Sweet Extinction

By Francis McKee

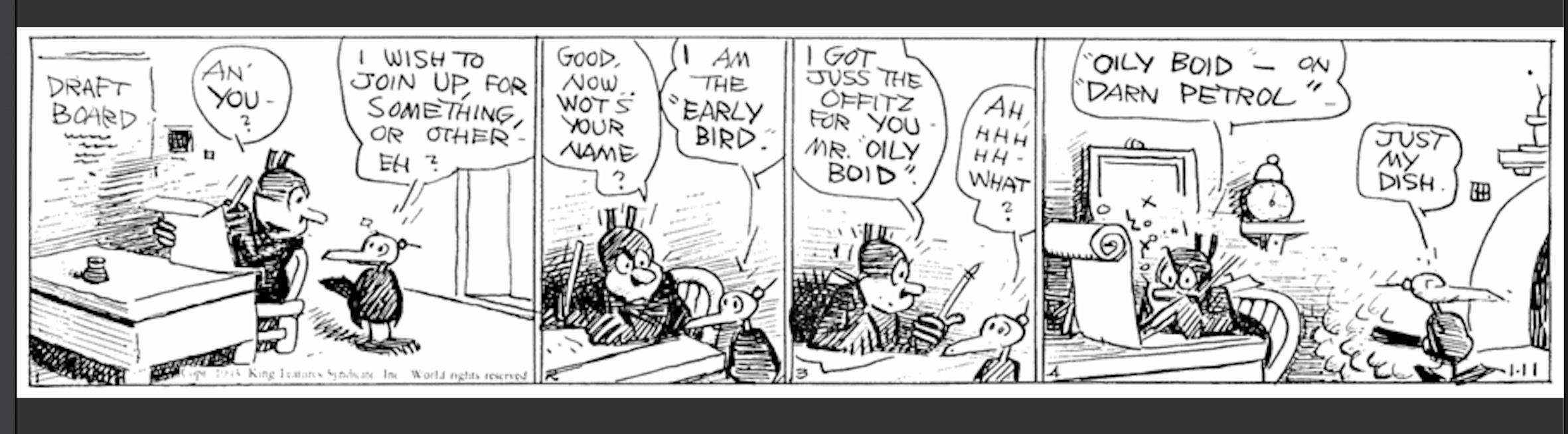

George Herriman’s comic strip Krazy Kat ran in William Randolph Hearst’s newpapers from 1913 to 1944. It began, though, as a footnote in another of the artist’s strips, The Dingbat Family, in 1910. Running in the gutters of that strip, a tiny cat found itself pursued by an even smaller mouse who, on July 26, 1910, threw his first brick at the cat’s head. While the Dingbats moved on, and their house was demolished, the cat and mouse thrived, finding themselves transplanted from the city to a much more isolated landscape in Monument Valley. Bricks continued to be thrown and there was even a local brickmaker, a dog called Kolin Kelly, who supplied Ignatz the cat with his daily ammunition. Another dog, Offissa Pupp, exerted most of his energy attempting to prevent those bricks reaching their target, often to the chagrin of Krazy, who interpreted each missile as a sign of love from the beloved mouse. Over the years, other characters came and went but always on the margins of this love triangle and always bounded by the repetitions of Herriman’s basic plot: Krazy (ambiguously described as both he and she) would incite the frustration of Ignatz, a brick would be thrown, and Pupp would march the mouse to jail.1

The potentially claustrophobic plot replays over 33 years in the same landscape and somehow generates a mental space that is both beyond time and yet allows the real world to seep in. The paradox of the comic lies in its context: Herriman’s strip was published in the sprawl of newspapers owned by Hearst; its daily appearance sustained by the most sophisticated media information delivery of the day. The strips were praised by such writers as ee cummings and Gertrude Stein, filmmakers including Hal Roach and Frank Capra, and even American presidents, such as Woodrow Wilson, who made a habit of reading the strip before immersing himself in war cabinet meetings. In this twentieth century maelstrom of daily news, Krazy Kat prised open a window into a surreal landscape of mesas, desert, cacti, big skies and, from 1935 onwards, blazing color. This was a place where everything was in continual flux: trees morphed from one panel to another while daylight turned to night and deserts transformed into theatre sets.

Herriman’s comic geography was ahead of its time. It was only in the 1990s that a British academic, Doreen Massey, began to outline a theory of place as a process. In her book, For Space, she argues for “Space as the product of interrelations; as constituted through interactions, from the immensity of the global to the intimately tiny.” Massey states that “space on this reading is a product of relations-between, relations which are necessarily embedded material practices which have to be carried out, it is always in the process of being made. It is never finished; never closed. Perhaps we could imagine space as a simultaneity of stories-so-far.”

In the early years of the twentieth century, the world of Krazy Kat already exemplified her arguments and that may be a consequence of George Herriman’s very particular situation. In 1972, Ishmael Reed dedicated his novel Mumbo Jumbo to, among others, “George Herriman, Afro-American, who created Krazy Kat.” This was news to everyone, as Herriman had effectively passed as white throughout his life. Recent biographical research has gradually fleshed out Reed’s claim and established a fascinating backstory for Herriman’s family in New Orleans. It has also cast the comic strip in a new light, where the characters’ dialogue is seen to have roots in minstrelsy skits; Krazy questions his color, and the dynamics of immigration and race flow through the slender plotlines.

This new perspective on Herriman and his creations has also enabled readers to rethink the world of Krazy Kat as they pore over the strips and, in a sense, treat the artwork as something that may reflect reality. The strip is set in the timeless landscape of Monument Valley, exploiting the mythic qualities of the desert and mesas long before John Ford would do the same, and there is a thread of references running through the years that posit a cyclical process of death and return. A version of the Navaho wheel of time also appears in almost every Sunday strip and, in a 1917 episode, Herriman surveys the landscape and its characters, declaring that “The Clocks of the Universe are chiming the hour of ‘now.’”

Despite this admirable, zen-like approach to time, it’s clear that the horrors of mortality—aging, grief, and the shock of death—intrude. The unexpected death of Herriman’s 30-year-old daughter Bobbie in 1939 was marked in an elegiac strip on December 10 when a small star falls from the sky: “a little ‘star’—just a baby ‘star’—una estrellita caida—”. Krazy catches it, returns it to the heavens by inflating pillow case over the fire to improvise a balloon, and falls asleep. His friends later find the pillowcase and a note beside him that reads, “I’m back home and happy—thanks—Twinkie.” The scene betrays a sense of loss that neither philosophy nor religion could alleviate. And in the few remaining years of his own life, the artist’s strip became subtly darker as global events began to seep into its panels.

Life During Wartime

Perhaps the greatest clock of the “now” was newspaper empire of William Randolph Hearst, proprietor of roughly 30 major newspapers across the United States. Many of those papers carried Krazy Kat, often at Hearst’s insistence, despite the reluctance of his editors who felt it was too odd for their readers. The irony then is that Herriman’s desert landscape is embedded in newspapers teeming with reports of political upheavals, wars, social turmoil, fashion, and society small talk. Time is measured in those pages by the incessant chatter of typewriters and tickertape machines.

As the artist’s health declined, the papers were increasingly focused on the United States’ entry into the second world war after Japan’s Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941. Tensions had been rising in the Pacific between Japan and the United States for some time as Japan attempted to expand its territory and the United States maneuvered against this strategy. Along the West Coast, city blackouts were introduced in early 1941, though one of the first experiments in Seattle led to chaos in the streets when a mob gathered to target businesses that hadn’t turned out their lights. In a 2013 essay on that riot, Duane Colt Denfield writes::

“The blackout went into effect at 11:00 p.m. on the night of the 8th. Just minutes after 11:00, a crowd formed at 4th Avenue and Pike Street, where the lighted letters of the Foreman and Clark men's clothing store at 401 Pike were clearly visible. The crowd jeered and started throwing objects to break the lights. It took nearly one hour for rioters to break most of the lights of the twelve letters making up the sign. During the attack a store employee arrived and with a ladder climbed up to the second-floor sign and extinguished the remaining lights. The crowd then moved on to other visible lights.

… A leader emerged when Ethel Chelsvig (1922-death unknown), the wife of Seaman Raymond Chelsvig (1909-1967), a boiler technician on the destroyer USS Kane, urged the crowd on. She loudly proclaimed that she was married to a Navy man and that he was out there fighting. Chelsvig asked the crowd if they were ‘going to stand by while these lights threaten the very life of our city?’ and shouted "Break them! Turn them out’ (’Glass-smashing Mob’) …

... Two hours after it started the police ended the riot and announced over loudspeakers that anyone on the street after 1:00 a.m. would be arrested. The crowd then dispersed. Fourteen businesses had a total of 26 broken windows. The reports of Japanese aircraft and ships had turned out to be false.”

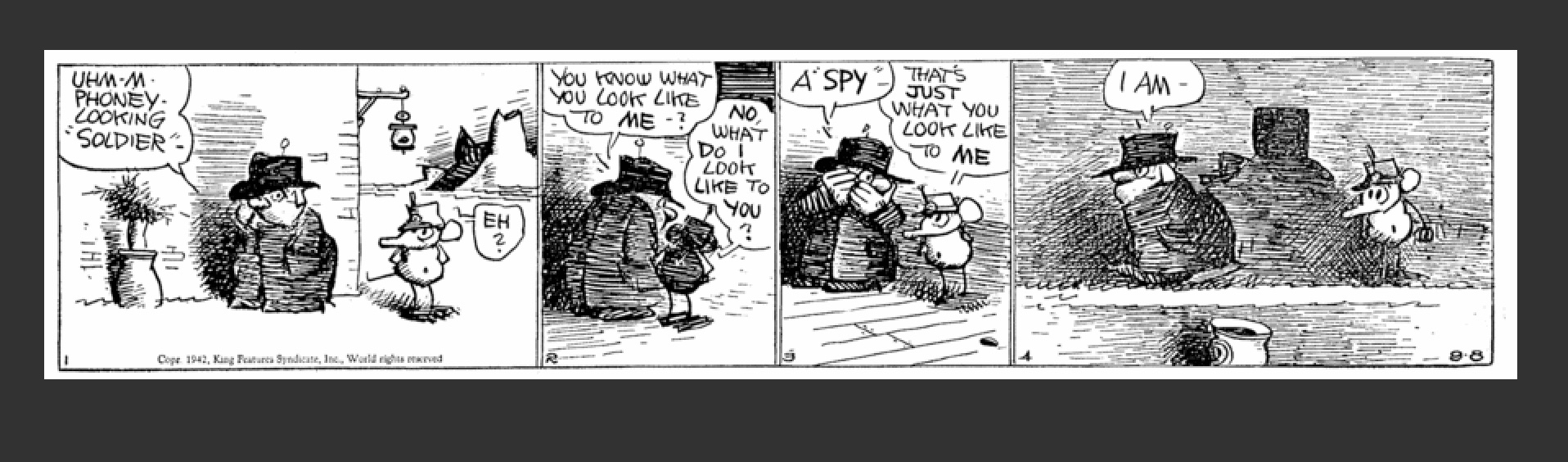

The impact of the nation’s new war footing quickly began to seep into the world of Krazy Kat. From 1942, the daily strips began reflecting the new domestic climate. Offissa Pupp attempts to enforce blackouts while Ignatz is subject to a curfew and typical Krazy scenarios bend to accommodate an emerging militaristic world. The inhabitants of Cocinino Country are subject to interviews for the draft while the most common new theme pondered is patriotism. Spies infiltrate the strip and are viewed with both fascination and suspicion. And on the horizon, throughout 1942 there is a fear of mutiny. Draft registration was introduced in April 1942 and Herriman registered (as white); though, aged 61, it was unlikely he would be called up.

Across the East Coast of the United States. there was a panic over spies infiltrating the nation, spurred by the discovery of Operation Pastorius, a German plan to sabotage key economic targets and spread a wave of terror across the country. The plan was slapdash and quickly foiled when one of the eight saboteurs defected, surrendering himself to the FBI in Washington. In the febrile atmosphere of the early days of war, it was enough to stir fear in the population.

“The country went wild,” Francis Biddle, then attorney general, later wrote in a memoir. Hundreds of German aliens were rounded up and others, suspected of spying, were arrested. The Justice Department banned German and Italian barbers, servers and busboys from Washington’s hotels and restaurants because three of the would-be saboteurs had worked as waiters in America.2

In this atmosphere, patriotism became the mantra and it permeates the world of Krazy Kat as the characters deal with enforced changes “for the duration,” a popular euphemism for wartime.

One very controversial development of this situation was the rounding up and internment of U.S. Japanese Americans in a chain of concentration camps. Herriman, at that time, had a young Japanese man known only as William living in his house, presumably to help him as he became increasingly infirm.3 William was incarcerated sometime in 1942 or 1943 and no more is known of him.

Anti-Japanese discrimination across the States was undisguised. In Herriman’s hometown, the Los Angeles Times published in 1942:

“The Japs in these centers in the United States have been afforded the very best of treatment, together with food and living quarters far better than many of them ever knew before, and a minimum amount of restraint. They have been as well fed as the Army and as well as or better housed … The American people can go without milk and butter, but the Japs will be supplied.”

And later in 1943:

“As a race, the Japanese have made for themselves a record for conscienceless treachery unsurpassed in history. Whatever small theoretical advantages there might be in releasing those under restraint in this country would be enormously outweighed by the risks involved.”

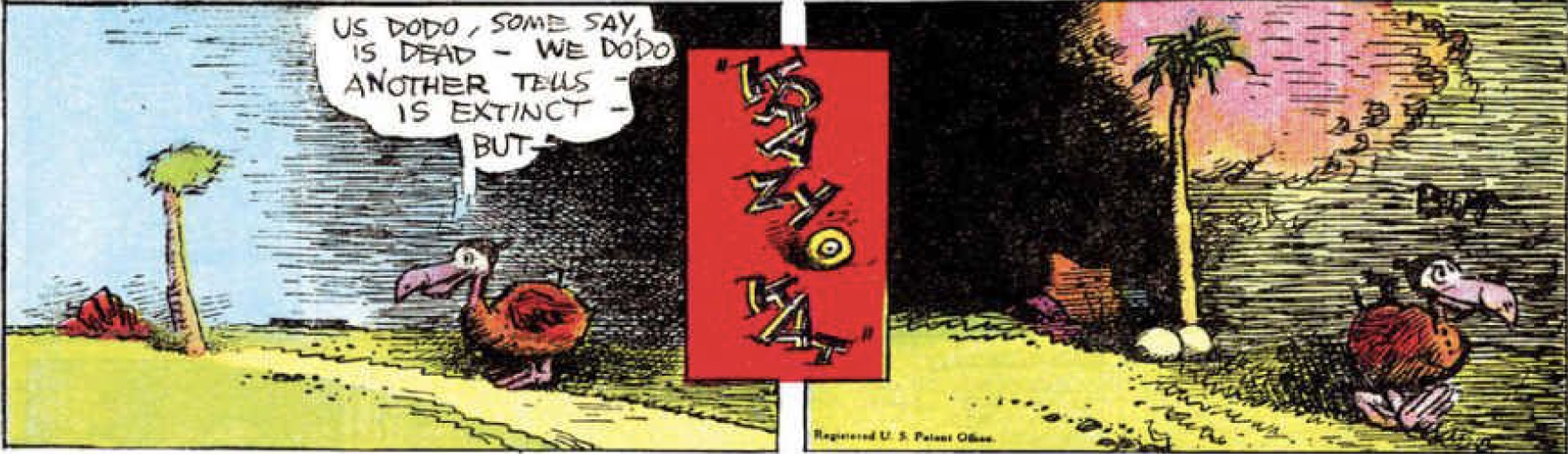

Us dodo

William supported the artist as his illness took hold. Without William’s assistance, Herriman’s illness, non-alcoholic cirrhosis of the liver, took hold and his health declined. Survival was on his mind. Earlier that year, the Sunday strip on April 11 opened with a dodo bird eying a nearby tree. Speaking to us, the readers, she remarks that “Us dodo, some say, is dead—we dodo another tells—is extinct—But …” In the following frame, the bird walks away with a determined look, leaving two large eggs at the foot of the tree.

A few frames on, just before Ignatz has time to seize them, they hatch, crying “Us dodo, we now enter a life of sweet extinction.” Brimming with energy in their paradoxical state of being/non-being, they set off in pursuit of the confused mouse.

Like Herriman, the dodo defies logic: It is meant to be dead but persists. Like Herriman, the dodo is an enigmatic bird; many doubted its existence in history and there is not much evidence to construct a reliable biography.

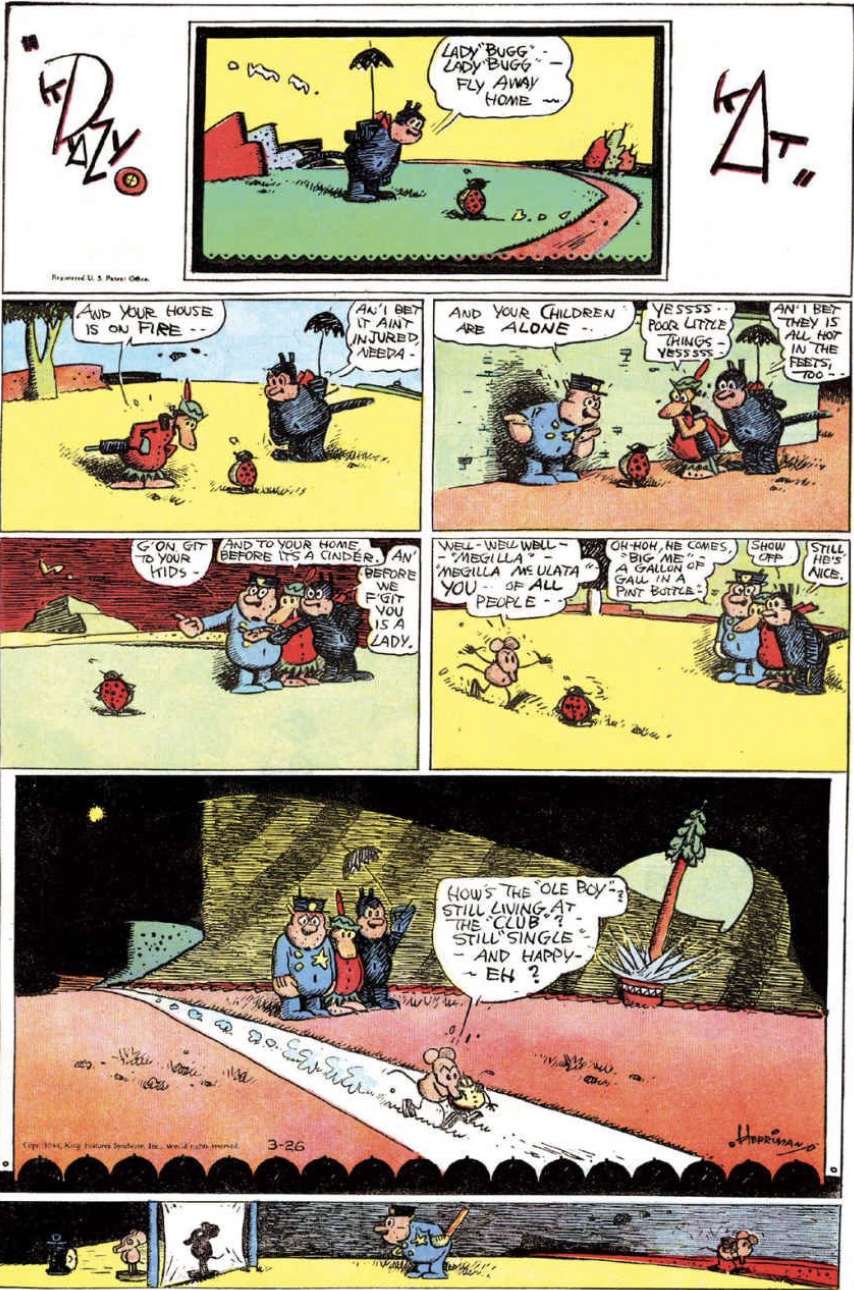

Given Herriman’s terminal condition and the apocalyptic backdrop of the second world war, the Krazy strip is strewn with references to impending doom. These references, though, are buried or veiled, like so much of the artist’s life, leaving readers with tantalising clues that could as easily be red herrings. In March 1944, just a month before the artist’s death, a Krazy Kat Sunday strip signals catastrophe but is so lightly delineated that any reading of it remains speculative. It opens with Krazy addressing a ladybird, reciting a well-known children’s nursery rhyme:

“Ladybird, ladybird fly away home,

Your house is on fire and your children are gone,

Your house is on fire,

Your children shall burn!”

Herriman softens the last line, rendering it as “And your children are alone” but the overall impact is foreboding and doom-laden. The verse is said to have been recited by farmers attempting to save ladybirds before they set alight their stubble fields after harvest. The act of grace was in gratitude to the insects who protect plants against destructive pests and who would have remained amid the stubble. Still, the rhyme stresses catastrophe and the cast of the strip deliver it like a street gang:

“Offissa Pupp: Go on git to your kids.

Mrs Kwak Wakk Duck: And to your home before it’s a cinder.

Krazy Kat: And before we f’git you is a lady.”

This is atypically callous for these characters, who are generally on the side of good. Equally uncharacteristic is the ladybird’s rescue from the situation by Ignatz the mouse, more usually Herriman’s rogue. Here, he swoops in, flamboyantly greeting the ladybird, throwing a friendly arm around it and steering it away from the gang. He calls the insect by its more formal name—Megilla McUlata, a Herriman mutation of the scientific nomenclature ‘megilla maculata’—and asks after the “ole boy.”4

It’s an odd scene and not easily written off as a comedic episode; however, it offers clues to something deeper. The evocation of “megilla” might be more than scientific precision. The word is derived from the Hebrew Megillah, which is best known in the Jewish religion as the scroll of Esther, chanted in the synagogue on the eve of Purim and again the following morning. The festival of Purim celebrates the deliverance of the Jews from destruction in the 5th century BC, when the Persian King Ahasuerus is persuaded by his Queen, Esther, to help them. Unknown to her husband, Esther was Jewish, a ‘passing’ that Herriman would recognise.5 The festival of Purim is celebrated in March (in 1944, it was March 8 and 9) and Herriman’s strip was published on Sunday, March 26 of that year.

The scale of the ongoing Holocaust was already known to the American public for at least a year. In Illinois, for instance, A. A. Freedlander of The Sentinel, published an editorial on March 18, 1943, marking that year’s Purim:

“All realise that there cannot be the customary unrestrained Purim merriment when, as at present, millions of Jews in Europe are not merely threatened with but undergoing actual extermination and the most sinister and savage anti-Semite of all time goes on exacting his toll of innocent Jewish life with seeming impunity ...

When Hitler is gone we shall celebrate another Purim in commemoration of his defeat, but let it be our last such festival, for we shall no longer be the defenseless, homeless, helpless folk whose very weakness invited attack.”

Herriman, already contemplating his own extinction while embedding his work on a daily basis in the great clock of Hearst’s empire, may have widened his sights to consider the genocidal elements of the war around him.

It may seem tenuous to argue that a reference to the Holocaust was embedded in a Sunday newspaper comic strip, but to follow that thread, it would be logical for Herriman to turn to the fable as a traditional moral vehicle and, more precisely, refer to the work of Mark Twain, who published “Some Learned Fables for Good Old Boys and Girls” in 1875.

A short story, Twain’s “Fables” recounts how some time in the future the animals of the woods send out an expedition to the unexplored world where they discover a book which states: “In truth it is believed by many that the lower animals reason and talk together.”

When the great official report of the expedition appeared, the above sentence bore this comment: “Then there are lower animals than Man! This remarkable passage can mean nothing else. Man himself is extinct, but they may still exist. What can they be? Where do they inhabit?”

Twain wrote this story while working on The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and human extinction was on his mind. In one famous section of that novel, Tom Sawyer and his friends run away and hide on a nearby island in the river. Waking after his first night abroad Tom gradually takes in the natural scene around him: worms, ants, and then a ladybird:

“A brown-spotted ladybug climbed the dizzy height of a grass blade, and Tom bent down close to it and said, ‘Ladybug, ladybug, fly away home, your house is on fire, your children’s alone,’ and she took wing and went off to see about it—which did not surprise the boy, for he knew of old that this insect was credulous about conflagrations, and he had practiced upon its simplicity more than once.”

Tom and his friends are feared dead by their townspeople and having woken up properly they watch strange activities unfolding on the river:

“’That’s it!’ said Huck; ‘they done that last summer, when Bill Turner got drownded; they shoot a cannon over the water, and that makes him come up to the top. Yes, and they take loaves of bread and put quicksilver in ‘em and set ’em afloat, and wherever there’s anybody that’s drownded, they’ll float right there and stop.’...

‘By jings, I wish I was over there, now,’ said Joe.

‘I do too,’ said Huck. ‘I’d give heaps to know who it is.’

The boys still listened and watched. Presently a revealing thought flashed through Tom’s mind, and he exclaimed:

‘Boys, I know who’s drownded—it’s us!’”

By March, when this strip was published, Herriman had a month left to live and in a letter to a friend it’s clear he sensed extinction:

“I’ve sure been

a pretty sick dodo—

In the

Hospital

most of the

time

Dropsy—and a Bad Liver that’s

going to get me

me the rope

some day.”

He died in his sleep on April 25, 1944 and his character, Krazy Kat, died by drowning in June when the paper published his final strip.6

Francis McKee is an Irish writer and curator based in Glasgow. His most recent books include How to Know What’s Really Happening (2017), Even the Dead Rise Up (2018), and Dark Tales (2019). McKee is a lecturer in the MFA program at Glasgow School of Art and the director of the citu’s Centre for Contemporary Art.

Read next: Imaginary Dinner Party, Part Eight by Lynn Crawford

Endnotes

1. Krazy Kat’s gender and sexuality is a controversial subject. From the beginning, the cat was referred to by Herriman as both “he” and “she” to the consternation of some readers. As a young man, the film director, Frank Capra, met Herriman and records a conversation he had with Herriman:

“I asked him if Krazy Kat was a he or a she,” he writes. Herriman, Capra tells us, lit his pipe before answering. “I get dozens of letters asking me the same question,” Herriman told Capra. “I don’t know. I fooled around with it once; began to think the Kat is a girl—even drew up some strips with her being pregnant. It wasn’t the Kat any longer; too much concerned with her own problems—like a soap opera. . . . Then I realized Krazy was something like a sprite, an elf,” he continued, according to Capra. “They have no sex. So the Kat can’t be a he or a she. The Kat’s a spirit—a pixie—free to butt into anything.” Capra, bemused by the answer, remarked, “If there’s any pixie around here, he’s smoking a pipe.” Capra sounds sceptical of Herriman’s explanation: it sounds disingenuous, with the artist deflecting the issue.

It may be slyer than that, though. Recent research on sexuality between the 1900s and the mid-1930s has revealed an openness on questions of gender and sexuality that challenges traditional notions around the visibility. In Gay New York (1994) George Chauncy argues at the turn of the century there was an emerging social group self-identifying as “fairies” and that doctors and gay intellectuals were conceptualising “fairies” (as well as lesbians or ‘lady lovers”) as a “third sex” or an “intermediate sex” between men and women, rather than as men or women who were also “homosexuals.”’ Chad Heap’s Slumming (2009) and William J Mann’s Wisecracker (1998) flesh out the history of this time). There is also evidence that Herriman’s readers felt that Krazy represented something more than a “sprite.” The Krazy Kat Club established in 1919 by Cleon “Throck” Throckmorton had a sign with a Herriman-styled cat being hit by a brick and a motto over the door read “All soap abandon ye who enter here.” A back-alley speakeasy, the club quickly became known for its openness to customers of all sexual persuasions. It became a focus for hot jazz in the city and may have inspired the 1928 hit, “Krazy Kat” by the Frankie Trumbauer’s Orchestra and Bix Beiderbecke.

Later again, the Beats would claim kinship with Krazy Kat: Jack Kerouac linked “the inky ditties of old cartoons (Krazy Kat with the irrational brick)” to “the glee of America, the honesty of America.” The hippie underground built on this, re-establishing the work of Herriman (described by Robert Crumb as the “Leonardo da Vinci of comics”) via reprints such as the Real Free Press Krazy Kat Komix in Amsterdam. This interest, the revelation of his passing by Ishmael Reed, and the Kat’s androgyny all combined to propel Krazy into a new sphere of relevance.

2. John Woodrow Cox, The Washington Post, June 23, 2017

3. Michael Tisserand, George Herriman: A Life in Black and White, Harper Perennial, 2016, page 417

4. Ignatz is considered to be Jewish by many readers of Krazy Kat. Sarah Boxer, for instance, in The New York Review notes: “And Ignatz, the l’il skeptic who doesn’t believe in Santa Claus and whose sons are named Milton, Marshall, and Irving, is, I’d guess, Jewish. (Never mind that Ignatz is not a Jewish name and that he occasionally marches around in a kind of Klansman’s garb; Krazy does too.)” June 14, 2007.

5. There is a final long frame at the bottom of Herriman’s Sunday strips in this period which were designed to hold banner advertising. Krazy Kat was not a popular choice for such ads as it was considered too dense and complicated by many. Herriman filled the frame with one-off images that obliquely referred to the strip above, rather like an emblem where one image enigmatically critiques another. In the ladybird strip the final frame presents us with Offissa Pupp entranced by a projection of Ignatz while the real mouse passes unnoticed behind him.

6. In the final long frame, following the image of a drowned Krazy, we see Krazy floating happily on water, holding a small makeshift sail. We may be clutching at straws to believe this is a sign of survival or perhaps one last assertion of the cyclical nature of the universe.