on what you were doing; they graded you on how you acted—you a nice guy, you got a nice mouth—but if you’re like me, kinda loud...

[TF] Were you at Cass between Doug Watkins and Ron Carter, or is Ron older than you?

[HJ] Ron’s about two years older than me. The bass players of Detroit my age were Paul Chambers. Doug Watkins, and the next one was Bob Friday. Then Ron, then me, then Jaribu, and Bob Hearst. Somebody put out a book on jazz in Detroit—the ‘who’s who’ of Detroit jazz—but he has more rock and rollers in there than jazz. He didn’t have Betty Carter in there, Ali [Muhammed], he didn’t have me in there; but he had Ralph Armstrong in there. I ain’t never seen Ralph on no heavy jazz gig.

Among the famous Cass Tech bass players, one of Hakim’s distinctions was his use of the bow, a product of his classical instruction at naval school at a time when most music programs did not admit Black students. Bassist Jaribu Shahid says, “Hakim was the one who made a lot of cats get serious about using the bow. He influenced a lot of bass players that way.”

Hakim was also famous for the power of his pizzicato pluck. I once sat backstage with the Sun Ra Arkestra while Hakim performed with saxophonist Noah Howard. The bandmates in the Arkestra were merciless to their own bass player: ‘Hear that sound? That’s Hakim Jami! Hear that snap in his tone? How come you don’t have that snap? Why can’t you sound like Hakim? Why can’t you have a tone like that?!’

Hakim was last stationed by the navy in Boston, where he met saxophonist Sam Rivers and later opened his first venue, an afterhours club two blocks from a police station. According to him, he had been court-martialed for a series of events, including throwing a euphonium into the Atlantic and urinating on a navy drummer in the bunks because he would tap incessantly at all hours. “I was an asshole then,” he recalls. After staying on the Boston scene for a couple years, he made his way to New York.

[HJ] All those jazz lofts in New York in the late sixties and seventies were run by musicians. We paid the rent, we put in the shit, we financed it, we promoted it, we did such a helluva job in the seventies in New York. But they made all our rents so high that we had to give ‘em up. My place was big. I had two floors, so I had music presentation downstairs and my wife was a dancer so she had a dance studio, and my office was upstairs. And that shit was happening, you know?

We fucked with [festival impresario] George Wein. He came to New York and brought the same people that he had up in Newport. We said, man there’s three hundred of us who could work all over the world. We were kicking their ass. His concerts, the Newport Jazz Festival in New York, was three days: Friday, Saturday, Sunday. We put on a festival for 10 days. His festival was from like eleven, twelve o’clock in the afternoon until ten or eleven at night. Ours was 24-7 in all five boroughs. It was centered in Manhattan, but we had gigs going for ten days in Staten Island, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. And you know, we kicked his ass.

He came back the next year talkin’ about, ‘Well we want you guys this time,’ and we said no. I mean, we made too much. Why should we join in with him? He came into our turf and ignored us like we weren’t there.

He would call every day and be like, who’s in charge? It’s a co-op thing so we don’t have a leader, we told him. ‘We sit down with all our musicians and make agreements. The greater body decided we didn’t want to participate in your festival.’

Man, within a few years I think he got to the landlords. The only one who came out ahead was Rashid [Ali], because he had bought his building. But everyone who was renting? My rent went from about eight hundred to two thousand dollars a month. Everybody’s rent doubled. Sam Rivers and I were but one block away. I was Bond Street just off Broadway and he was on Bond Street right off Lafayette. His rent doubled.

[TF] That was Studio Rivbea, and your place was Ladies Fort?

[HJ] Ladies Fort, yeah, cuz Joe Lee Wilson, the singer, had named it. I bought the club from him, and he had called it Ladies Fort, for Billy Holliday. Anyway, my place, Sam’s place, Studio We—that was [James] DuBois’ place, he had a whole building, six flights, and he had paid sixty grand and they ‘lost the records.’ Called the police on mounted horses. I come by there one day and the police are lined up on horseback outside. I said, ‘DuBois!’ He said ‘Hey Hakim, they’re trying to throw me out but the only way they’re getting me out of here is over my dead body.’

I said, ‘Well boy, they got police lined all around the block to make sure they can do that, so you better get your shit and get out of here.’ And he did. Now he’s in an old folks’ home. James DuBois, the trumpet player. He was down with Juma. You know Juma Sultan? Well he was there with Dube. So they put DuBois out, they put me out, they put Sam out. There’s one more, Rashid. That was Ali’s Alley. He was right on the borderline with Little Italy. Gangsters had told him they wanted to put cigarette machines, the dryer machines, real concessions in. He said no so they came back with baseball bats and broke his jaw. Tore up the whole front of his club. And that’s his building. They told him he couldn’t have a club there. They took over the club for like 10 years.

Like many musicians in Detroit and New York that I’ve spoken with, Hakim sees the crushing of the loft scene in New York as a deliberate move by developers to pave the way for jazz artists more suitable to the dawning Reagan era.

[HJ] What they was preparing for then was Wynton Marsalis’ ass in the joint. Instead of putting Spike Lee’s daddy or Frank Foster or Sam Rivers or Joe Chambers, Roland Alexander—you know, all them big band writers—at the Lincoln Center, they go and put Wynton in there. Now, I’m not debating Wynton’s got some skills, but if they’re going to have a leader for the Lincoln Center, they should have got one of the masters; not someone aspiring to become a master.

[TF] Somebody with real artistry in their background. You could say Wynton is a proficient instrumentalist, but with minimal significant achievements.

[HJ] I couldn’t whistle two bars of one of his tunes. And that’s a shame for somebody that plays in that position, when you got musicians in that band that are qualified. I mean Bill Lee, Spike Lee’s Daddy, he’ll write some shit man. He used to write real shit. I’d be playing and the next thing I know I’d be trippin.’ I played tuba in this group he had. It was me, Kiane [Zawad] and Curtis Fuller. All Detroiters. Matter a fact, the first major record date I had was a Detroit lower brass thing with Kiane.

[TF] Euphonium or tuba?

[HJ] Euphonium

[TF] Who else was on that session?

[HJ] Billy Higgins, Beaver [Harris] I think, Jimmy Garrison, Roland Wilson…

[TF] Wow, a big group.

[HJ] Yeah all big names, about 30 pieces. And we did that in 1971. Right after the Attica riot.

[TF] You mean Archie Shepp’s Attica Blues.

[HJ] And then we did another one in France in the eighties and nineties, with mostly the same personnel.

[TF] Beaver Harris and —

[HJ] No, this was Clifford Jarvis. Shit, I can see their faces, but I can’t think of everyone’s name. Steve Toure...

[TF] So Attica was your first big session?

[HJ] Yeah, ‘big’ one. The first one was supposed to be a gig, and then the cat came up about six months later talking about, ‘Here’s the record.’ You know Ted Daniels, the trumpet player? He gave me the record but I don’t think I ever got no money for that. After that it was with Archie Shepp, doing the big band thing. I don’t know what the next one was. Might’ve been Hilton. I did two albums with Hilton Ruiz. Or, Roland Alexander and Kalaparusha [née Maurice McIntyre].

[TF] Any other recordings stand out to you in particular in the discography of Hakim Jami?

[HJ] Some I did with Kenny McIntyre, but what happened there was I turned down lots of recordings because I felt they should pay me more money and they wouldn’t. So I wouldn’t record. When Kenny McIntyre came to me to do this record with him and Beaver. He asked how much money I wanted. I was trying to be decent so I said give me five hundred. He said, ‘Hakim, he’s paying the whole band about five hundred.’ That was this record company that used to be in Denmark.

[TF] SteepleChase.

[HJ] I said let’s go into the studio, let’s rehearse our shit and we give him 43 minutes of music. We go in there, and told them to just turn on the machine and leave it on. We did it, it came out right, no mistakes, one take. And we start packing up, and he comes and says, ‘Don’t you want to do something —’ Nope! That’s it. That was the one with Kenny that sticks out. There are some good ones that haven’t been released that I did with Roland Alexander, Kiane, John Betsch.

[TF] You’re on one side of Don Cherry’s Brown Rice.

[HJ] Yup, I forgot about that one. I did one with Salim Washington, Strings.

II. Back in Detroit

Hakim has bounced back and forth between Detroit and New York the last few decades. He grew up on 12th and Claremont in Detroit, well-known as the epicenter of the 1967 Detroit Rebellion. “Those were my cats, the 12th Street Boys” he says, with a tinge of pride. His rough-and-ready attitude also translates to his pedagogical approach, although he has particular praise for the masters who’ve taught without bruising their students too hard, like Barry Harris and Marcus Belgrave. Our conversation turned towards what inevitably he sees as a decline in the creative scene and the loss of strong, experienced artists guiding the younger generation.

[HJ] That’s one reason I had wanted to organize some musicians, but I don’t know them. Like, I don’t know Ralph Armstrong or some of these younger cats. I tried at one time to get some rehearsals together. I didn’t get no response. Most of them want to play jazz. I can play bebop, but I don’t play no fuckin’ jazz. I’m trying to play what I’ve got to play and get us to some rehearsals. Band rehearsals. You know. Section rehearsals. Learn some music. I can’t understand why cats don’t want to rehearse. Hey man, when I used to play with Sun Ra, we used to practice all day and through the night. You know, I worked with a lot of cats. They rehearse. It ain’t no accident. These younger cats say ‘No we don’t have to rehearse, we’re free.’ Legitimately you’re saying you don’t know what freedom is. Because if you don’t rehearse you have no grounds to be calling yourself a free musician. They want everything to be by osmosis, I guess.

[TF] Sometimes that works, but it gets homogenous if that’s the only thing ever going on. Take someone like Sam Rivers: There’s a lot of freedom and exploration, but with prodigious control. His music also has real spirit and strong structural aspects and you hear every musical idea expressed clearly.

[HJ] Yeah, that’s the music! I’d been playing with Sam since Boston and he had some beautiful tunes. “Beatrice?” That’s almost a jazz standard. Cats play that tune. I like to play what they call ‘free’ too, but you got to have a basis, some kind of a platform you present, and then you go free.

[TF] In the Arkestra, Sunny always emphasized discipline.

[HJ] Discipline? He had a stack of music that high. Discipline?! Shit! We’d start practicing at eight in the morning and we would practice until three o’clock the next day in order to sound ‘free.’ It sounded like it was all freedom, but it wasn’t. You know, there’s certain rules of decorum when you’re on stage. See, I’ve played with some weirdos and crazy motherfuckers, but when you say ‘one, two, three, four’…they on the tune. And that’s the type of attention you have to have, or I do. That’s what I expect from musicians I work with.

I’ve been trying to get back to New York because the musicians here aren’t organized. I mean I can’t go to New York, stay for a year, and not get some rapport with at least 30 or 40 musicians. Here, the only musicians I hang with is Ali [Colding], and that’s it. Skeeter [Shelton], I was friends with his father, Ajaramu. I like Skeeter; I like how he plays. But there are certain things he doesn’t do.

[TF] That was one thing I loved about going to Detroit Art Space and seeing The Street Band. You guys were working together regularly so the ensemble was happening, and there was a shared repertoire of your own tunes and Faruq Z. Bey’s tunes and some of Skeeter’s tunes. You were playing all the time and it got real cohesive. But that kind of opportunity is now so rare here. Artists have to create it for themselves if they want to work frequently.

[HJ] It’s important that musicians create a cohesive plan. Like I said, we had four or five lofts in New York where we presented music. And we sat down and talked, like—‘Hey whatcha doing next week?’

‘I’m only going be open up Thursday through Saturday.’

‘OK, then I’m going to do a couple things on Monday and Tuesday...’

It’s got be strategic, working together. Even here in Detroit, there was a time when there was The World Stage, The West End, Jazz Center, or the place over on Tireman.

[TF] Blue Bird Inn.

[HJ] Yeah the Blue Bird. And 12th Street had Klein’s and a couple other spots. Everybody knew what was going on. You could synchronize, but I don’t see that really happening since Marcus Belgrave died. He was the beacon for a lot of activity. These cats don’t seem to be doing it. Everybody’s for ‘me.’ They never call so I’m going back to New York because the cats in New York call me. They treated Roy [Brooks] the same way, refusing to acknowledge he played with all those different people, that his recordings gave him a certain standing, and he had that standing wherever he went. These cats are still trying to reach a point where they feel like they’re professional. Most of ‘em ain’t professional. I would like to spend time with a lot of them, but they think I’m crazy. They do! They think I’m crazy!

[TF] There are more young players on the scene than the recent past, in their thirties and younger, and there’s some that are good and some that seem like they might have actual careers if they develop well, but what they all lack is access to real critique from significant players. I was thinking what a great role that would be for you here, workshopping and offering analysis.

[HJ] There used to be a club here called the Chit Chat on 12th and Virginia Park. And they used to have jam sessions. Well, I got out of penitentiary once and ran up to the Chit Chat because that was my neighborhood, and jumped up on the bandstand with Barry Harris, Richard William, the trumpet player, Roy [Brooks], Charles McPherson. And my chops were not up. I made one chorus of what they were playing, “Jeannine,” and I never will forget it. Roy jumps up from behind the drums and grabs the mic—

‘Will Austin! Will! Come get this motherfucker off the bandstand!’ [Hakim laughs] I couldn’t do nothing but grab the bass and go home and say to myself, well that shit will never happen again. And it didn’t.

Some cats, that drove them away. Not me. I went home and practiced. And those were my friends! You know, they wouldn’t tolerate that shit and they’d kick you in your ass. You come fuck up and then got an attitude? I’ve taken my euphonium and knocked the motherfucking drummer upside the head cuz he kept nodding out. So I knocked him out! And, you know, me and him were friends forever after that. But yeah, we would fight. You gonna mess up the music, we gonna fight. And that brought us up a level because you had to be on your Ps and Qs. You had to have your shit together or don’t get on the stand.

Young cats are not used to that. They be all ‘Yeah man, we sound good, man...’

‘You sound like shit,’ that’s the cats I’m used to. But the next thing you know, they call you, ‘Hey Hakim, come on and bring your bass by the house and lets practice that.’

What we should do as soon as the ease these COVID restrictions is get some of these younger cats. You know ’em, I don’t even know these cats. You know Esperanza [Spaulding], that bass player? I like her. Her and the drummer that played over at the Carr Center.

Charlie Mingus and Wilbur Ware both mentored me. Mingus had a lot of basses. And we were both working at the same club, The Bottom Line. I was with Sonny Fortune. One night when I came off the stage, I was sitting with my wife and mother-in-law and Mingus hollered way across the club, ‘Hey bass player!’ I said, aww shit! Cuz Mingus was known for poppin.’ If he didn’t like the way you played he’d take the bass from you! He said, ‘I like you. I like how you play, but you don’t sound like nobody I ever heard! Come on in the back.’

I went in the dressing room and he pull out his bass. He said, you like it? I said yeah. He says ‘Hey Booker,’ his manager’s name was Booker, ‘anytime Hakim want to play this bass, let him in the house to play it.’ So anytime I was down on the Lower East Side—I was living in Brooklyn then—I could stop by and play that bass.

Wilbur was mostly a good friend, but Wilbur could play. He played the bass. The best thing I could tell you is that it reminded me of an accordion. He could take time and open it up. And you’d think, he’s going to fuck up, he ain’t gonna get back in-time. And he always got back in-time. He was phenomenal, as far as his timing. Those cats would teach you. You know what I mean? It’s like, you gonna argue with Mingus? He’ll beat your ass! So those were the cats I hung out with. Because they said come with me and I’ll show you something. They would show you, as long as you didn’t argue. But I’ve also seen them be like ‘Don’t talk to me. Don’t talk to me.’ Especially Mingus. He didn’t like many people. But after we met, he and I became good friends. I mean, they were real people.

Up in Kingston, New York, they got this artist co-op up, Lace Mill. That’s where Juma lives. I’ve been on the waiting list since 2017. They called a few months ago and said you’re number two on the list. My daughter recommended I put in an application in three years ago.

[TF] I’ve been to Kingston and fell in love with it. There’s a lot of musicians up there…Joe McPhee, Michael Bisio, Tani Tabal...

[HJ] Tani’s up there?

[TF] Yeah, or at least very close by.

[HJ] See, I was so bad off a couple month ago where I was staying. I’m not there no more because bed bugs infested everything. I had to throw away all my clothes. I couldn’t have company. I couldn’t go to nobody’s place because I had bed bugs. It got so frustrating I moved. I just moved into my car. And my daughter found out about it and came here from New York and said you cannot live like this. And she stayed with me until I got situated again. You never know what life is. This child, her mother and I divorced when she was five years old. She’s 37 now and we hadn’t spent any time together, but she would not leave Detroit until I was settled. And it was good for me because I got to know her and she got to know me. Her mother never told her much about me. We bonded. And now we communicate. All of it was worth it to be able to relate to my daughter. Who knows what’s around the corner? I got so many grandkids! I got one boy with 13 kids!

Hakim’s new home is just up the street from my own venue, Trinosophes. As he disappears into Eastern Market, the nearby famers district where you could catch him busking for so many years, I’m left hoping that before he leaves, we can redeem our city in the eyes of this singular artist it produced.

Joel Peterson is a musician and composer. He is co-founder of the independent arts space Trinosophes, which publishes this journal.

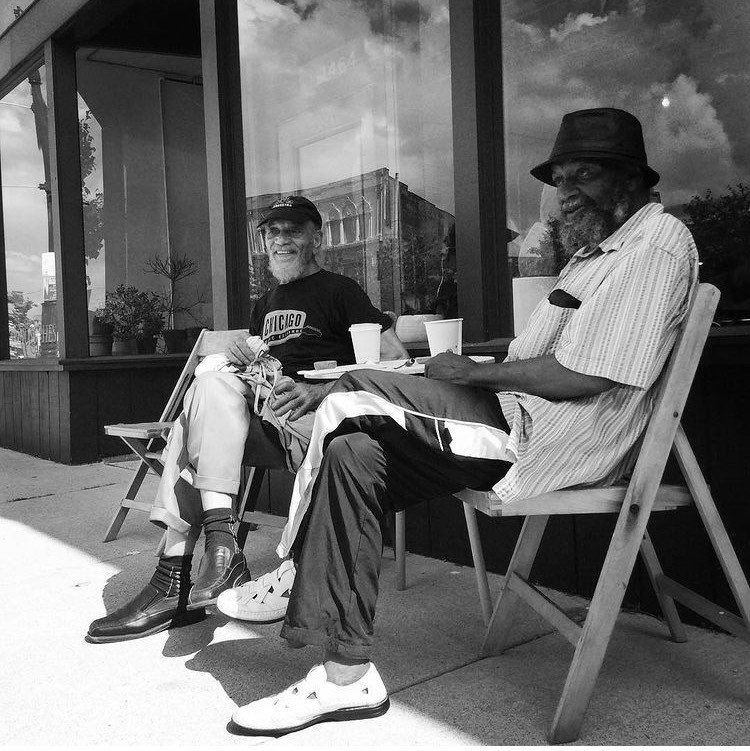

Lead image, Sun Ra Arkestra’s Marshall Allen (left) and Hakim Jami (right) outside Trinosophes in Detroit | photo by Rebecca Mazzei

Read next: The Orgasmic Space Poetry of Henry R. Lewis by Cary Loren