End of a Life Sentence: 28 Years, 8 Months, 3 Days, and a Wake-Up

Six Reflections on Coming Home

By James D. Fuson

This text is part one of a two-part diaristic essay by James D. Fuson, who was a juvenile sentenced to mandatory life without parole in 1996. His sentence and the sentences of thousands of juvenile lifers would be later ruled unconstitutional by the United States Supreme Court. He will return home on September 27, 2022 after nearly 29 years confined by the Michigan Department of Corrections. “End of a Life Sentence” has been written by Fuson during the final months of his incarceration. He will write about his first few months after release for our January 2023 issue.

on the horizon

the sun

no longer sets

1. The Wait

It all starts at arrest. I wait in holding tanks and cells before moving to other holding tanks and cells. I have to wait for court hearings. I have to wait for lawyer visits. And once I got to prison, waiting became an art. I could pass the time by what I was waiting on: store, barbershop, a catalog order, an appeal, a counselor to come in, something to eat, laundry, the next shift of guards, what was coming on TV. That is life in prison. Just waiting and waiting. After 28 and a half years of hurrying up to wait, I’ve never in my life been so happy to wait.

When we heard the United States Supreme Court was to decide the issue of juvenile lifers back in 2011, we still had to wait for the court’s term to begin and end. The court decided in our favor in 2012, but because of the resistance to criminal justice reform in Michigan, it would be ten years before I would step foot back in court for resentencing.

After resentencing, it would be another year before I could see the parole board. A month after seeing the board, they deferred their decision until I had a psychological evaluation. This was because I had been locked up for so long—since I was a kid. That took another two weeks, and then the parole board finally came with their decision a month after that. They granted me freedom.

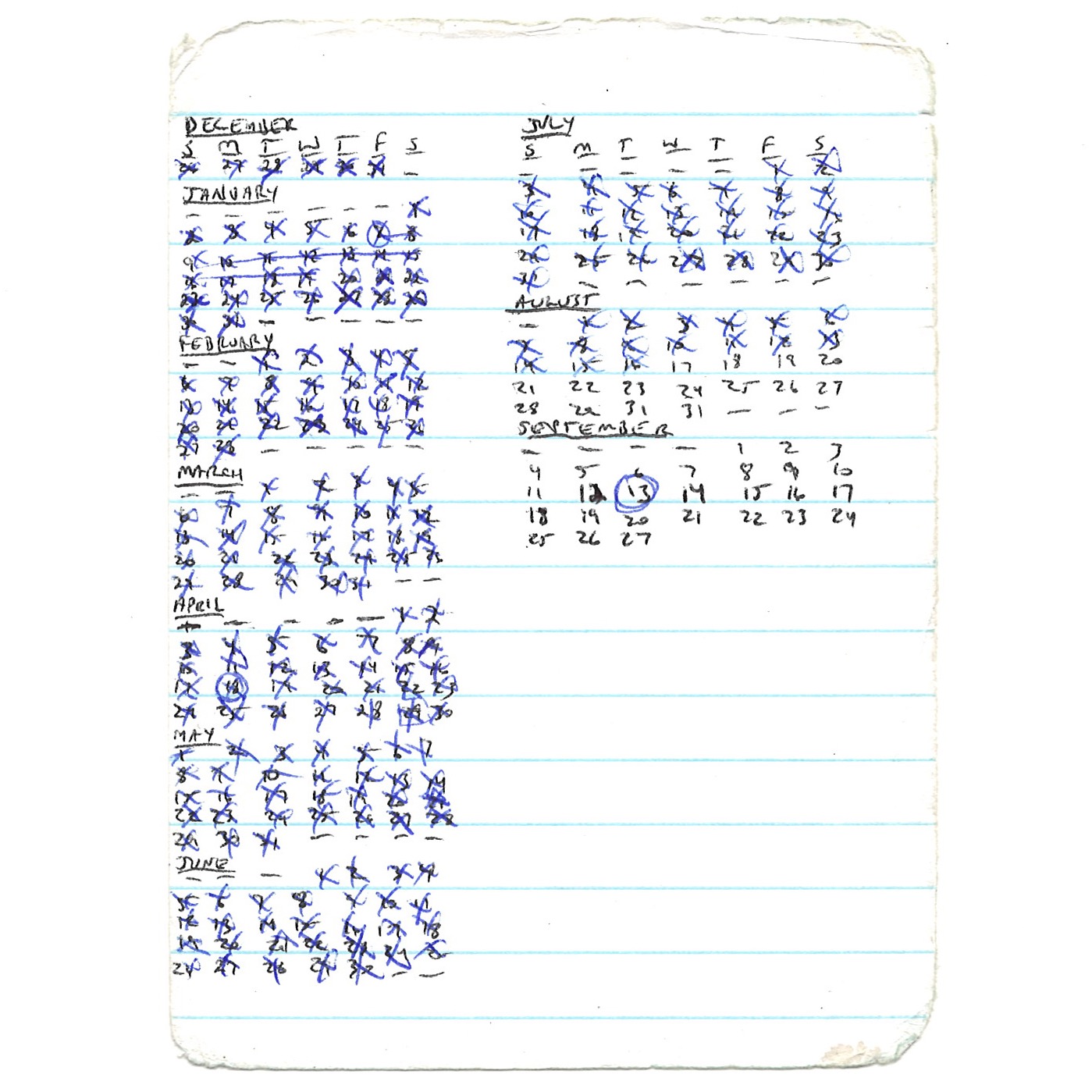

But the waiting wasn’t over. After I was resentenced, the Michigan Department of Corrections (DOC) central office calculated my earliest release date (ERD) as August 8, 2022, after applying over 27 years worth of credit for good behavior (called “disciplinary credits”). Then the DOC did a time review by subtracting days lost for bad behavior. My new ERD was now September 13 of the same year. And because bureaucracy loves paperwork, they did yet another time review, giving me another 28 days off my sentence. My new ERD should have read August 16, but it was still September 13. When I asked my prison counselor (a misnomer), he looked up my ERD and it read August 3. Confused yet? As I write this, I have no idea if I have 77 days, 49 days, or 36 days left in prison. I’ve even kept a handwritten calendar. But what once was a burden, a test of patience, is now the best problem I’ve ever had. I’m going to be released. Out there. I’ll breathe air that is not filtered through the concertina wire and chain link fence. I’ll be free of random and casual violations of my body and property. I’ll walk a path that is not laid out before me in yellow lines spray-painted on the ground. I’ll choose my own breakfast, lunch, and dinner. I’ll choose when I eat it. I’ll look up and see the moon and stars in the night sky. I will be free.

But waiting has consequences. For the people waiting on me, my family and my friends, those who are giving me a place to live, clothes to wear, food to eat, who will help me land on my feet and stand on my own. Waiting to celebrate my reentry into society and shake my hand and hug me and laugh and cry with me. They are on pause, waiting, holding. They know less than me, and if my information comes to me at slow-modem speeds, then time must seem suspended for them.

The DOC—and I use that acronym instead of “prison” because I speak of the entire system—doesn't care. It doesn’t care about me, or my family, or my friends, or even itself. Once I enter the system, I become an abstract number or word on a form or a screen. My people are tourists spending money. The guards are robots that turn the keys and flip the switches. The system doesn’t have to wait and doesn’t understand waiting as a concept. Waiting doesn’t exist in the DOC, and so waiting doesn’t have consequences financially, mentally, emotionally, and physically. One month? Two months? Three months? I’ve waited in segregation for eight months. I’ve waited for guards to finish tearing up my cell to find contraband I didn’t have. I’ve waited for appeals that I knew would be denied. I’ve waited for a monster of a bunkie to come back into our cell. And now I’m waiting for a second chance. An opportunity. Maybe even redemption. Waiting isn’t so bad at the moment.

2. Letting Go

One thing prison teaches those who’ve been in for years is to value everything, even when it has no value. You never know when you’ll need it. You might never see it again. The DOC might ban or restrict it. It might be discontinued. And so on and so on the reasons roll in why you should keep things. Even when the reasons become flimsy and irrelevant, a weak reason is still a reason.

Books, cassette tapes, power adapters, folders, extra state issue clothes and linen, pens, little knick-knacks that aren’t supposed to exist in prison, a whistle, a pad of sticky notes, handwritten notes of ideas and numbers and dates and reminders, photocopies of anything, games, paper clips and clamps, thumb tacks, receipts. I can list a million different things we collect in here—that I’ve collected. And I’ve always thought, when my time comes to go home, I’ll throw it all in the hallway and walk out with the clothes on my back. It’s a nice thought.

I’ve given a number of things away to my friends, some right after I was resentenced. But then I started to think again. I thought of the stuff I own now that I will buy again later out there. Why should I give it away only to spend money on it again later? Altruistic reasons come to mind: It’s easier to get things out there in the free world than it is in here; to give is saintly; maybe someone needs it more than me. I’ve thought of these things and more but, there’s always a “but” in competition with reason.

Other people say it’s easier to get things out there, but is it really? Every commercial, magazine advertisement, catalog, or review always has prices and where you get something. It looks the same to me as it did 30 years ago. I’m not a saint. Does anyone really need graphic novels and manga? Because that’s most of what I keep. So I box it up and spend what little money I make in prison from being an academic tutor or a puppy caretaker or a painter and send it out because I’m embarrassed for people to see me walk out with it. Embarrassed because I know everyone’s looking at me and thinking I should leave whatever it is I’m taking with me behind.

And there’s more. My criminal case is over. No more appeals. No more resentencings. That’s it. But I kept all my court documents: requests for lawyers, transcripts, appellate briefs, mail disbursements, and so on. A record of the worst period of my life but I’ve kept it. And there’s still just stuff in my cell. All the things I’ve listed, I still have almost all of it. Notes and papers and folders and notepads. I have tablets and MP3s and clips and pens. I have a box full of knick-knacks. After almost 30 years, letting go of things is difficult. Changing a hoarder’s mentality is a challenge that many don’t really recognize. The reason why no one appreciates this problem is because once you realize you have it, you’re on the way out the door. The problem walks out the door, never to be talked about. Attachments. It’s hard to get rid of them.

3. Surviving

I no longer have a life sentence. I’m going home. I’m free. I have agency over my own life. I have only one bad feeling in all of this, one that I didn’t anticipate. Not fear of the outside world. Not being overwhelmed by the vastness before me. But the sadness. The sadness of not being with my friends anymore. I have this overwhelming feeling that I’m leaving friends behind enemy lines. I have spent almost two-thirds of my life in prison. All the friendships from my youth have faded into nothing more than nice memories, but in here, I have made many more friends. Some very good friends, some my brothers. And some of these guys do not deserve to be here. They have either done their time and are ready to move on or are good people who’ve made a mistake but the penalties keep on mounting.

I’ve been locked with Mario, my current bunkie, for ten years. We were—and still are—both part of an educational program where we bonded immediately. Once we arrived at our current facility, we decided to live in the same cell. Since then, we have both worked as academic tutors, we joined other programs like the Writer’s Block (a poetry and creative writing workshop), Chance For Life (mediation training), and became Prisoner Observation Aides (a program for suicide and self-harm prevention). We joined the art class and puppy program where we raised and trained dogs for the last seven years. Together, we have raised seven puppies, from when they were two months old to when they were 12 to 14 months old, teaching them manners and basic obedience and making sure they have the best life possible. I have singularly spent more time with Mario, my friend and brother, than I have with anyone else in my life. And the same is true for him. When my time to go comes, this will be the hardest, most difficult parting. Even as I write this, my eyes water with sadness.

How do you celebrate life and a new beginning when your family is being crushed under the heel of oppression? How do you plan to live and be happy when those you love are trapped in a purgatory of resentment and misery? One solution has been to just do stuff. I write, paint, play games, read, train puppies, and plot out my next endeavor. I hang out, play guitar, watch TV, listen to music, and talk on the phone. If I stay active and busy, I don't dwell on all the different things going home means—not just to me, but to everyone else around me as well. Another solution is to confront my feelings. To open up and talk about what’s bothering me. This has helped me. It allows me to vent the pressure that I feel. I can analyze and examine these feelings. Sometimes a rational mind can make sense out of what the heart is confused about.

Talking to others can also reveal what they’re feeling, especially when they’re typically introverted. Most everyone I know rejoices with the news of my impending freedom. But beneath that happiness is also sadness. I’m not the only one parting ways with friends. They are too. And the reasons vary. I won’t be a constant presence in their lives. I no longer relate to this world. I may even act differently. I find that talking helps. But I still can’t shake the feeling of making it out of here when there are others who deserve it just as much, if not more. This is—I think, I hope—the final struggle of my imprisonment. The feelings of joy and hope and sadness and despair.

4. A Moment to Think

on the yard is a bench

it sits in the grass

the grass trampled to dirt

from years of gym shoes

and state Oxfords

the view from one side of the bench

is buildings

and guards

and prisoners

and lights

no future

a promise of shakedowns

and pack ups

and fights

and stabbings

and pepper spray

and stun guns

the view from the other side

is chain link fence

and razor wire

and trees

the trees obscuring sight

of the world outside

of freedom

a secret

hidden

forgotten

invisible

the bench

is made of stone

heavy

impossible to lift

uncomfortable

but the view

not from the one side

but the other

makes it bearable

at least for a little while

5. The Last Oppressions

In these last months of my imprisonment, many things have happened that haven’t happened in a long time. It’s as though The Great Incarceration Machine is angry that I’m leaving. I was able to get through the COVID-19 pandemic without being quarantined, until a few months ago. I tested positive during a mass testing and was moved out of my cell that I had shared with Mario for years and put with some guy who snorted dope, washed people’s laundry at two in the morning and was afraid to take showers regularly. I wasn’t allowed to leave my cell except to use the bathroom or get some water. I couldn’t send out messages. The phone lines were jam packed from morning to night with other prisoners who were quarantined. The quarantine went on for three weeks. I was stuck in that cell for four months.

On three separate occasions, an emergency response team (ERT) composed of the meanest, rudest, anti-prisoner guards came in to search our persons and property with zeal. We were strip searched, our hands zip-tied behind our backs for up to two hours while the ERT guards stood over us with red SABRE pepper spray guns while the other ERT guards ransacked our rooms. Three times this happened. They degraded, threatened, and physically abused us.

We’ve been placed on lockdown status due to the actions of mental health patients in a neighboring unit. Different incidents, from breaking into the pharmacy to retaliating physically against staff, have caused the facility administration to lock the entire compound down. They never addressed the root of all these problems, just made us all suffer deprivation and confinement. We didn’t have showers, our meals were old and cold, and we had little to no communication with the outside world while stuck in our tiny, unventilated cells during heat advisory temperatures.

The rate of prisoners on suicide watch is way up. Some voluntary, some as punitive retaliation. Cells won’t lock. Drugs like “toochi,” fentanyl, suboxone, and others are the real pandemic killing people here. Gang violence. Nonexistent health care. Even the facility’s COVID-19 quarantine protocols are still in place. The Great Incarceration Machine wants to make me miserable, because it wants to keep me here. But I haven’t broke after all these years. I won’t break now, when I’m at the finish line.

6. The End

After all of it—the uncertainty, the waiting, the struggling, the holding on to the chains that have bound me for nearly three decades—I am ready to move on. To live, to love, to experience, to choose.

These years have not been “lost” years. Although I have wasted a lot of time, I have spent a number of years wisely. I have gotten my GED, I’ve learned to paint, I’ve honed my writing skills, learned how to play different musical instruments, cultivated relationships, facilitated classes, I’ve become a trained mediator, a suicide observation aide, and a puppy caretaker and trainer. I’ve had two books of poetry published and have a lot of poetry and prose scattered across the globe.

But while I’ve learned to navigate the world from behind walls and fences, will I have the same savvy when the world opens up, when the chasm of endless possibilities yawns its gaping mouth beneath me? I’m pretty sure I do. I have confidence. I believe in myself and those around me. I’ve never been slowed down by failure or the possibility of it, and I won’t start now. Even so, I find myself awake in my bunk some nights, wondering what’s next. Wondering if my plans will follow through, or does the world have something else in mind. I’ll find out soon enough. The months are dissolving into weeks and the weeks into days. More and more each day I think about the people I’ll be able to see that I haven’t seen in decades. The new people I’ll see for the first time. All the music I’ve missed out on all these years. The movies I haven’t been able to watch because they were rated R. All the places beyond the fences and walls that have been denied to me. Everything. Everywhere. Everyone.

There will be no more chains. No more handcuffs. No more bars. No more walls. No more razor wire. No more emergency responses. No more head counts. No more oppression. I’m ready.

Born in Detroit, Michigan, James D. Fuson is a writer and artist. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Washington Square Review at New York University, University of Michigan Press, the Detroit Institute of Arts, National Public Radio, Free School Press, Ugly Duckling Presse, and the Detroit Film Theater, among others.

Lead image: Scan of a page from James Fuson’s pocketbook, 2022

View next: Three Fold Commissions Amna Asghar