This is not an attempt to capture chaos

An introduction to the work of Sid Iandovka & Anya TsyrlinaBy Herb Shellenberger

I begin this piece unable to encapsulate the many hours of viewing and contemplation of this work, or of the conversation in several different countries with the people who made it: Sid Iandovka & Anya Tsyrlina. That’s because their films, their art and their way of thinking are so markedly different from what I’ve encountered in years of curating, writing, witnessing and thinking about art, that they require a different approach. Boundaries need to be redrawn; categories of data need to be reconfigured or done away with. Explanations don’t always fit things that are unruly and slippery, and sometimes the way things are usually done just doesn’t work. And that doesn’t need to be something shied away from or brushed under the carpet, but rather that can lead to affirmative, nourishing and even liberating encounters. This publication—As Yet Untitled: A Dossier on Sid Iandovka & Anya Tsyrlina—is not an attempt to capture chaos, but rather to illuminate a few elements, aspects and motivations of their films.

We can set some coordinates: Iandovka & Tysrlina are an artist-duo whose practice extends across many different media, predominantly moving images. Though only selected works of theirs are co-authored in a traditional sense, as both have distinct interests and aesthetics, they have collaborated (on and off) for almost thirty years—each being the other’s only audience—ultimately creating a joint, entirely independent, “homemade” production approach for their films. Their practice is not rooted in any state; it is immaterial and doesn’t benefit from any national/international funding, resources or structures. Similarly, their working methods are not products of any educational/professional institutions. Finally, the artists are cynical about any benefit that could come from their own personal biographies being spelled out in association with their work, and thus choose to limit this information.

The foundations of their work and sensibility can be traced back to the context of their formative years, when they met as teenagers playing experimental noise in their hometown in Siberia. They soon became—to borrow Genesis P-Orridge’s description of Psychic TV—a video-group-which-also-does-music, rather than a music-group-which-makes-music-videos. This music practice morphed into experiments with VJ’ing and new media, towards what they’ve now developed and refined over the intervening decades. Perhaps not coincidentally, their peculiar editing style, as well as their practice of trading work and collaborative edits, could be understood as an analog for how people might describe musicians co-improvising, i.e. as “jamming.” The same sense of punk’s DIY spirit is taken up in their practice of recording, manipulating, cutting together and fucking with moving images.

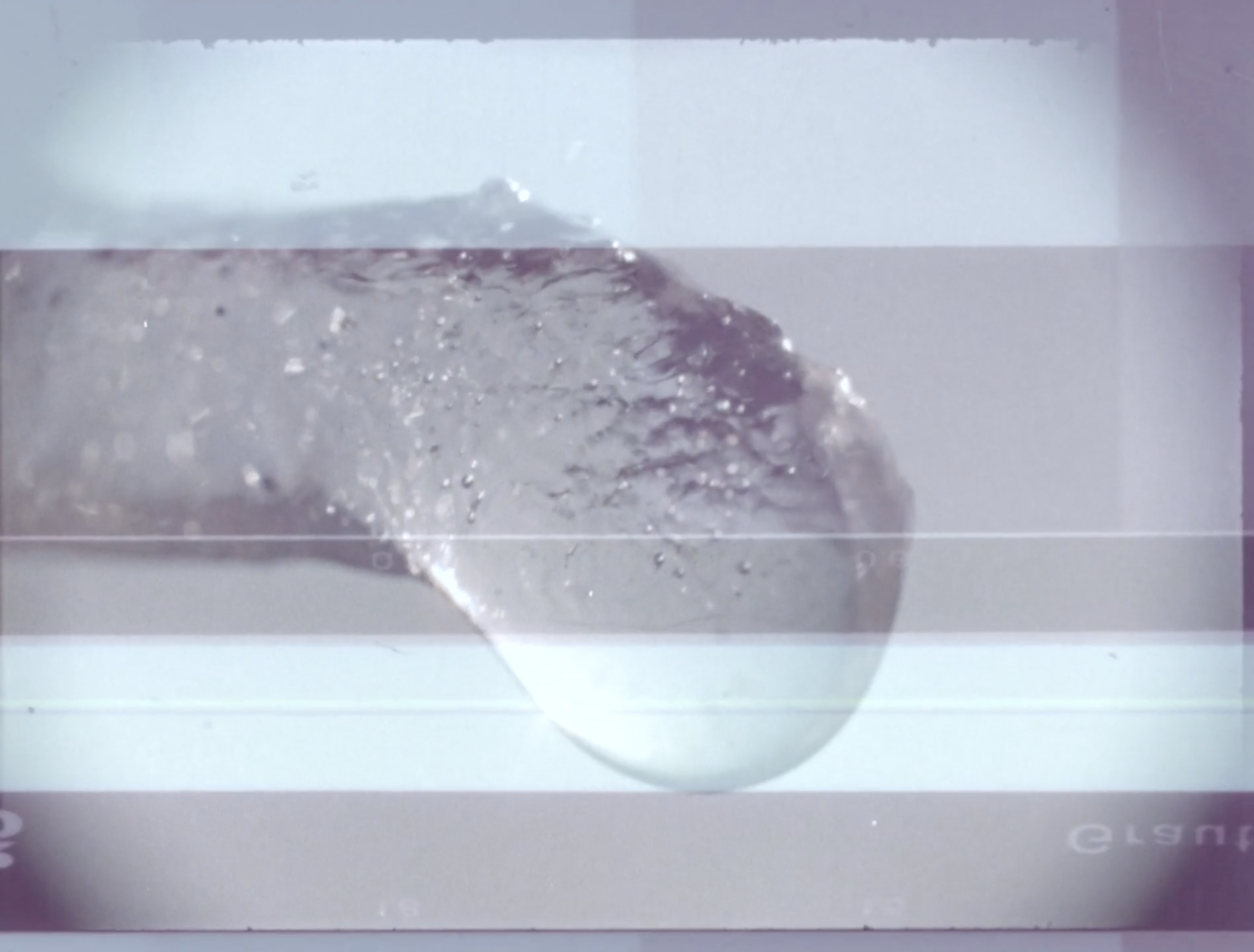

Zooming out yet again to speak generally about the duo’s process, we find a filmmaking technique that runs on intuition, with decisions often made on a level that can’t really be encapsulated by language. (Also there isn’t much language or dialogue in their films.) Sometimes films are the result of a quick and immediate creative burst, for instance 193 Octillion and Live the Life you LOVE were started and finished within a single day. More often, progress is made at a glacial pace, existing only as editing “timelines” and “sequences.” Projects might be incubating for years before being “done,” if there is ever a final version. They work on several “future films” in parallel over a prolonged period, as well as rework and remix completed pieces—layering previous intentions, personal story and history. For years, the duo did not have any finished work. Things were lost, deleted, obsolescent or corrupted, files always in a state of reformatting out-of-date codecs and so on. A box with video tapes was left somewhere and discarded, or else a hard drive stopped working. But these moments were not tragedies. Things move, change, develop and process in the way they should. Now they recover images and moments from earlier footage and works, which they develop into new films.

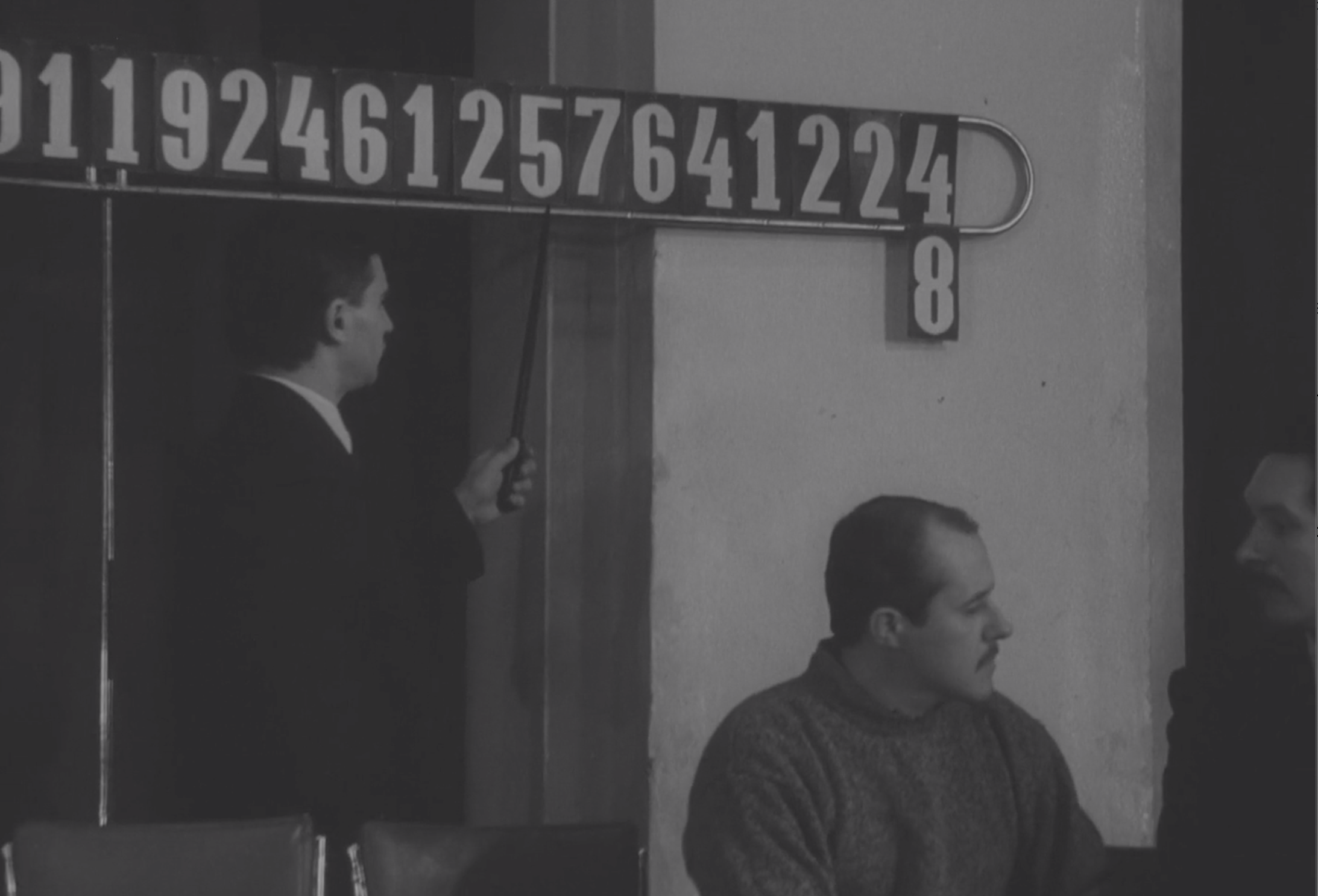

The vast majority of images they have used for their films are sourced from their own archive, mostly filmed by Iandovka and going back to the ’90s; for example, phenomenon (2018) is edited from their very first analog videotapes. Peter the Wolf features footage shot in Detroit during a spontaneous trip to check out the first Detroit Electronic Music Festival in 2000. It is also noteworthy that only recently, owing to Anya Tysrlina’s developing interest in documentary and to improved conditions of access, have they started using Soviet archives as a rich source of images (as in horizōn, 193 Octillion or All Other Things Equal). Iandovka’s early solitary experiments with desktop editing and lo-fi CGI, based on exploration of pirated software variously misused, hacked and only partially understood (“jamming” in a different sense!) can be traced to recent films stitched together from visual fragments undergoing varying levels of manipulation and continual reconstitution. These works incorporate complex animations (never obvious as such) into dense layers of visual trickery.

The two filmmakers are rarely in the same place; rather they often work many time zones apart, exchanging files and edits and “sharing screen.” Iandovka generally sculpts the sound from his own electronic compositions. But it’s not essential to know the whys and hows of these works, since there’s an almost alchemical and mystical quality to them that supersedes their construction. The filmmakers would prefer for their own actions and words to remain in the background and let the work speak on its own.

As a curator, it is a challenge to resist assimilating such an unruly practice into the ways in which I’ve previously analyzed, discussed and categorized films as art. And that’s partially why I’m so drawn to Iandovka & Tsyrlina’s work—and also why I find it important to highlight. These are two of the most self-effacing artists (and people) I’ve ever met in my life. Their humility is deeply engrained in a way that I almost find angering, because I want to shout about their films, which I’ve had beautiful experiences watching and interpreting. But through several years of conversation and patient exchange, I think we’ve finally gotten to a place of understanding where their work sits. It’s not a pickiness or prickliness with which some of my ideas and impulses have been rebuffed, but because the duo is so in tune with their own frequencies, with their past and present and future, that they know precisely how their work should best be elucidated. In some sense, this dossier and the accompanying exhibition have forced them to think through some things which previously may have been lingering or unclear.

In his brilliant exegesis on the work of Sid Iandovka & Anya Tsyrlina, published for the first time in this dossier, philosopher Thomas Zummer writes that the artists “let an image, whatever it might be, just be what it is…without being inscribed into a regime of sense that further violates or tethers it to a foreignness that is not its own.” When you have the opportunity to actually see the works of this duo, I hope you immediately recognize the importance of approaching any particular image as it is, rather than holding it within any existing frame of reference you might be familiar with. This is the best and most generous approach that viewers can give these artists’ work, and in return we will be rewarded with experiences that are stimulatingly unfamiliar and richly satisfying.

This dossier—which begins with the present introduction—continues with the aforementioned text by Thomas Zummer, a shortened edit from a longer piece, previously unpublished and included with his kind permission. It is followed by a selection of work: documentation of a VR installation in conjunction with the film phenomenon (titled Yet Untitled 1993–2017) and the recent film by Iandovka, a minor piece of damage, accompanied by related images. The dossier concludes with what might stand as a partial, fragmentary and deconstructed filmography, taking into account the gaps and exclusions detailed above. Also embedded throughout is music by Sid Iandovka, which will complement the perusal of each section.

This dossier is intended to accompany the forthcoming online exhibition for Media City Film Festival’s ThousandSuns Cinema: As Yet Untitled: Five Films by Sid Iandovka & Anya Tsyrlina. This is the first solo exhibition of multiple works by the artists, and as its curator I am grateful to Oona Mosna—Media City Film Festival’s Program Director and Three Fold Film Editor—for her support, as well as for highlighting in-depth the work of an artistic duo which has not been exhibited widely. My most sincere thanks also extend to Sid and Anya for sharing their work, and for endless conversation, generosity and criticality.

Herb Shellenberger is a film programmer, curator and writer based in London, originally from Pennsylvania. He is Programmer for Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival and Arts Programme Curator for Sheffield Doc/Fest (both in the UK). He is a chapter author for Dream Dance: The Art of Ed Emshwiller (Anthology Books, 2019) and Free to Love: The Cinema of the Sexual Revolution (International House Philadelphia, 2014).

Read next: (annotations on some works, possibly in progress) by Thomas Zummer