An excerpt from Ferne, A Detroit Story

By Barbara

Henning

An excerpt from Ferne, A Detroit Story

By Barbara

Henning

Introduction

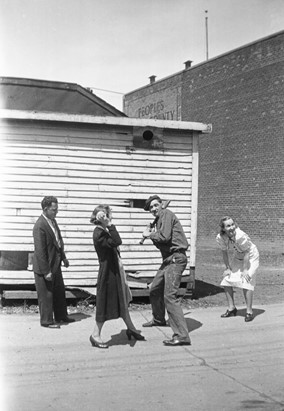

I began writing this story of my mother’s life when I was an undergraduate student at Wayne State University, as an assignment in a Women’s Studies class. My mother died when I was eleven and so I was happy to imagine her life and interview her sisters. Thirty-some years later, after my father died, I was given the Snaps photo books she had put together over her brief life (1921-1960); that’s when I started writing Ferne, a Detroit Story.

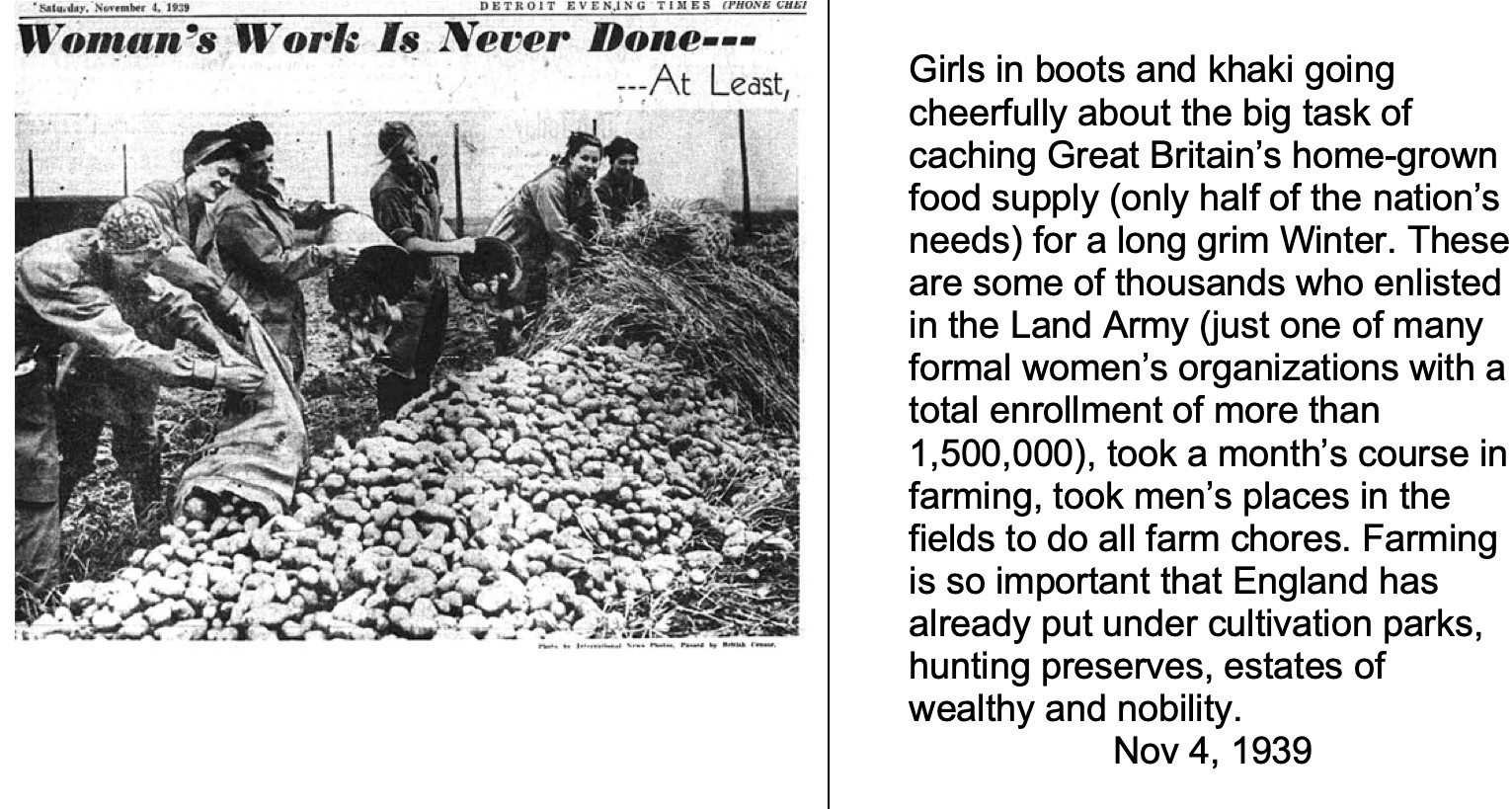

In order to understand her life, I wanted to also experience what the city and the country were like at the time. I didn’t want to read history books (but ultimately I read many). As I was going through the albums, I came upon a photograph Ferne had taken August 20, 1939, in the alley outside her house with the notation: “Times paper boys.” My grandparents had rented garage space to The Detroit Times. The boys would pick up their papers there and that’s where my father started his paper route. The Detroit Times was a working-class Hearst newspaper, and it was in existence for almost the same years that my mother was alive. Those coincidences helped me decide what to do; I spent many weeks in the microfilm rooms at Detroit Public Library and in the Lansing State Archives, searching on dates that were important in her life, looking for news articles of interest to working-class women and families. Occasionally, I would also go to the digital files of the Detroit Free Press. Finally, I wove the photographs and clippings together with the story and memories.

I wrote my mother’s story because I was in love with her and I wanted to know her as “Ferne,” a woman who had lived in a transformative time, born when women first got the vote, a child during Prohibition and the Great Depression, then coming into her young adult life as World War II changed everything. I constructed this novelized (mostly imagined) biography-memoir based on stories people had told me over the years and memories I had of my mother during those first eleven years of my life.

Chapter 5

Jeane and Ferne were walking east on Jefferson Avenue. They had just left the Cinderella Theater.

“It’s really chilly tonight,” Ferne said, pulling her coat around her. “Seems like winter’s coming early this year.”

Jeane put her arm into Ferne’s. “It was really scary when Ida Lupino was caught in the brambles with all that fog and that guy stalking her, wasn’t it?”

“She’s beautiful with her tiny waist and her shoulder pads. They make her waist seem even smaller. I could make a jacket with shoulder pads like those.”

When they walked past the sweet shop where Jeane worked, she pointed to a sign in the window. “They’re looking for someone else to work in the evenings. I’m trying to get Margaret to apply, but her father won’t let her work evenings.”

When they turned onto Marlborough Street, a damp wind from the river blew a clutter of leaves off the trees, adding to the piles already crunching underfoot.

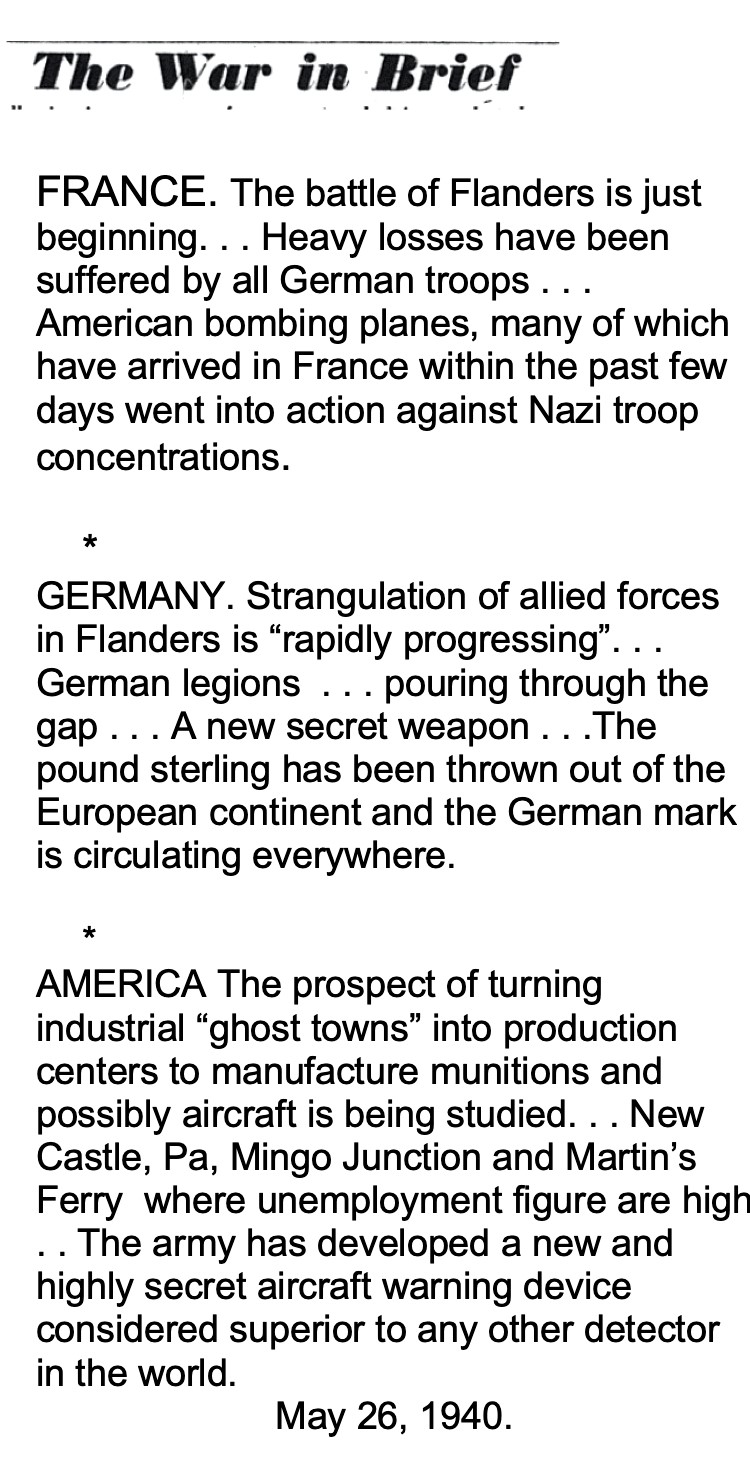

Ferne put her arm around Jeane. “The newsreel was horrifying, the German soldiers just marching into Poland and taking over, bombing buildings, blowing up their bridges. I’m worried. Maybe they’ll come here. Ma is scared the U.S. will get involved. Lynn and Ward were talking in the kitchen. They’re worried they’ll be drafted.”

“How’s Ma?”

“She started crying when I told her I was going to stay with you, that I didn’t want you to be alone. You’re too young. She told me she was going to call the police to bring us home.”

They turned in front of a two-story bungalow and walked along the side to the back door. They climbed up the steps to a small apartment with torn wallpaper and peeling paint on the ceiling.

Ferne looked around at the old furniture. “This place is a mess.”

“It’s the only place anyone would rent to me.”

“Jeane, Dad’s having trouble breathing. He’s walking very slowly. They want us to come home.”

“I thought I’d like it here, but all week I’ve been crying. Even though Margaret comes over, it’s just too quiet and lonely. I’m used to being around people.”

“Let’s go back home tomorrow morning. Everyone will be happy to see you. Pa wants you home, too. We go home tomorrow, right? I’ll take the day off work. Come on.”

“Okay.”

Ferne sat down on the couch next to Jeane. “There’s something I didn’t tell you.”

Jeane looked at her, “What now?”

“I got another letter from George. He left home and moved to Florida where his aunt lives, and he said he’s not going to college. His father is furious. I would’ve gone with him—he wanted me to—but I don’t want to disobey Pa. So now George is going to marry some girl from there.”

“What? Why is he in such a hurry? I’d like to tell him a thing or two.”

“The draft. They’re worried about the draft. If you’re married, you might not have to go.”

“What are we gonna do?”

Ferne stood up. “I know what I’m gonna do. I’m gonna go to the Vanity Ballroom night after night until I meet the right boy. That’s what I’m gonna do.” Then she turned on the radio. The Ink Spots were singing,

If I didn’t care, would it be the same?

And then they stopped singing, and one of the men said in a very deep voice,

If I didn’t care, honey child, more than words can say,

If I didn’t care, would I feel this way?

Would my every prayer begin and end with just your name?

“Are you okay, Fernie?” Jeane knocked on the bathroom door.

Ferne was putting her hair into pin curls. She looked into the mirror and Jeane looked over her shoulder. “I was in love with George, Jeanie, but I’m certainly not going to wallow in it.”

“Are you sure?” he asked. “I’ll pay the tuition to send you to beauty school, but you have to promise to finish.”

“I definitely will, Pa, definitely.”

“And Jeane, if you finish, maybe I can help you get started.”

Jeane enrolled and went to school for a little over a month. But she didn’t like washing other people’s hair, the endless rolling and pinning. She didn’t have the personality of someone who could endlessly attend to others. And they said she had to wear a white suit and wear her hair the same as the others. That really bothered her. Who wants to look like everyone else? So she quit going. Pa was more angry at her than he had ever been. She was throwing away his hard-earned money. When he hollered at her, she packed a suitcase and stomped out. Then yesterday Ferne left too, so she could look after her. He was bereft. Suddenly his last two children were gone and the flat was empty.

When he looked out the window and saw the two girls walking up the steps of the house with their suitcases: what a relief. “Hattie, they’re here,” he said, raising his voice a little and pretending he wasn’t ecstatic.

“I’m sorry, Pa,” Jeane said, looking to the side. “I’m not that good as a stylist. You should have seen how they laughed at me.”

He sighed.

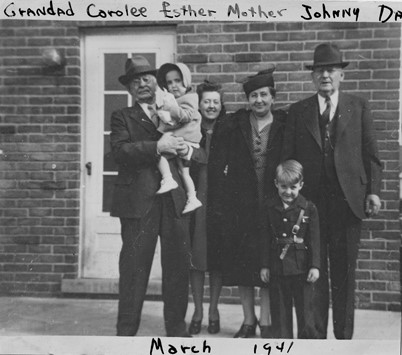

“Put your things away, girls,” Hattie said, “and have lunch with us. Grandad’s moving in this afternoon. I need some help setting up the sunroom for him. I also have laundry to do for Mr. Munjall. Ferne, can you help me in the basement? My shoulder is sore. You can feed the clothes into the wringer and help hang them.”

“Sure thing, Ma. I thought Munjall was going home to India. Didn’t he lose his dishwashing job?” Ferne asked.

“Apparently he begged Louie. For the time being he’ll have his job. Thank the Lord. He says he’ll be here until fall and then he’ll go home. Then Grandad will have that room.”

Katie came in the back door with her children. “Happy Mother’s Day, Gramma Hattie,” Dickie yelled jumping up to hug her, handing her a bunch of daisies.

When the family was sitting at the table, waiting for Luke to say grace, John looked straight at Katie, staring. “How’d you get that bruise on your face, Kate?”

“I slipped and fell down the stairs,” she said, her eyes welling with tears. “Such a stupid thing wearing those slippers.”

John stood up and turned around. “You’re bruised all over. Where’s Evan? Where’s that shithead? What the hell’s wrong with him?”

“He couldn’t come. He’s busy with some work he brought home and then visiting his mother. I told you, John, I fell down the stairs. He didn’t have anything to do with it.”

Everyone was quiet.

Luke Sr. stood up from the table. His voice was weaker than usual. “Listen, let’s not talk about this now. The children are here. We are celebrating our mothers today. Fernie move over. I want Katie to sit beside me.” He put his arm around her.

He cleared his throat. “Before we eat, I want to thank everyone for coming to honor Ma today. We’re sorry to have lost Pat. He was a good dog, but that fight last week with the Airedale was his end. We made a little grave for him behind the garage. Let’s say thanks now to God for granting us our health, love for each other and the food on this table. Please God protect us and protect our country in this difficult time. Amen.” A chorus of amens and then everyone started eating dinner and chatting.

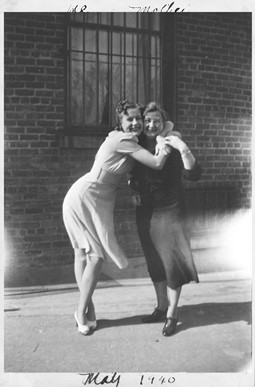

After dinner, Ferne hollered through the back screen, “Ma, come outside and take that apron off. Jeane’s gonna take your photo with me, and I’ll take hers with you.”

Jeane directed them to stand in the back of the bank. Ferne put her arms around her mother and Hattie reached up to hold her too. Cheek to cheek. Hattie was dressed for Sunday, wearing dark clothes, black shoes and her wire-rimmed glasses. She took one step forward, as Ferne’s hips flew out and about, her skirt catching the wind, her ankles crossed. It was high heel Sunday. Click and click again. Ferne and Jeane were in love with their mother. Behind them were the bars on the windows of the bank.

Later in the afternoon, there was a lot of racket going on in the back bedroom.

“John,” Hattie said, “would you take the children outside for a while? I want to talk to Katie.”

When John opened the door to the bedroom, he found Dickie watching while Barbara, Johnnie and little Carol Lee were jumping on the bed. “Hey! That was my bed when I was a kid! If Gramma catches you children doing this, you’ll be in a lot of trouble. Come on outside all of you. I’m going to teach you how to make a city of people from those hollyhocks.” They trailed out behind him as if following Johnny Appleseed.

Ferne smiled as she watched them marching toward the cinderblock seats behind the garage. She remembered John putting on hand shadow shows for her and Jeane when they were small and he was a teenager. She sat down at the kitchen table and poured a cup of coffee. She could hear Katie and Ma talking.

“We are working it out,” she heard Katie say. “It was my fault, really, Ma. You know how moody he is. I was frustrated after being with the children alone for too long and I nagged at him. I saw the lawyer, but we don’t need another divorce in the family right now. And I have the children. I don’t want to leave Evan. What would happen to the children?”

“Dear, you cannot let him push you or hit you. That’s unacceptable. Perhaps he only meant a little push, but the fact is you fell down the stairs. And you could have been seriously injured. Maybe you should stay here for a few days and let him think about it.”

“I need to go home, but if you and the girls wouldn’t mind, I’d like to leave the children here for a few days.”

Katie sat down beside Ferne on the front porch. “You don’t mind, do you, Fernie, helping Ma with the children.”

No, Katie. I wish you would stay with us too.”

“I’ve got to straighten this out. Everything will be all right. I just have to talk to him. You know, Fernie, it’s different once you’re married to someone.”

When she left, Ferne watched her walking down Alter Road toward Harper. Her striped dress got smaller and smaller until she turned the corner, heading west.

After going out dancing two or three times a week for a few months, Ferne told her mother she was going to volunteer for the army. Hattie begged her to reconsider. Ferne went down to the recruiting office in Grosse Pointe, but after the doctor examined her, he declared that she could not join the WACs because she had an irregular heartbeat.

She was very upset. “I’m completely healthy,” she said. “What can I do?”

Do you type? File?”

“Yes.”

“We need someone here. If things continue as they are in Europe, we’ll soon be flooded with work.”

She took the job and on Monday she started working as a receptionist. The pay was low but she liked Loretta, the young woman she was working with. They would chat all day long, and sometimes they went out together at night to dance at the Vanity or at Eastwood Gardens. Loretta lived with her mother and her brother. Their father had died ten years earlier in a car accident. Like many other families during the Depression, the children had to leave school after sixth grade and find work to help their mother.

Sometimes her brother Rob would come along when they went out dancing. He was almost six and a half feet tall, a hefty young man, two years older than Ferne. She taught him how to jitterbug and, even though he was a bit awkward, he could pick her up and swing her around the dance floor. After that, most nights they were together sitting on the porch at the Hostetter house planning for their future. After dark, they would walk around the block and then cut through the alley to sit behind the garage where no one could see them. Rob kept saying he wanted to marry her, but Ferne wasn’t sure. She liked him, but not as much as she had liked George.

“If we were married, we wouldn’t have to hide like this, Ferne,” he said as he stroked her hair. “I could bring you home with me.”

“Oh, your mother would really like that.”

“She would love it if I were married. She keeps telling me to get married. Loretta’s getting married and moving out soon. There’ll be more room in the flat for us.”

“Maybe, but maybe not. I want to have our own place. Couldn’t we rent our own apartment? We both have jobs,” she said standing up and straightening her skirt. He slipped his hand under her skirt and stroked her inner leg.

“Stop it,” she said, laughing.

“After a while, of course, we can save money.”

As the weeks passed, they started talking about having children.

When her father got an inkling of their intent, he was concerned. Not only was it too soon after George, but he and Hattie both thought this young man was too big for Ferne. When Luke spoke to Ferne, she cried and begged him to say yes. He hated it when she cried like that. Against his better judgment, he gave in, but he made them promise to wait at least six months before they married. He posted an announcement in the Detroit Free Press about their engagement and also Lynn’s engagement to his girlfriend, Helen.

On the morning of September 14th, 1940, Ferne and Rob were married at Knox Presbyterian Church. That evening, Ferne moved in with Rob and his mother in their flat on St. Jean Avenue. Loretta was still there, but only for a few weeks. After a week and a half, Ferne started coming home to her mother and father’s house after work, hanging around with Jeane and her mother.

“What’s going on, Ferne?” Hattie asked.

“Oh nothing, Ma. I just miss home.”

“You’re married now. You must live with your husband.” Hattie put her arm around her and kissed her. “You must go home and help with dinner.”

Ferne picked up her purse and her coat and slowly walked up to the corner for the Mack Avenue bus.

Three months after the wedding, Ferne showed up at her parents’ house in the morning with a suitcase. She didn’t like Rob’s mother, she said, and she was depressed living there. Gerty was nothing like Ma. She nagged continually, wanting Ferne to do all the housework after she came home from working all day. And she and Rob couldn’t get enough money together to have their own place, even with his salary at Chrysler and hers. And he never wanted to go out dancing or have fun. Ferne was adamant—if they couldn’t get their own place, they needed to live with her parents. But he wouldn’t leave his mother.

“You’ve only been with him a few months, Fernie. Married love isn’t supposed to be that easy,” Jeane said.

“Who said this marriage was about love?” Ferne turned on her side, sobbing. “It was torture living there. He didn’t love me, not the way I love. It was more about his mother. She didn’t want him to lose his job and go into the army. Pa was right, it was too soon. I wanted George. I feel smothered by Rob and unappreciated by his mother. And, Jeane, sex is not all it’s been built up to be. That’s all I’ll say about that.”

The next morning Ferne was throwing up in the bathroom with terrible cramps and a few drops of blood. Hattie asked, “Did you skip a period?”

“Yes, I’m two weeks late,” she said, weeping and moaning.

John drove them to the emergency room. Finally, a doctor told Hattie and Jeane that they were taking her into surgery. He thought it was a tubal pregnancy.

When Hattie was young, many women had died from tubal pregnancies, including one of her friends. A few hours later, the nurse told Jeane and Hattie that Ferne was fine. They had to remove one of her fallopian tubes and a blood clot, but the operation was successful. “She should wake up in an hour or so.”

When Ferne woke up, Jeane was sitting beside her holding her hand.

“Oh Jeane, why does everything go wrong for me?”

“Fernie, the doctor said the operation was successful.”

“I probably won’t ever have children,” she said weeping.

“That’s only a chance, Fernie. Remember that. It could happen to any of us. Try not to focus on the negative.”

“Where’s Ma?”

“She had to go home to take care of Pa. She’ll be back in the morning. Katie’s coming soon, and then I’m going home for a while.”

When Ferne came home, Rob stopped by to see how she was and to try to talk her into returning. “We’ll have a big family and I’ll look after you.”

Again, she explained to him that she had made a mistake. When she refused to go back with him, he turned around and never returned.

Luke thought she could get an annulment, but he insisted that she wait three months just to be sure she had made the right decision. When she explained to the judge that they had lived together for only a few months, he wondered why she hadn’t come directly to the court.

“My father made me wait,” she said. When she explained that Rob had promised they would get their own apartment, the judge would not entertain this argument. This was not a good reason, he said, to undo marriage vows. She could have lied and said that he was cruel to her or abusive, but she couldn’t do it, so Ferne would now have to work and save money to pay for a lawyer.

She took her wedding portrait out of the envelope and stared at it. She was wearing a dark dress with a white lace lapel and little white buttons down to the waist. Her hands were crossed one over the other, a wedding band on her left hand. She wore a large dark hat with some feathers and her hair was rolled in the fashion of the time. When the lights flashed, Rob was standing beside her. She took her scissors and clipped around the edges, leaving only a foot, a lower leg and one shoulder. The three Hostetter sisters and sisters-in-law also did exactly as Ferne had requested and clipped him out of all the photos. “Out of your life, out of the picture,” Jeane said as she clipped him out of hers.

In November, Ferne was in the post office waiting in line when she saw Rob up ahead. He was wearing a U.S. Air Force uniform. He must have enlisted, she thought. She tried to say hello to him, but he looked in the other direction. As he was walking past her, she said “I’m sorry, Rob,” but he walked straight out the door.

When she filed on April 26, 1941, the only way she could obtain the divorce was to claim cruelty and non-support. Rob did not contest.

A native Detroiter who lives in New York, Barbara Henning is the author of four novels and eight collections of poetry, most recently, Digigram (United Artists Books 2020) and a novel, Just Like That (Spuyten Duyvil, 2016). She has edited The Selected Prose of Bobbie Louise Hawkins (BlazeVox, 2012) and Looking Up Harryette Mullen (Belladonna, 2011).

Read next: An excerpt from About Ed by Robert Glück