Ekphrasis

By Rachel Harkai

I started writing about art because I had a lot of feelings that I didn’t know what to do with. On Fridays in the fall of my senior year of college, I’d leave the liberal arts building at the center of the University of Michigan’s campus and walk State Street’s long hill down to the Huron River where I’d sit at the wooden bar in Casey’s Tavern, drinking a pint of draft beer and waiting to hear the low whistle of a train in the distance. An hour or so later, I’d stumble from the train’s steep metal steps into the fluorescent-lit yellow linoleum of Detroit’s Amtrak station and on into the derelict parking lot where my then-boyfriend would wait to meet me.

This particular then-boyfriend worked on Saturdays, and when he’d leave in the morning, I’d walk from his Cass Corridor apartment northeast across Woodward Avenue to the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA), where I’d spend whole Saturdays alone, wandering, searching the galleries for something that might strike my eye or my heart. As I ambled through the museum, I’d stop to make notes in my journal about anything that moved me. I was new to writing—new in a way where I could still marvel at my own ability to fashion something from nothing. I loved words and their specificity, and the discovery that language was a material I could shape and mold powered my every day like a subtle current. I was moving in those years, too, through the rush and drama of young romance. Inspiration was a precious stone waiting for me to uncover, and every emotion inside of me seemed like a poem waiting to be written.

Whether I had internalized it at the time, I was starting to write poems. Their early, haphazard drafts began in my journals. I’d walk away from an artwork with long, messy lists of colors, textures, shapes and materials. They’d grow punctuated later by snippets of narrative I’d superimpose onto the artwork, alongside open-ended questions. What note is he playing? I have scrawled in a notebook from sometime in 2006, underneath the heading “Degas, Violinist and Young Woman.” A book full of empty pages, the entry continues. Sadness. His eyes. Her parted lips. Notes on Giacometti, Cézanne, Rauschenberg, Stettheimer and so many others fill page after worn page carried with me through those years.

Eventually, I’d move to Detroit, and no matter which then-boyfriend I happened to be spending my time with, over the next fifteen years I returned to the museum again and again. Having visited one afternoon in—as best I can guess from the chronology of my notebook pages—early 2010, I strolled through the stone capitals and smooth arches of the museum’s Romanesque promenade downstairs, up past the Rivera frescoes and marble hallways lined with suits of medieval armor, beyond the delicate silver glint of Renaissance tea services. Turning then toward the next gallery, I saw a sculpture. The piece is about five feet tall and looks like a pair of wide-tooth combs standing in tandem. They rest almost supernaturally on their teeth. Hewn from wood and painted in red and black, each of the combs has six tines and is joined to the other at its spine by a lintel.

Geometric yet nonmathematical, the piece is distinctly imperfect. The combs’ pairs of tapered posts are nearly parallel—but not quite. Behind a crimson counterpart the twin row of darker tines seems to hide like a shadow. Uneven pigment is gouged and scuffed like a piece of furniture moved up and down a narrow flight of stairs too many times. Brushstrokes and drips of paint are visible, their colors variable—red bruises into fuchsia, black fades into mauve and purple.

The more attention you pay it, the more damaged the sculpture seems to become. Small pieces of tape have been painted over. Tiny knots and imperfections in the wood are darkened like sunspots. The tines that, at first, seem aimed like the needles of compasses grow more off-kilter and off-balance. One of them bulges a bit, hovering lightly off the ground, its edges asymmetrical and curvaceous. Everything seems, somehow, to tip—unstable and positioned dangerously as a body walking on its fingernails, balancing on the thinnest, most delicate endpoints of its appendages. These points are as thin as an eighth of an inch. That everything above them is heavy and might fall is the overarching feeling.

The sculpture, which was completed in 1949 by the French-born artist Louise Bourgeois, is called The Blind Leading the Blind. Once I became aware of this title, I found it impossible not to anthropomorphize the piece. The combs’ tines become six pairs of legs; the lintel joining them transforms into hips.

A bench sits directly in front of the sculpture. When you are stationary—gazing from a perch on this bench, for instance—The Blind Leading the Blind seems to capture movement. As in a photograph of soldiers in forced procession, the legs appear to march forward, their steps slow and effortful. But to think of the scene as frozen motion—as something to be viewed when still—is to miss the kaleidoscopic unfolding that occurs when moving around it.

With a step to the left, the bottom half of each rear tine emerges tentatively from behind its twin. Shift right of center and the alignment retrogrades, the tops of the recessed posts appearing chiastically, like a scissor with all blades and no handle. If you arc through all of the available one hundred and eighty degrees in front of the sculpture, its pairs of tines merge and separate over and over, like wavelengths going in and out of phase. Finally, at the opposite end of the sculpture, we are left again with a simple pair of legs—with two.

The sculpture’s title phrase is idiomatic, its earliest iteration appearing in Hindu scripture—the Katha Upanishad, specifically—which was written somewhere between 800 and 200 B.C.E. It surfaces also in the writing of the Roman lyric poet Horace during the first century B.C.E. We see it again, repeatedly, in the New Testament of the Bible—perhaps most pointedly in the Gospel of Matthew, wherein Jesus says of the Pharisees come to confront him, “Let them alone: they be blind leaders of the blind. And if the blind lead the blind, both shall fall into the ditch.”

Jesus is, it seems safe to say, speaking metaphorically—his expression carries what we might today consider an offhanded ableism. Sightedness serves figuratively here as a rather limited way of referring to one’s capability of discernment. The suggestion is that this perceived lack—this inability to discern—will lead, inevitably, to certain doom.

In 1568, Pieter Breughel the Elder, perhaps the most well-known of the Dutch Renaissance painters, completed his now-famous painting The Blind Leading the Blind. In it, we see a literal depiction of blindness’ multiplicity of meanings. Sometimes known as Parable of the Blind, the piece portrays six men trudging forward in a loose line. Both art historians and medical experts have written on the painting’s realism, diagnosing pathologies as specific as ocular globe atrophy and corneal leukoma from just looking at Brueghel’s incredibly realistic rendering of his blind men’s eyes.

The men are connected by chain of wooden staves held over their shoulders. Their bodies seem to tumble forward like dominoes falling, captured in various states of vertigo. Their facial expressions show emotions ranging from obliviousness to overt concern. At the front of the procession, the first of the men has fallen on his back, already collapsed into a ditch, while the next begins to trip and fall atop him.

Brueghel’s visual language explores both a physical and an emotional experience. And Bourgeois’ The Blind Leading the Blind does much of the same work—the difference being that because of her abstraction, her sculpture’s emphasis rests more on an overall feeling of impending danger than on any presumed pathology causing it. Which is to say that if we were able to strip Bourgeois’ piece of its title—to lose its scriptural cliché—the visual aspects of the work would remain suggestive of one of life’s great truths: we have no way of knowing what lies ahead of us, and this condition of uncertainty often feels as precarious as it is universal.

In the early 1940s, with the realities of World War II disconnecting her from friends and family in France, Louise Bourgeois and her husband, Robert Goldwater, moved with their children into an apartment building in Manhattan. It was during this period that she began using the roof of the building as an open-air studio. Bourgeois’ work from the time includes engravings and sculptures—among other media—and is marked by series of human-sized, totemic, carved wood figures that she dubbed Personages. The tall, slender shapes of the series mimic the vertical exaggeration of Manhattan’s skyscrapers. Yet despite their height, each piece stands precariously on a very narrow, needle- or spindle-like point, lending a feeling of pervasive precariousness.

In early exhibitions Bourgeois displayed Personages directly on the floor. As how removing a painting from its frame might, to present her sculptures without a base removed the artifice that separated the viewer from her works. Visitors could move freely among the sculptures, as though walking through a crowd.

“They represent people,” Bourgeois said of the totems, which she made as physical stand-ins for friends and family who remained in France. “They are delicate as relationships are delicate. They look at each other and they lean on each other.” Some of the individual sculptures stand alone; others huddle in small clusters. The figures are, as Bourgeois emphasized in her first published statement on the work, made to be seen in groups. As such, the Personages build the same tension one might feel as a human positioned within any larger group: they emphasize the truth that to be among others is to be simultaneously physically together and existentially alone. And what group of individuals could be more archetypical—could hold this tension more poignantly—than the family of origin?

For Bourgeois, childhood was a minefield of familial conflicts and traumas, the most impactful of which was her fraught relationship with her domineering and adulterous father. In an illustrated autobiographical text called “Child Abuse,” which was published in the December 1982 issue of Artforum, Bourgeois spoke openly about her father’s sexual relationship with her young governess, Sadie Gordon Richmond, and the lasting impact of her family’s dysfunction on her motivations to make art:

“Everything I do was inspired by my early life. On the left, the woman in white is The Mistress. She was introduced into the family as a teacher but she slept with my father and she stayed for ten years. … So what role do I play in this game? I am a pawn. Sadie is supposed to be there as my teacher and actually, you, mother, are using me to keep track of your husband. This is child abuse. Because Sadie, if you don’t mind, was mine. She was engaged to teach me English. I thought she was going to like me, instead of which she betrayed me. I was betrayed not only by my father, damn it, but by her too. It was a double betrayal.”

The sexual whims and emotional tyranny inflicted by Bourgeois’ father dominated the household throughout her childhood. As his affair with her young nanny continued, Bourgeois’ resentment grew over having to—as she might have phrased it—turn a blind eye to the entanglement. Over the course of an artistic career spanning eight decades, Bourgeois’ work grew defined in many ways by a retrospective gaze—one through which she would repeatedly exhume childhood feelings of abandonment, shame, anger and distrust.

On January 3, 1952, Bourgeois entered the office of Dr. L. Henry Lowenfeld, a second-generation Freudian who she would engage for psychoanalysis—at times up to four times a week—until his death in 1985. Throughout this thirty-plus-year relationship—as was revealed in four boxes of previously unpublished writings discovered at the end of her life—Bourgeois’ analysis delved into dreams, desires, symptoms, anxieties and memories. The process was a figurative exhumation of the past, and, through it, self-examination offered hope that repressed emotions might one day be purged cathartically from her unconscious mind.

Parallel to her analysis, artmaking was another outlet through which Bourgeois delved obsessively into her past again and again. And while she worked in many media throughout her career—including drawing and printmaking—sculpture, in particular, lent her childhood traumas a tangibility that Bourgeois, as she put it, “could hack away at.” Her 1968 sculpture Fillette, the title of which translates from the French to “young girl,” consists of an almost grotesquely realistic latex-and-plaster phallus that dangles from a thin hook. In her 1974 installation The Destruction of the Father, similarly cast, latex-coated cuts of meat sit sacrificially amid a tableau of sexually evocative soft sculptures, while the room that holds them—suggestive of both a dining room and a bedroom—is bathed nightmarishly in red light.

Retrospection and return, employed as formal processes, effected thematic refrain throughout Bourgeois’ career. She returned, for example, to a second version of her original hanging phallus, Fillette, sometime between 1968 and 1999. The piece—named almost reconcilingly Fillette (Sweeter Version)—was eventually cast in 2001. Whereas The Destruction of the Father engaged a childhood fantasy of destroying her philandering dad by serving him up at the dinner table, what we see across her career might more accurately be categorized as a meticulous re-construction of the emotional landscape that Bourgeois suffered beneath him.

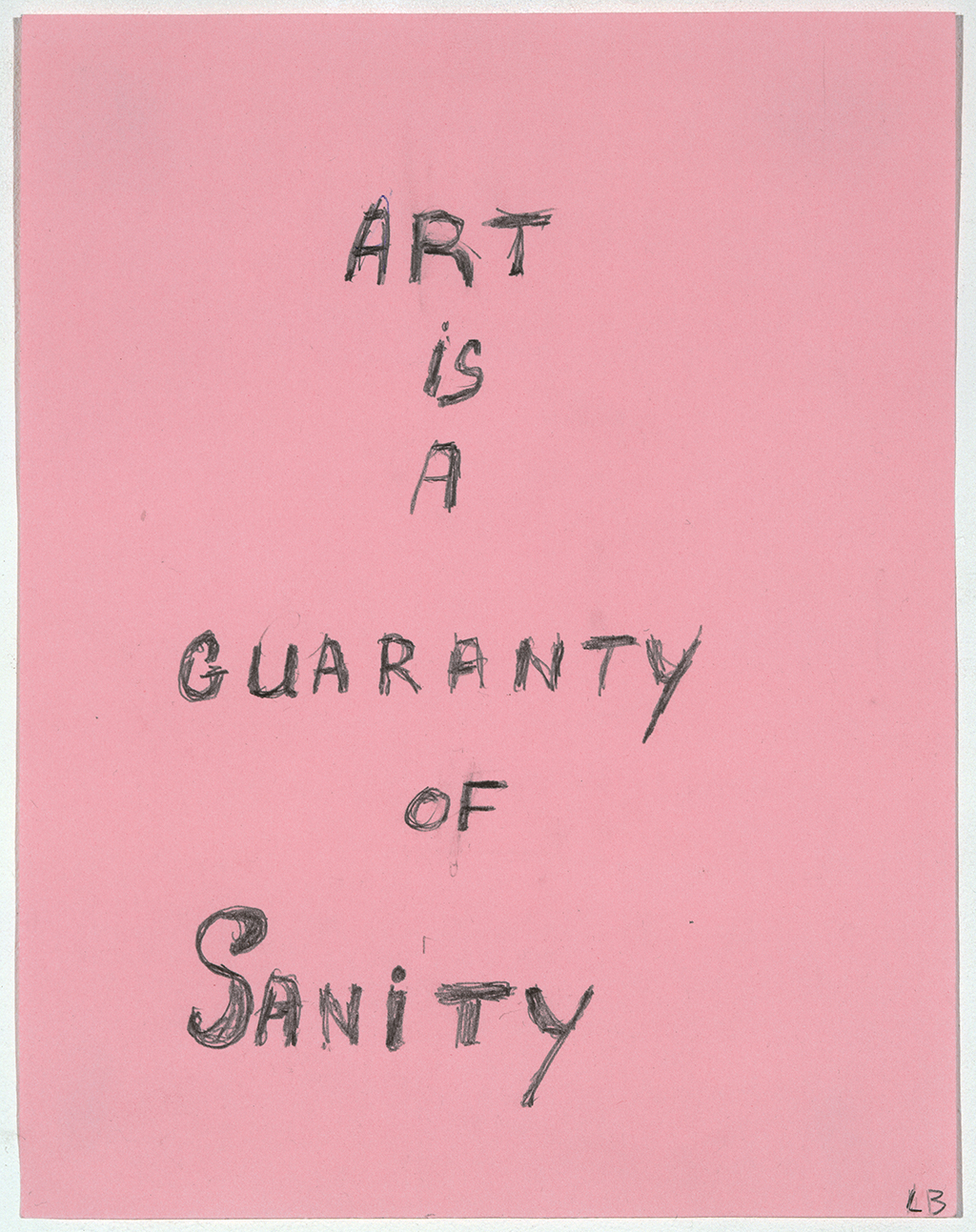

Artmaking became as valuable a therapeutic tool for Bourgeois as her analysis. She engaged with creation as though it were an exorcism. “Art is a guaranty of sanity,” she is famously known for having coined in a pencil drawing that commemorates the phrase on pink paper. “Every day you have to abandon your past or accept it,” Bourgeois once said, “and then if you cannot accept it you become a sculptor.”

Bourgeois made five versions of The Blind Leading the Blind that are housed in various museums around the world, including the Detroit Institute of Arts, the National Gallery of Australia, and the Hirshhorn in Washington, D.C. In a 1988 interview with Donald Kuspit, an art historian known as one of the field’s foremost practitioners of psychoanalytic art criticism, she spoke at length on the genesis of the series:

“The reason this blind army of legs does not fall, even though the legs are always afraid of falling, since they come to a point, is that they hold on to each other. This is exactly what I felt when I was a child, when I was hiding under the table. My brother was following me like a shadow; I was blind with fear and so was he. … [T]here we were under the table and we would look. I don’t know what we were looking at. But I was watching the feet of my father and mother from under the table, while they were preparing the meal. … I decided that the outside was not friendly. And I was afraid, simply afraid. … I didn’t understand why they were walking around the table. Why would one pair of legs interfere with the other visually, physically? There were their legs and the table’s legs. … I had to make an object of, physicalize this problem.”

Bourgeois’ reflections on childhood focus largely on overarching feelings of fear and powerlessness—on the sense that she had no capacity or authority as a young girl to give voice to her pain. She therefore recorded her thoughts and experiences in a diary, a practice that she began at the age of twelve and would continue for the rest of her life. As a compulsive writer, text, wordplay and translation filtered heavily into her artwork, evidenced in the ways she deployed language both content-wise and in her frequently clever titling.

In her first art book, He Disappeared Into Complete Silence, published in 1947, nine surrealistic and largely geometric engravings are presented alongside short parables Bourgeois wrote. The text beside plate number seven reads:

“Once a man was angry at his

wife, he cut her in small pieces,

made a stew of her.

Then he telephoned to his

friends and asked them for a

cocktail-and-stew party.

They all came and had a good

time.”

While Bourgeois’ text here lives in story form, her play with language was at other times so narrow as to focus on the shifting of individual letters. In other works, for example, she toys with the binary built by changing a single letter in the French words “moi” and “toi”—translating to “me” and “you.” Enacting similar wordplay, two of her pieces from 1997 share an identical title: Seamstress Mistress Distress Stress. One of them is a nine-foot tall, almost mobile-like steel rack from which hang cloth garments, a tapered rubber cylinder, blown glass bulbs and other mixed-media assemblages. The other piece is composed of simple serif lettering on paper; Bourgeois aligns the title’s words along the right-hand margin so as to emphasize their second syllable:

Seamstress

Mistress

Distress

Stress

The ancient Greeks made a rhetorical exercise of writing about art. The name for their practice, ekphrasis, derives etymologically from ek meaning “out,” and phrasis meaning “to speak.” Ekphrasis—or the verbal representation of visual representation—was originally intended to deploy highly detailed language, describing a tableau with vividness and precision that would rival the original artwork. That this type of extended description was historically prescribed as an exercise is testament to the exceeding difficulty of translating the sensory into language. One of the most referenced examples of ekphrasis comes from Homer’s Iliad, wherein the description of Achilles’ shield becomes part of the narrative. The magic of this particular passage from Homer, along with many other examples of the form—such as Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, for instance—is that the urn and the shield were never, in fact, real objects available to reference. Thus, their authors’ vivid descriptions evidence not only incredible lexical skill, but extraordinary powers of persuasion and imagination.

By 2010, I was just beginning to gain enough confidence to claim my identity as a writer and was invited that autumn to participate in a group reading in the galleries of the Detroit Institute of Arts. The poems I read were inspired by Egon Schiele paintings, and a Donald Sultan piece called Oranges on a Branch March 14, 1992. I read one final poem beside a tall, pointy wooden sculpture by Louise Bourgeois; it was called The Blind Leading the Blind.

Typical of the ekphrastic tradition, my poem leaned heavily on description, though its imagery was steeped in simile and metaphor. “Like boatsmen summoning sea legs, or children,” it read, “we muster balance then stop / briefly to rest on one another before moving / steadily on.” The poem incorporates sensory description, too. In my notebook entry from the first time I saw Bourgeois’ sculpture, I can make out two faded phrases: that this says something of blindness / that this says something of touch.

In part, writing on The Blind Leading the Blind was a way to imagine what it might be like to live without my sense of sight. The poem references philosopher Denis Diderot’s 1749 text Lettres sur les aveugles à l'usage de ceux qui voient—Letter on the Blind for the Use of Those Who Can See—which I had read in a literature course in college in the original French. Among other avenues into blindness, Diderot examines the potential use of other senses as aid for people with impaired sight. He tells how a blind man from the town of Puiseaux would judge “his nearness to the fire by the degrees of heat … fullness of vessels by the sound made by liquids which he pours into them … the proximity of bodies by the action of the air on his face.” Diderot’s words were poetry to me.

At the risk of leaning too heavily on the figurative notion of blindness as metaphor for something missing, the context for my writing was that I was suffering, at the time, a particularly rocky romance with an on-again, off-again boyfriend. Our arguments were infrequent but when they happened they were loud and brutal and hard for both of us to come back from. And in those difficult years, a larger notion alluded to by both Diderot and Bourgeois—of managing, despite struggle, to survive difficulty—galvanized me. “I don’t know where we’re going,” I wrote in the poem, “or how / to make this a straight line—sometimes / I think this so loudly that I believe I can feel you / hearing me.”

By writing that poem—from the hours I spent sitting with Bourgeois’ sculpture, to those spent laboring later over every word I chose around it—I experienced one of the great conundrums of artmaking for the first time: that one can be infinitely proud of having completed a piece without ever growing to like it. I never felt good about the poem, and after the reading it stayed buried deep in the subfolders of my laptop. Until one evening—years later—I agreed, hesitantly, to let a few close classmates from my graduate school writing program workshop the piece at a dinner I’d hosted. That night we’d discussed writing we thought to be ekphrastic, and after dinner we each shared poems aloud. After hearing mine, a classmate commented, gently, “This poem isn’t really ekphrastic.” Though I was taken aback at the time, my friend’s remark was right.

In a 1954 artist statement, Bourgeois wrote on the challenge of writing about art:

“An artist’s words are always to be taken cautiously. The finished work is often a stranger to, and sometimes very much at odds with what the artist felt, or wished to express when he began. At best the artist does what he can rather than what he wants to do … the artist who discusses the so-called meaning of his work is usually describing a literary side-issue. The core of his original impulse is to be found, if at all, in the work itself.”

Bourgeois’ sculpture, I realized through my friend’s insight, was just my so-called “literary side issue.” Rather than offering an ekphrastic description of Bourgeois’ artwork, I had written a poem that was instead a vivid metaphorical account of my experience of love as difficult. I was not describing what I saw; I was describing what I felt. Relationships had always been, for me, like stumbling through the dark. In them I felt I was failing and falling and picking myself up again. And the poems I had called “ekphrastic,” I realized, were barely about art at all.

Nearly ten years after reading my poem The Blind Leading the Blind at the Detroit Institute of Arts, I enrolled in a weekend-long seminar on art writing. At the time, I was suffering a long fallow period in my writing. Months, if not years, had passed since I had really felt inspired. For the seminar’s workshop component, we were assigned the task of writing about a piece of art. So, in search of a spark—as had been my way for so many years—I returned once again to the museum.

As I wandered through the galleries, my thoughts turned to the Bourgeois sculpture I had written about many years earlier. Why, I wondered, had that poem never felt successful? How would it feel to view the sculpture again? I decided to take up a post on the bench in front of it once more. And after an hour or so of scribbling in my notebook, I walked away with the sick notion that I would write an essay for my workshop that unpacked—once and for all—why my original poem had been a failure. The point of the essay, I thought, would be that artists are compelled to return to their shortcomings again and again. And as I walked away resignedly through the galleries on my way back to the car, I turned around a corner and stumbled, suddenly, into a long, dark room I didn’t recognize from my previous visits.

Its walls and floor were barely illuminated in red light. Whatever artwork I had been used to seeing there had been recently deinstalled, replaced by what appeared to be eight black, imageless frames. Hung side by side in a row, they were made of what appeared to be dark glass. Each rectangle was sized and oriented slightly differently. Their frames seemed to sink backward into the wallboard like punched holes, and nothing about them seemed regular. The whole encounter felt accidental. At the back of the room, a few benches had been pushed flush against the wall, as though in storage. That I was completely alone there gave me the feeling that I had walked into someplace off-limits—that I was seeing something I wasn’t supposed to. And yet, it appeared there was nothing to see at all. What were these dark paintings?

As I walked slowly, closer, a red light flashed suddenly in the nearest frame. I stepped back. The light disappeared like an apparition. Astonished, I moved delicately through the long space. As I passed each frame, in it a piercing red image would materialize all at once like a light switched on. From each pane of black glass, a crimson something—an image—would appear abruptly from nothing. For a few minutes I simply walked back and forth and back again, past each of the frames, so enamored with the illusory magic of their visual trick—with the simulation of suddenly, for the first time, seeing—that I hardly gave attention to their subject matter at all.

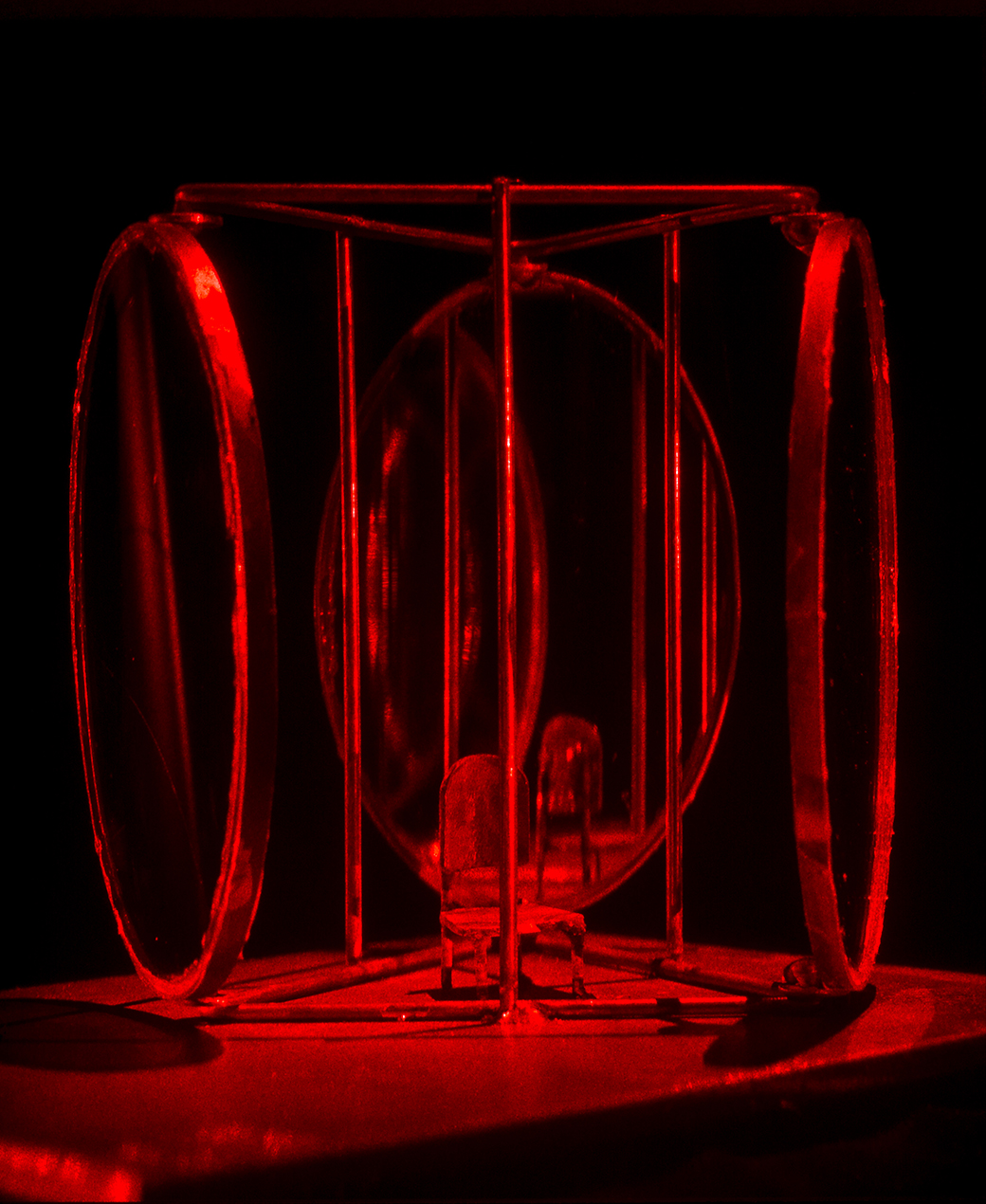

I noticed soon, though, in one frame, a chair placed on a concrete pedestal. Beside the pedestal, a small set of stairs proffered itself toward me so closely as to almost invite me into the glass, luring me to walk closer. But the chair, confined under a transparent bell jar, was inaccessible. A small margin of the pedestal circumscribed its perimeter, as though to suggest I should walk on it all the way around the bell jar—that the chair was meant to be viewed from all angles.

In another frame, a different, smaller chair was surrounded on three sides by large, double-sided mirrors. The mirrors’ angles made it seem that if you, the viewer, were to shift ever so slightly to the side, you might catch a glimpse of yourself reflected there. But each time I moved—in the exact moment my face should have appeared—the entire crimson image would disappear.

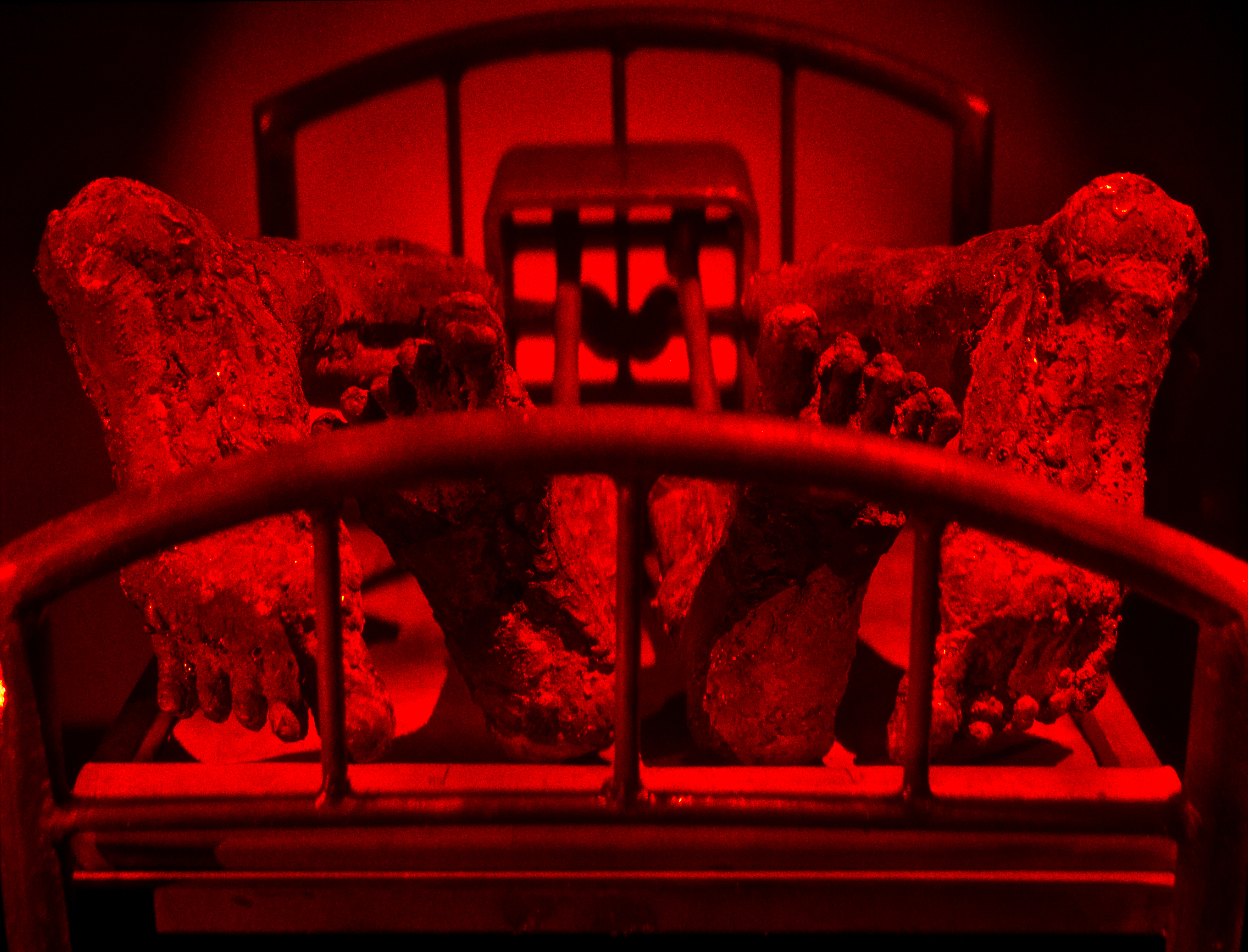

As I progressed past the series of frames, body parts began to appear. In a few of the plates, two pairs of disembodied feet—amputated just above the ankle—lay in various entanglements on a metal bed. Where the bones of their tibias and fibulas should have been, thick metal rods were attached instead to a box, suggestive of long-dead body parts retrofitted like crudely reanimated puppets. Their flesh seemed to glisten and rot at the same time. And the bed—like a cage—had no mattress, no fabric, no softness.

“That’s suggestive,” I heard a nearby voice blurt. Beside me a museumgoer gazed puzzlingly at the grotesque, black-and-red feet, and I returned suddenly back into my body. I was no longer a lost bystander who’d stumbled accidentally onto the scene of some ambiguous, haunting crime. I was in a gallery again, looking at art. That these chairs and legs had—by some feat of optics, or science, or magic—materialized before me like threadbare ghosts of a long-abandoned home, besieged me with awe. I walked back toward the entrance of the room to read the museum label pasted in its corner. It read:

Louise Bourgeois

Untitled, 1998-2014

Suite of 8 Holograms

In 1994, the Brooklyn-based artist Matthew Schreiber—a long-time studio assistant of James Turrell, known now for his light-based work featuring holograms and lasers—co-founded an endeavor called C-Project. Over the span of five years, Schreiber and C-Project would engage seventeen artists—including John Baldessari, Chuck Close, Roy Lichtenstein and Louise Bourgeois, among others—in holography-based collaboration. “What might this artist create,” the studio asked, “if they knew how to make a hologram?” As Schreiber told me over the phone late in 2018, the project became a way “to get inside each artist’s mind.”

Most people might think of holograms as optical illusions. For instance, consider the famous Tupac Shakur “hologram” in which a three-dimensional reanimation of the rapper enraptured a spellbound Coachella audience in 2012 with a modern adaptation of an old stagecraft technique known as “Pepper’s Ghost.” Bourgeois, according to Schreiber, was not at all taken by such gimmicks. Schreiber said that this was because she treated holography like she would have any other material—as though it were something to be hewn, like a chunk of stone. Among the many artists that worked with C-Project, Schreiber describes Bourgeois as uniquely comfortable with the medium.

The series of holograms began with maquettes—small sculptures of chairs and mirrors and bell jars—sized as though made for a dollhouse. The maquettes were then documented in a specialized darkroom, where Schreiber used lasers to illuminate them. The wavelengths of light would bounce off of Bourgeois’ minute sculptures onto glass plates treated with a silver emulsion. In the final holograms, the entire light field is spectacularly recorded, documenting in two dimensions how each maquette had been three-dimensionally placed and lit.

Schreiber described the process to me by comparing captured wavelengths of light to the aftermath of a pebble thrown in a lake. “What’s recorded on the glass,” he said, “is like ripples of water on the shore. The shape of the sand shows how the light changes.” Schreiber recalled, too, how Bourgeois’ approach to color was unique among his collaborations. She was aware enough, he noted, to ask, “What is the raw state of this material?”—the material in its purest form, at its original wavelength, being a piercingly red laser light.

After Bourgeois’ death in 2010, C-Project completed her series of eight holograms posthumously, and, following a 2017 showing at Cheim & Reid in New York, the plates made their way quietly into the collection of the DIA. In their final form, the three-dimensional depth captured in each hologram might be best evidenced by the fingerprints left from viewers who’ve ignored warnings not to touch. I imagine grown adults so entranced by the images as to try using their hands to reach inside the frames. Whereas from up close, when walking past each plate, its individual image appears and disappears like the brain recalling something out of darkness, from the very back of the room—where one might perch on the lonesomely arranged benches—all eight images become visible at once. Observed concurrently, their weight is as heavy and haunting as a lifetime’s worth of memories all conjured simultaneously.

With early works like The Blind Leading the Blind, Bourgeois wrought raw, primitive materials into abstract representations of her pain. Her untitled holograms are strikingly futuristic and more vulnerably explicit. Though working in them with contemporary technology, Bourgeois was nevertheless returning to her same childhood pain. In the holograms, we see her anguish roused again, cast forever in a hellish, crimson light.

That at the end of her life, Bourgeois’ work still circled around her childhood traumas might suggest that her hope for catharsis—won through therapy or otherwise—was never realized. And yet, I suspect somehow that Bourgeois would not consider this a failure. In a 1962 essay addressing Freud, strikingly, as an art collector, Bourgeois wrote, “To be an artist involves some suffering. That’s why artists repeat themselves—because they have no access to a cure.”

What, then, makes an artwork successful? I used to think, naively, narrowly, that each piece of writing I made needed to be self-contained. Yet I was compelled, again and again, to return to my poem on The Blind Leading the Blind. I felt a need to rewrite it and to unpack it—that there was always, somehow, more to say. I initially made this mean that my poem had been a failure. But what I discovered, gradually, over a decade or more spent returning to the work of Bourgeois—who spent her entire career returning to the same traumas—is that it might take a whole life to say it all, or even longer.

I am thinking now of the etymological evolution of the English word “essay,” derived from the French verb essai—meaning “to try.” In viewing Bourgeois’ massively moving body of work, we see someone trying to understand themselves. Bourgeois’ willingness to return to her inspirations—whether the experience of doing so was traumatic or ecstatic, or both—reveals her as indomitable, as an artist who understood repetition as the true development of voice.

Through Bourgeois I have learned, too, that communicating what makes an artwork beautiful is a hard job. For that we have ekphrasis as a tool. But explaining why it is beautiful might be the ultimate illustration of the subjectivity of human experience. The ekphrastic poet tells us what they see. By describing art, we learn that the reasons why it matters to the viewer aren’t always visible. Trying to describe our connection to an artwork—that’s the place where ekphrasis spills outward into art of its own.

Rachel Harkai earned a master of fine arts degree in writing from the University of Michigan Helen Zell Writers' Program. A finalist for the 2019 National Poetry Series, she was runner-up in the 2016 92Y Discovery Poetry Contest and the recipient of a 2010 Kresge Artist Fellowship. Her poetry and nonfiction have appeared or are forthcoming in Narrative Magazine, Salmagundi, Michigan Quarterly Review, DIAGRAM, Smartish Pace and elsewhere. Harkai currently serves as the volunteer coordinator for Room Project, a space for women and non-binary writers in Detroit.

Lead image, Louise Bourgeois

Art is a Guaranty of Sanity, 2000

Pencil on pink paper

11 x 8 1/2"; 27.9 x 21.5 cm.

Photo: Christopher Burke

© The Easton Foundation/VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Fig. 2, Louise Bourgeois

The Blind Leading the Blind, 1947-1949

Wood, painted black and red

67 1/8 x 72 x 12 ½”; 170.5 x 182.9 x 31.8 cm.

Collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts

Photo: Courtesy the Detroit Institute of Arts

© The Easton Foundation

Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Fig. 3, Louise Bourgeois

Untitled, 1998-2014

Suite of 8 Holograms

Plate 7: 11 x 14"; 27.9 x 35.6 cm

Collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts

© The Easton Foundation

Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Fig. 4, Louise Bourgeois

Untitled, 1998-2014

Suite of 8 Holograms

Plate 5: 11 x 14"; 27.9 x 35.6 cm

Collection of the Detroit Institute of Arts

© The Easton Foundation

Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Read next: Amina Teaches by Luke Stewart